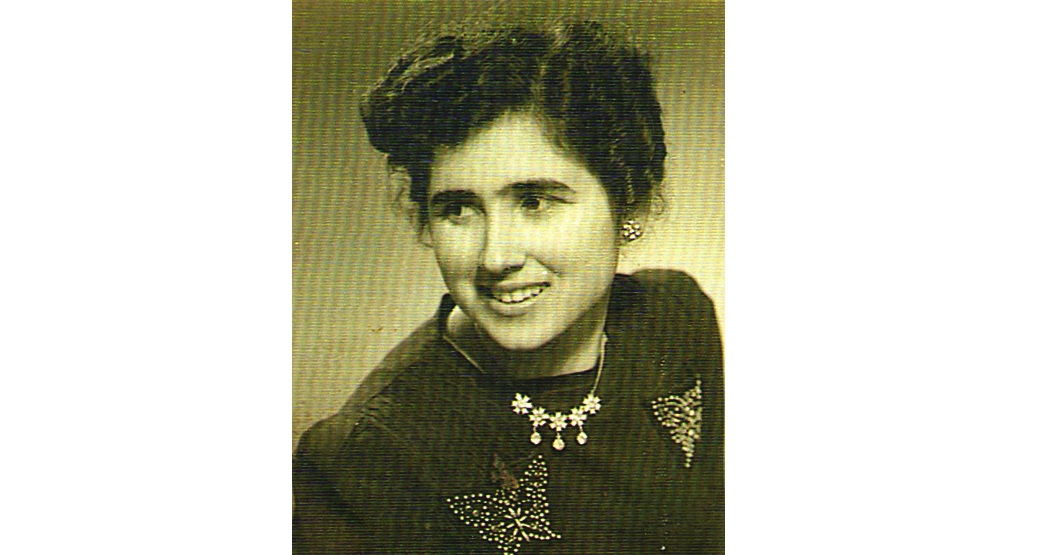

Plate 1: Sofia Spyridopoulou (1950s) (family photo)

By Sam Topalidis, Pontic historian.

(updated 2022).

Introduction

This family history of Sofia (Spyridopoulou) Dimarhos (Plate 1) documents oral history from Sofia, some of which was passed down to her from her mother, Maria. I have enhanced this oral history with published historical information located predominantly in the Notes section.

Sofia’s family history tragically reminds us of the hardships endured by Pontic Greeks1 from the north-east portion of Turkey (Pontos) at the hands of the Ottoman Turks and the Kemalists in the early 20th century. May we remember their struggle for survival.

Sofia Dimarhos

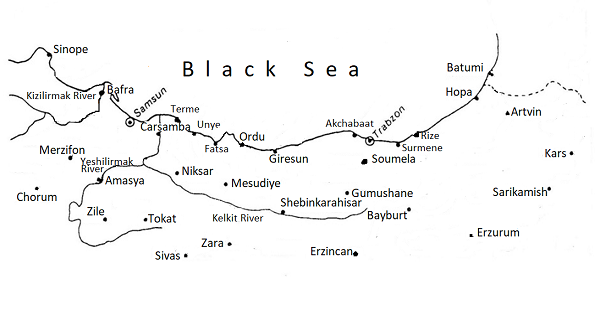

Sofia was born Sofia Spyridopoulou in 1934 in Veria, northern Greece. In 1935 her family moved to nearby Katerini. Her older half-sister Maria was born in 1928, also in Veria and she died in Sydney, Australia in 2009. Sofia also had two brothers, Elias and George. Elias died in Canberra, Australia in 2015 and George lives in the USA.

