Tombstones in the shape of churches.

By Sam Topalidis 2016

1. Introduction

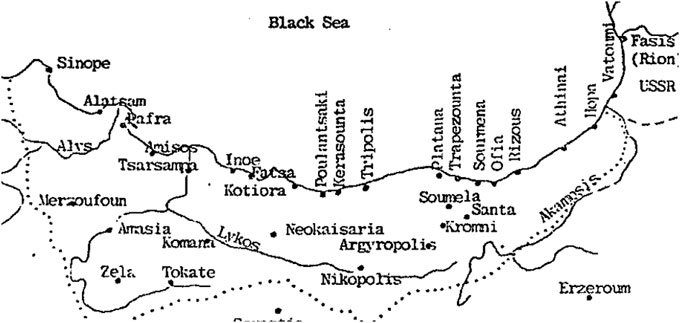

There is a lack of written culture in English about Pontos, the northeastern region of Turkey adjacent the Black Sea (See Figure 1). This is especially true on orthodox christian Greek funeral rituals. This article addresses this issue with descriptions of Greek funeral rituals primarily from the villages of Santa 66 km (by road) south of Trabzon (which were applicable to many other areas in Pontos) and for crypto-christians in the villages of Kromni 70 km (by road) south of Trabzon (spelt Trapezounta in Figure 1). (See Note 1 on crypto-christians.)

The christian Greek refugees from Pontos (Pontic Greeks) brought a rich cultural heritage with them in the early 20th century when they were forced to leave their homeland and settle in Greece.

2. Funerals in Santa

The following section relies heavily on the work of S. Papadopoulos (1983) with minor alteration whose sources were Greek articles by Lianidis (1964), D Papadopoulos (1956), Ioannides (1981) and Papananiades (1958) which he translated into English. Lianidis (1964) provides the following description of funerals in Santa which is essentially the same description as the other articles S. Papadopoulos (1983) studied. (See Note 2 on Santa and nearby Kromni.)

There were superstitious beliefs that when someone dreamed of losing a tooth, a relative would die. Owls on top of a house would be chased away, because they were believed to be the messenger of death. A howling dog was another superstitious belief that someone was going to die and would also be chased away. Death was also predicted when a chicken would crow like a rooster. In this instance the chicken would be slaughtered.

Figure 1 Santa and Kromni in Pontos (S. Papadopoulos 1983, p. 248)

When a person who was very ill realised that their death was near would call their relatives to give them their blessings. They would also tell their relatives their wishes and the relatives would kiss the hand of the dying person.

It was considered a sin for the dying person not to receive communion. When a priest was not available to deliver communion, the dying person was provided with holy water which was kept by the family’s icons.

When death was near, people would stop crying to avoid scaring the dying person so their soul would not leave the body. If, during the expiring period the body made certain moves, it was believed the dying person had seen the angel who came to take their soul. When a person died peacefully, it was believed they had a very good heart. When a person had a difficult death, it was believed their parents had placed a curse on them or in some cases that the person was expecting a relative to arrive from abroad.

S. Papadopoulos (1983) describes when his own paternal Pontic Greek grandmother was dying she kept asking for his father. When a picture of his father was placed on her she then died. The practice of placing a picture or other items that belonged to the individual the dying person was asking for was very common in Pontos.

Itinerant merchants and migrant workers ran a risk of dying away from their blood relatives. Pontic Greeks believed that a soul could be in jeopardy if blood relatives were not present at the death, although having an article of clothing belonging to a relative of the dying person was an adequate substitute (Lianidis (1964) in Doumanis (2013)).

Shortly after a person died, the church bell would be rung. (See Note 3.) The villagers would stop working and go to the house of the deceased to pay their respects. And thus, the house of the deceased would fill with people. Young children living in the house were sent to a relative’s house. Someone would empty the water containers in the house, as it was believed that the angel of death washed his swords in them prior to his departure from the household.

The deceased would have their eyes and mouth closed, legs straightened and their hands crossed. The body was then washed and wrapped in a shroud. [Tanimanidis (1988) also states in Pontos (no specific area was mentioned) that the deceased also had their nails clipped and had an icon placed in their crossed arms.] Older Pontic Greeks usually prepared in advance the clothes to be worn by the deceased for burial. Like Greek orthodox religious practices, cremating bodies was not allowed.

It was common practice for Greeks to dress their dead in their best clothes, preferably in clothes that had not been worn (Politis (1931) in Varvounis (2015)). In Ordu (spelt Kotiora in Figure 1) 180 km (by road) west of Trabzon, Pontic Greeks usually adorned their dead richly, especially the wealthy (Akoglous (1939) in Varvounis (2015)).

Once the deceased was dressed, the body was placed in bed, until a casket, which was prepared free of charge by a carpenter, was prepared. A piece of black material was placed on top of the casket when the deceased was old. Material of different colours was placed on the casket when the deceased was young. If the deceased was a priest he was not placed in a casket, but seated in a chair made especially for the purpose.

Relatives would dress in black and sit around the deceased with the mother of the deceased sitting by the head. If the deceased had no surviving mother, the spouse would sit by the deceased’s head. The body remained in the house for 24 hours. Many people would stay up all night with the deceased. The cats were chased out of the house because it was believed if the cat attacked the deceased, the deceased would become a ghost. It was also believed that the devil was disguised as a cat to attempt to enter the dead body.

When the time came to take the deceased, the priest entered the house with a chanter and other individuals. The women would then begin wailing. As soon as the body was carried away in the casket filled with wild flowers, with a pillow placed under the deceased’s head, the doors and windows of the house were opened to allow Charon [the Greek mythological ferryman of the underworld who carries souls of the newly deceased to the world of the dead] to escape so no one else in the house would die.

When a young child died, the mother was not allowed to participate in the funeral. It was believed that her other children would also die if she were to do so. When the deceased was transported to and from the church, the other houses in the village would shut their doors and windows. The procession to and from the church was formed as follows:

- In front was the man who carried the top of the casket

- Followed by someone carrying kollyva (a tray full of special boiled wheat)

- Someone carrying the cross

- The chanter

- The priest

- The people carrying the deceased in the casket

- Relatives of the deceased

- And finally the other villagers.

If the procession passed a relative’s house, the casket would be put down and the priest would say a prayer. [Tanimanidis (1988) states that in Pontos (but no specific area was mentioned) on the way to the burial, a lit candle which was placed in flour or wheat was carried close to the deceased’s head. A lit incense burner was also carried close to the deceased’s head. Also laments were spoken or sung which often mentioned an after-life and would refer to their loved ones who had already died.] After the burial service in church, the procession would continue to the grave which was dug by volunteers. The casket was placed in the grave, and the priest would say another prayer. Here the volunteer undertaker would take the pillow from under the head of the deceased and replace it with a pillow made out of dirt. He would also cut off a piece of the shroud which would be burnt if someone attending the funeral became ill for no apparent reason.

The priest was the first to throw dirt on the casket, then others followed. Sometimes items were placed in the grave which the deceased was fond of, e.g. toys for children, worry beads for older men and spindles for older ladies. Once the grave was covered, the shovel and the pickaxe used to dig the grave were placed on top, forming the shape of a cross and left there for three days. After the burial, drinks and the kollyva were distributed to the mourners. It was also customary for relatives to light a candle on top of the grave for 40 days. [In the Greek orthodox religion it is believed that on the 40th day the soul may ascend into heaven.]

It was observed that peculiar to the Kromni-Stavri district, christian Greek tombstones were carved in the shape of a foreshortened church less than 1 metre high. Some had conical tops, barrel-vaults, ogival doorways like mihrabs (Plate 1) (Ballance et al. 1966). Popov (2003) observed the oldest Pontic Greek tombs in northwestern Caucasus were cut from stone sometimes in the shape of miniature orthodox churches and they usually had special niches for candles. These first tombs were dated to the end of the 19th century, so this style was brought from the Pontos, [probably from the Kromni-Stavri district].