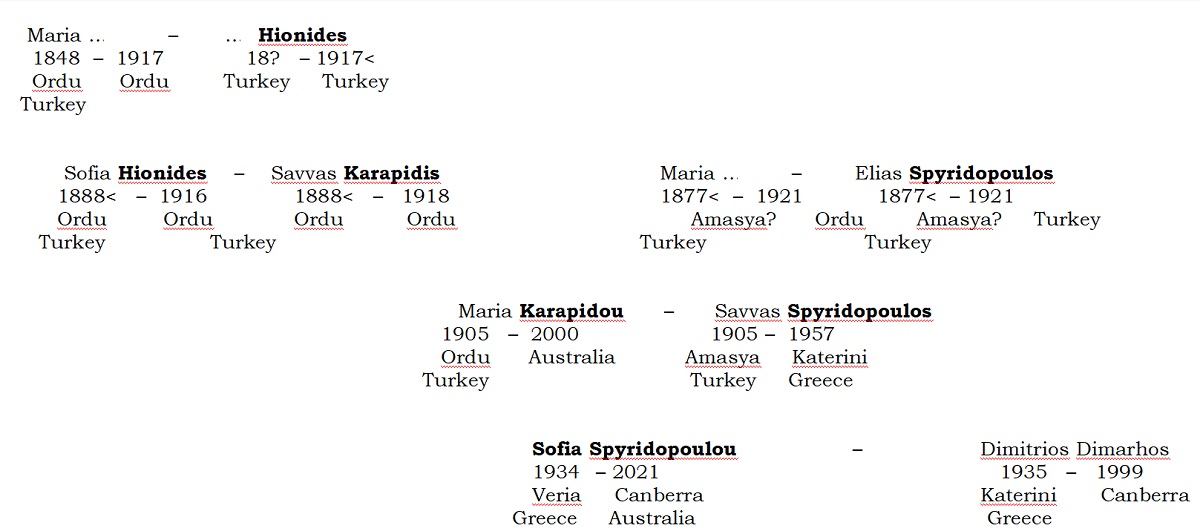

Sofia moved to Australia in 1961. In 1962, her fiancé, Dimitrios Dimarhos, also emigrated to Australia and they married in Sydney that same year. In 1977, the family moved to Canberra. Dimitrios was born in Katerini and his father was a Pontic Greek from the Caucasus (where many Pontic Greeks lived) but his roots were from Trabzon (Figure 1). Dimitrios’ mother was born in Pontos. When Dimitrios’ father moved from the Caucasus to Greece (before 1935) he changed his name from Dimarhopoulos to Dimarhos. Dimitrios died in 1999 in Canberra. Sofia died in 2021 in Canberra. Sofia had three children: Theo, Savvas and Angela and many grandchildren.

Sofia’s Ancestors

Sofia’s father, Savvas Spyridopoulos, was born in 1905 in the picturesque in-land town of Amasya (Figures 1, 2) but his family must have moved soon after his birth to Ordu. The town of Amasya is on the Yeşilirmak River, 180 km (straight line distance) south-west from Ordu. Savvas died in 1957 in Katerini.

Figure 1: Settlements in north-eastern Anatolia (Pontos) (scale: 290 km from Samsun to Trabzon)

Sofia’s mother, Maria Karapidou, was born in 1905 in Ordu (Kotyora, Note 1) and died in 2000 in Sydney, Australia. Interestingly, Sofia’s mother’s religion and most probably that of her mother before her was Protestant, not Greek Orthodox. (Note 2.)

Sofia’s mother’s father, Savvas Karapidis, was also born on Ordu sometime before 1888 (Figure 2). Savva’s occupation was tin-plating copper utensils thus making them safe for kitchen use. His family lived in a two storey house decorated with Persian carpets. He also owned a house at Tsampasin, the summer village (parhar), 50 km south of Ordu at over 1,800 m elevation. Savvas worked away from Ordu for six months of the year (which included the unpleasant summer) and travelled as far away as Bulgaria applying his skills.

He was forced to join the first exodus of Greeks from Ordu in 1917. He survived this exodus (death march) and returned to Ordu which must have been after the end of World War I for the Ottomans (i.e. after 30 October 1918). When he returned, the Turks who occupied his house had removed several doors and used them as firewood. His children did not go on the exodus but they were evicted from their house. Fortunately they were fed and housed by neighbouring Turks. However, literally two days after Savvas returned home in 1918 he died.

Sofia’s mother’s mother, Sofia Hionides, was also born in Ordu before 1888 and died in 1916. During the four warmest months of each year she took her children to their reasonably large house 50 km south at Tsampasin. Sofia Hionides’ husband did not travel to Tsampasin as he was working overseas. When it was time to leave for Tsampasin a Turk was hired to cart the family there with household items and food. In Tsampasin they did not have livestock nor did they grow any crops. The family must have lived a relatively comfortable life.

Sofia Hionides’ brother was Ioannis (1875–1922), father of Dr Constantinos Hionides, author of Pontic history.2 The story goes that Ioannis was so pale and his hair so white that he was called Hionides (son of snow). Ioannis was also called Hadjiyiannis because on his return to Ordu (before 1914) from South Africa, he visited the holy tomb (Ayios Tafos) in Jerusalem.3 (He had not been on the Haj to Mecca.)

In July 1914, Ioannis was conscripted into the Ottoman army. (In early 1915, Christians were not allowed to bear arms in the Ottoman army and were conscripted into the dreaded labour battalions attached to the Ottoman army carrying supplies and building roads. Many Greeks died in terrible conditions in these battalions.) Fortunately Ioannis deserted from the labour battalion and went into hiding in Ordu. In August 1917, he boarded one of the Russian ships from Ordu and ended up at Batum on the Black sea coast (Figure 1). (Note 3.) In 1920, he returned to Ordu. In August 1921, the Turks forced Ioannis to join one of the groups in the second Greek exodus from Ordu. This was a death march into the interior of Anatolia. Ioannis tragically froze to death in 1922 while working on the road near Bitlis (southeast corner of Anatolia). His name was written on the back of his shirt (to help identify his body).3

Figure 2. Sofia (Spyridopoulou) Dimarhos’ ancestors

In 1915, Sofia’s mother (aged 10 years old) witnessed Armenians; mostly children who were tied together being marched by Turks near her house in Ordu. They were in a hungry and dirty state. Sofia’s grandmother told Sofia’s mother, ‘don’t go to the Armenian homes and steal any of their items, I don’t want to have any stolen goods’. We know now these Armenians were being marched to their deaths in what is called worldwide as the Armenian Genocide.4

Sofia’s great-grandmother, Maria Hionides (Figure 2) was born in 1848. In the last 15 years of her life, Maria was blind. She did not escape in 1917 from Ordu on the Russian ships. (Note 3.) However, soon after the Russian ships departed, the Turks drowned her in the Black Sea.5

Sofia’s mother, Maria, remembered that the Turk, Topal Osman, sent a telegram to the Mayor of Ordu (a family friend) stating he wanted to come to Ordu to ‘clean-up’ [murder] the Greeks. The telegram was responded with words to the effect, ‘if the Greeks need to be cleaned-up in Ordu, I will do it myself’. The threat of Topal Osman and his band of ‘cut-throats’ would have been horrifying news to the Pontic Greeks, as Osman’s record of murdering Greeks was well known. Topal Osman did indeed enter Ordu in December 1920 and in February 1922 with a band of Turkolazes and inflicted damage and murder in the town.

Sofia’s mother’s parents had died by the time Sofia’s mother, Maria Karapidou, (aged 17 years), was forced in late 1922 to leave Ordu destined for Greece. Maria left Ordu by ship with her two younger brothers and her older sister. Tragically there were many other orphaned children on board.

Sofia’s mother, Maria from 1941

In 1941, during the German occupation of Greece in World War II, the Germans imprisoned Sofia’s mother, Maria. She was imprisoned for months in Thessaloniki for hiding two New Zealand soldiers. The Germans could not gaol Sofia’s father as he was in hiding. Soon after Maria’s release the Germans arrested her again and gaoled her for a few more months.

In 1952, a Pontic Greek family friend, Lazaros Anamatidis, returned to Ordu on a holiday. In Ordu, Lazaros encountered the Turk who had saved Sofia’s father from the 1921 Greek exodus. The Turk gave Lazaros a letter asking Savvas to visit him in Ordu. (A friend translated the letter. So I assume it was Ottoman Turkish written in the Arabic script.) And so, in September 1953, 31 years after leaving Pontos, Savvas visited the Turk in Ordu, disregarding his family’s concern for his safety. He stayed with the Turk until late November 1953. Savvas returned to Greece and died in 1957. What a touching story.