Plate 1 Stavri tombstones in the shape of churches (Ballance et al. 1966, p. 294)

Although the funeral processions in various parts of Pontos were basically the same, different superstitions relating to death existed in different parts. Papananiades (1958) reports in Samsun (Amisos), 330 km (by road) west of Trabzon (Figure 1), when the face of the deceased was sulky; it was believed that another family member was also going to die. In the past, when a person died, a coin was placed under their tongue [to pay Charon for the ferry ride to the underworld]. This was modified by having the priest place two candles forming a cross on top of the mouth of the deceased. If a cat came by the grave during the burial service this was considered a bad omen. It was a sign that the dead body would not dissolve. It would dissolve only if the cat was caught, and holding it, it was forced to go around the grave seven times.

Memorial services were customary and were held on the third day, ninth day, 40th day and one year after the individual’s death. (See Note 4.) On each of these occasions a tray was filled with kollyva and decorated with sugar, nuts, raisins and pomegranate seeds. In the middle of the kollyva was formed the sign of a cross and at the bottom of the cross the initials of the individual to be commemorated were written. This tray was then carried to the church and after it was blessed, distributed to people who attended the church service.

Mourning in Pontos was as follows. Shortly after a person died, women dressed in black. Male relatives did not shave or cut their hair for at least 40 days. No celebrations were attended and women would take down house decorations. During the first few days after the funeral, those in mourning would not come out of their homes.

3. Crypto-christian funeral rituals in Kromni

Andreadis (2007) provides the following information on crypto-christian funeral rituals in the villages of Kromni as described to him by his grandmother (born 1867 and died 1955) who was raised in Kromni.

The crypto-christians held their funerals after dark in their house chapels. In the countryside, people were allowed to bury their dead on their own property, so in Kromni, the crypto-christians were buried with orthodox christian rights in their own gardens. Muslim outsiders never saw the burial services.

In larger towns, however, the crypto-christian (the ‘supposed muslim’) had to be buried in the muslim cemetery. In the Muslim community there were specialists who prepared the muslim body for burial and it would have been suspicious if a muslim (or crypto-christian) family did not call them to follow muslim burial practices. As part of the burial service, muslims wash their dead in extremely hot water, hotter than anyone living could bear. This was an issue for crypto-christian men because of the muslim tradition to circumcise their young boys [which was not a tradition for christian Greeks]. (See Note 5.) Instead, the crypto-christians in the towns often used an alternative muslim funeral custom; when immediately after death they sewed the body into a white shroud which was not opened again. Instead of a funeral casket, the deceased was placed upon a wooden bier and taken to the porch of the mosque, where it was positioned with only the feet in the entryway. They recited the prayers and verses from the Koran and then buried the shrouded body directly into the grave.

Hortlak

Andreadis (2007) describes a prejudice after death called Hortlak (ghost) in Kromni which was also told to him by his grandmother. This prejudice was specifically nurtured toward the end of the 19th century, when the number of professed christians rose as the crypto-christians began to reveal themselves as christians.

The people of Kromni believed that a dead person, regardless of religion, who left debts, could not rest in peace until their debts were paid. Until these debts were paid the Hortlak came out of the grave at night crying and shouting. After the debt was settled the christian priest would perform a small service or read prayers over the grave. [It appears interesting that most Hortlaks were muslim.]

4. Conclusion

It is hoped the collation of these christian Greek funeral rituals from Pontos will help disseminate this information to those who cannot read Greek. Such rich Pontic Greek culture should not be forgotten.

5. Notes

Note 1: The following link lists my articles on the excellent Pontic website Pontosworld, which include those on the crypto-christians in the Trabzon region who were christians and secretly upheld their Greek language, customs and christian beliefs at home but who publicly declared themselves as muslims: https://www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis

Note 2: According to Bryer (1968, p. 113) in 1857 there were 615 families in the eight villages that comprised Santa. With an approximate figure of five people per household this equates to about 3,075 people. Ballance et al. (1966, p. 272) using acting British vice-consul Steven’s figures in his 1857 report, claimed in the nine villages in the Kromni-Imera region there were 808 christian, 370 crypto-christian and two muslim families. Using five people per family this equated to 4,040 christians, 1,850 crypto-christians and 10 muslims. The christian and crypto-christian numbers appear high.

Note 3: Fotiadis (2001, pp. 369–70), states that after the Hatt-i-Hümayun (1856), the Ottoman sultan allowed christians to build christian churches and celebrate christian rites and traditions. However, the christian churches could only be built if approved by the Ottoman Government in Constantinople. The repair of old christian churches was also allowed, but in areas where there were muslims, christian celebrations were not allowed in public. Bells were allowed to be rung in areas where mostly christians lived.

Note 4: Rice (1967) states that in Byzantine times the Byzantine emperor wore white when in mourning while all others wore black. On the third, ninth and 40th days after burial (the intervals prescribed by Babylonian astrologers who based their calculations on the lunar cycle), the family would gather around the tomb to recite laments.

Note 5: Andreadis (2007) believes male crypto-christians were sometimes circumcised. In communities where it was impossible to escape the scrutiny of muslim neighbours, a male crypto-christian child would be secretly baptised and at the appropriate age also undergo muslim circumcision so as not to arouse suspicion.

6. Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the work of Dr Steve Papadopoulos, a proud Pontic Greek, whose 1983 thesis was used in this article. I warmly thank my cousin John Papadopoulos for translating excerpts from Fotiadis (2001) which were also used here. I also warmly thank Aris Tsilfidis in translating Tanimanidis (1988) for me and for his on-going support in fostering Pontic culture and history. To all the above Temeteron.

My aim is to write well-researched articles on Pontic history and culture in English to spread this knowledge to those who cannot read Greek sources.

7. References

Akoglous, X 1939, Laografica Kotyron, (in Greek), [On the Folklore of Kotyora (Ordu)], Athens, Greece.

Andreadis, G 2007, ‘Faith unseen: the crypto-christians of Pontus, part 1’, Road to Emmaus, vol. viii, no. 4, pp. 2–53.

Ballance, S, Bryer, A & Winfield, D 1966, ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes – Part 1’, Archeion Pontou, [Archives of Pontos], vol. 28, pp. 234–305.

Bryer, A 1968, ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes – Part 2’, Archeion Pontou, [Archives of Pontos], vol. 29, pp. 89–129.

Doumanis, N 2013, Before the nation: Muslim-christian coexistence and its destruction in late Ottoman Anatolia, Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Fotiadis, K 2001, The forced islamization in Asia Minor and the crypto-christians in Pontos (in Greek), Kiriakidis Bros, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Ioannides, A 1981, ‘I kidies ke ta mnimosina sta horia tou Pontou’ (in Greek), [‘Funerals and memorial services in villages of Pontos’], Pontiaki Estia [Pontic Hearth], vol. 41, pp. 359–60, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Lianidis, S 1964, ‘Nekrika kai tafika sti Santa tou Pontou’ (in Greek), [‘Rituals during funerals and burials in Santa in Pontos’], Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], vol. 26, pp. 159–76.

Papadopoulos, DK 1956, ‘Ethima ke doxasie tou hioriou Stavrin’ (in Greek), [‘Customs and beliefs of the village Stavri’], Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], vol. 21, pp. 102–21.

Papadopoulos, S 1983, Events and cultural characteristics regarding the Pontian-Greeks and their descendants, PhD thesis, School of Education, Health, Nursing and Arts Professions, New York University, New York.

Papananiades, E 1958, ‘Ethima, doksasie, prolipsis ke disidemonie Amisou ke alon meron’ (in Greek), [‘Customs, beliefs, superstitions and preventing superstitions in Amisos (Samsun) and other places’], Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], vol. 22, pp. 244–60.

Politis, NG 1931, ‘Ta kata tin televtin’ (in Greek) [‘Customs and practices around the demise’], Laografika Symmeikta [Folklore Melanges], vol. 3, Publications of the Academy of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Popov, A 2003, ‘Becoming Pontic: post-socialist identities, transnational geography, and the native land of the Caucasian Greeks’, Ab Imperio, vol. 2, pp. 339–60.

Rice, TT 1967, Everyday life in Byzantium, Dorset Press, New York.

Tanimanidis, P 1988, ‘Kitheies kai mnimosina’ (in Greek), [‘Funerals and memorials’], in Enkyklopaideia Pontiakou Ellinismou [Encyclopaedia of Greeks from Pontos], vol. 2, Malliaris Education, Thessaloniki, Greece, pp. 210–2.

Varvounis, MG 2015, ‘Death costume and ritual lament in Greek folk tradition (19th – 20th century)’, Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 299–317.