In 1971, Sofia’s mother, Maria, moved to Sydney, Australia to live with Sofia’s family. In 1977, the family moved to Canberra. Years later, Maria travelled between Canberra and Sydney living with relatives. Even though Maria was in poor health for periods of her life, she lived till the ripe old age of 95 years. She died in 2000.

Sofia’s Husband Savvas

Sofia’s father’s mother, Maria was born in either Amasya or Ordu and had died in Ordu in 1921, before the second Greek exodus. Sofia’s father’s father, Elias Spyridopoulos who was probably born in Amasya, had died on the 1921 Greek exodus aged at least 45 years old (Figure 2). He was ill at the time of the exodus and was assisted on this forced death march by his 30 year old daughter Rothi. Sofia’s father, the then 16 year old Savvas (Rothi’s brother) was saved from this same death march by being ‘adopted’ by a Turkish friend. This Turk made a commitment that Savvas would not be converted from Greek Orthodox to Islam and he would go home when Elias returned.

This muslim Turk supported two wives and he owned a lot of a cattle. One of his wives lived in Ordu and was childless. She often wore a pistol for protection under her outer-clothing. (She was obviously someone not to mess with.) The other wife lived in a village just outside of Ordu with her children. Apparently the Turk’s children were irresponsible and Savvas, who tended the Turk’s cattle, was much loved by the Turk. In 1922, (before the survivors of the 1921 Greek exodus had returned to Ordu) the wife who lived in Ordu helped Sofia’s father to escape on a ship bound for Greece. The news of Savvas’ escape greatly upset the Turk.

On the ship bound for Greece Savvas made friends with a family who settled in Veria in northern Greece. Savvas also settled in Veria where he married one of the girls from this family. In Veria his occupation was building stocks for cattle. Unfortunately his wife died in 1931. He married Sofia’s mother Maria, in 1933 in Veria. In 1935, the family moved to Katerini, where he became a tobacco farmer, like many other Pontic Greeks. Sofia stated that in Katerini, the Greek Government gave every two refugee families from Anatolia one horse and each refugee family 29 stemmata (29,000 m2) of land.

Interestingly, around 1937, Savvas found his older sister Rothi. She had been living in Kilkis in northern Greece, but she soon moved to Katerini. Rothi had survived the 1921 Greek exodus and returned to Ordu in 1922 and then boarded a ship for Greece.

Conclusion

Sofia, was a humorous and very charming lady who was proud of her Pontic Greek roots and her family. Her family history is recorded here particularly for those with Pontic Greek heritage. ‘To know where you are going you must know from where you have been.’ Many of our Pontic ancestors were forced to walk some terrible paths from which they did not survive. It is our obligation to remember this Greek Genocide, which was perpetrated by the Ottoman Turks and then the Kemalists in the early 20th century. May we remember their struggle for survival.

1. Pontic Greeks is the academically accepted term to describe Greeks from the Pontos region of north-eastern Turkey adjacent the Black Sea.

2. Dr Constantinos Hionides was Sofia’s mother’s cousin. Constantinos was born in 1915 in Ordu and became an Andarte in Greece fighting the occupying German forces during World War II. He became a medical doctor and then migrated to the USA where he became Professor of Anaesthesiology at Boston University School of Medicine. He died in 2008. He was also a philanthropist and an author.

3. Hionides (1996). It is unknown why he travelled to South Africa.

4. The Armenian Genocide, commenced from Kerasounta (Giresun), Ordu and Samsun on 10 July 1915 (Payaslian 2009). For some first-hand accounts of the Armenian Genocide in Ordu see VK Hovannisian (2009). The human race has perpetrated some very shameful acts.

5. Hionides (1996).

Notes

Note 1

Greeks colonised Pontos from at least the 7th century BC (Topalidis 2019). According to Xenophon (ca. 400 BC) Kotyora was a Greek colony of Sinope, which itself had been founded by the Greeks from Miletos.

Kotyora does not seem to have survived the classical era and Ordu appears to have a relatively modern foundation. Its sheltered beaches are overlooked by an acropolis, Boz Tepe. The earliest reference to the name Ordu is 1813 which means ‘army’ in Turkish (Bryer and Winfield 1985). When Hamilton visited Ordu in 1836, he observed it contained 120 Greek and 100 Armenian houses; and the Turks lived in single houses or small hamlets on the hills (Hamilton, 1842).

Hewsen (2009) states, according to Cuinet (1890–1895), Ordu consisted of five quarters; three Greek, one Turkish and one Armenian. Ordu was served by three Greek churches, two mosques and one Armenian church. In late 19th century there was also a Protestant Greek and a Protestant Armenian church.

Hovannisian (2009) states the Armenians in Ordu lived on the lofty heights of Boze Tepe. The Armenian sector was situated high up on the western slopes, running into the Greek quarter below. The Turkish quarters extended easterly down to the seaside flats and government buildings and market place. Armenians made up the majority of the artisans and craftsmen and they competed with the Greeks in commerce. In the latter part of the 18th century hazelnuts were introduced into Ordu and the industry quickly flourished becoming the region’s chief export. The construction of the Ordu to Sivas road in the 1880s led to an economic boom.

Note 2

In the 19th century, Catholic and American Protestant missions were established in Pontos. The missionaries worked in important settlements on the coast and the hinterland or following existing Catholic or Protestant communities. They carried on relief work, besides their preaching duties and invested in important missing infrastructures. They also founded centres of high education presenting Christian organisations as establishments espousing western civilisation.

Due to their social involvement, especially during several humanitarian crises in eastern Anatolia, these missionaries gained a special position in Pontic society. As a result, Italian and American diplomats referred to their mission stations as an extension of their countries’ wealth, culture and international recognition. By the end of the 19th century, Protestant and Catholic missions were considered geopolitical representatives of the Great Powers and important humanitarian organisations (Kastrinakis 2008).

Note 3

The Ottoman Turks forced several ‘exoduses’ of Pontic Greeks from Ordu. After the Russians invaded northeastern Anatolia in 1916 during World War I, the Turks responded by uprooting Greeks without adequate provisions or shelter and no transportation into the interior of Anatolia starting with those closest the military front. Many Pontic Greeks perished in very harsh conditions.

The New York Times, 7 April 1918, article, ‘Bombarding Ships Rescue 2,000 Greeks’ in Kostos (2010:96) stated: a flotilla of nine warships and three torpedo boats bombarded Ordu on 9 August 1917. (The Russians had already occupied Trabzon to the east of Ordu.) The Russians aim was to clear the town of Turkish soldiers sufficiently to enter and destroy certain ammunition depots and an airplane centre. After the Russians exploded the buildings, 2,000 Greek men, women and children from Ordu’s shore were able to scramble aboard the Russian ships. They were taken to Trabzon. The story of the rescue of exiles at Ordu came to New York by two Greek refugees who were among the fortunate to escape, Lazaros George Macrides and Miss Evterpi Kantargi.

Many years ago I emailed this story to a Pontic Greek friend, Dr Ruth Macrides (who sadly has now passed away) who was an academic in England asking if she knew of Lazaros George Macrides. To my amazement, he was her grandfather!

Constantinos Hionides (Hionides 1996) was two years old when he boarded one of these Russian ships in 1917 and his family ended up in Batum. He and his family returned to Ordu in 1920.

Immediately after the Russians left Ordu in August 1917, the Turks ordered the first Greek exodus out of Ordu would occur in a matter of days. Saltsis (1995) states more than 3,000 Greeks were divided into seven groups. Every couple of days a group would depart into the Anatolian interior. Some went on the public road to Mesudiye (Figure 1). The rest went via Tsampasin to Mesudiye. From Mesudiye all the groups went on the public road Isketir, Perekketli to Niksar and finally to Erbaa (Figure 1). The distance took 30 days to travel with around 40% of the Greeks dying from hunger and disease. The elderly and the ill stayed behind in Ordu.

After 30 October 1918, at the end of World War I for the Turks, the survivors of this first Greek exodus returned to their homes. In May 1919, the Greek army landed in Smyrna on the west coast of Anatolia. A few days later on 19 May, Mustafa Kemal (later renamed Ataturk) landed in Samsun on the Black Sea coast where he planned the next round of Greek persecutions. The 19 May is commemorated by Pontic Greeks as Pontic Greek Genocide Day. In reality these massacres were part of a co-ordinated Genocide of Christians (and other minorities) in Anatolia, Thrace and other areas under Ottoman Turk control.

On 9 June 1921, a Greek warship bombed Inebolu (west of Sinope). With the perceived danger of a Greek landing in Samsun, Mustafa Kemal and his government in Ankara agreed that all Greek males aged between 15 and 50 years should be deported to the interior (Mango 2002). Thus commenced what I call the second Greek exodus from Ordu from June 1921. They were exiled from Ordu in groups. They passed inland by Tsampasin, Melet and Tivre. At Bitlis, (in south-eastern Anatolia) they stayed four months breaking rocks and building roads in winter (Hionides 1996). In June 1922, a Greek warship bombarded Samsun. This served only to worsen the lot of the remaining Greeks (Mango, 2002).

After the defeat of the Greek Army in western Anatolia in August 1922 (Greco-Turkish War, 1919–1922), Greeks were forced to leave Turkish soil. After the Greek-Turkish convention and the protocols about the exchange of Orthodox Greek and Turkish Muslim populations were signed on 30 January 1923, those Orthodox Greeks who had not left Anatolia were forced to leave. Theodore Kurtides (Kurtides (1973) in Hionides (1996)) states he left Ordu in December 1922, having been forced to leave his small town of Mesudiye about 120 km inland of Ordu (Figure 1). Some of the Greek women and children had not been exiled to the Anatolian interior but the men were still in exile. The women and children from Ordu also boarded the ships for Greece in late 1922. This can be considered the third Greek exodus from Ordu.

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank the late Sofia Dimarhos for allowing me to interview her and for her gracious hospitality. As I said to her after our interview sessions, ‘I was thin before I met you’. I also warmly thank her daughter, Angela Triandafillou for her comments to this paper.

References

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Greek Patriarchate (1919) Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey 1914–1918, Constantinople.

Hamilton WJ (1842) Researches in Asia Minor Pontus and Armenia, 1, John Murray, London.

Hewsen RH (2009) ‘Armenians on the Black Sea: the province of Trebizond’, in Hovannisian RG (ed) (2009):37–77.

Hionides C (1996) The Greek Pontians of the Black Sea, Boston.

Hovannisian RG (ed) (2009) Armenian Pontus: the Trebizond-Black Sea communities, Mazda Publishers Inc., Costa Mesa, Los Angeles.

Hovannisian VK (2009) ‘Ordu on the Black Sea’, in Hovannisian RG (ed) (2009):297–342.

Kastrinakis AP (2008) ‘Summary of PhD proposal’, The national, cultural and religious identity of Pontian Greeks, based on the Italian, American diplomatic archives and the Vatican archives, during the period from 1850 to 1924,: www.peristereota.com/Abstracts/abstract_en13.html

Kostos SK (2010) Before the silence: archival news reports of the Christian holocaust that begs to be remembered, Gorgias Press, New Jersey.

Kurtides TP (1973) The province of Melanthia of Pontos, Publisher unknown, Thessaloniki.

Mango A (2002) Ataturk: The biography of the founder of modern Turkey, The Overlook Press, New York.

Payaslian S (2009) ‘The fate of the Armenians in Trebizond, 1915’, in Hovannisian RG (ed) (2009):271–296.

Saltsis ID (1955) Chronicle of Kotyora: historical monograph of the city of Kotyora (Ordu) from Pontos, (in Greek), Emm. Sfakianaki, Thessaloniki.

Topalidis S (2019) History and culture of Greeks from Pontos Black Sea, Afoi Kyriakidi Editions SA, Thessaloniki.