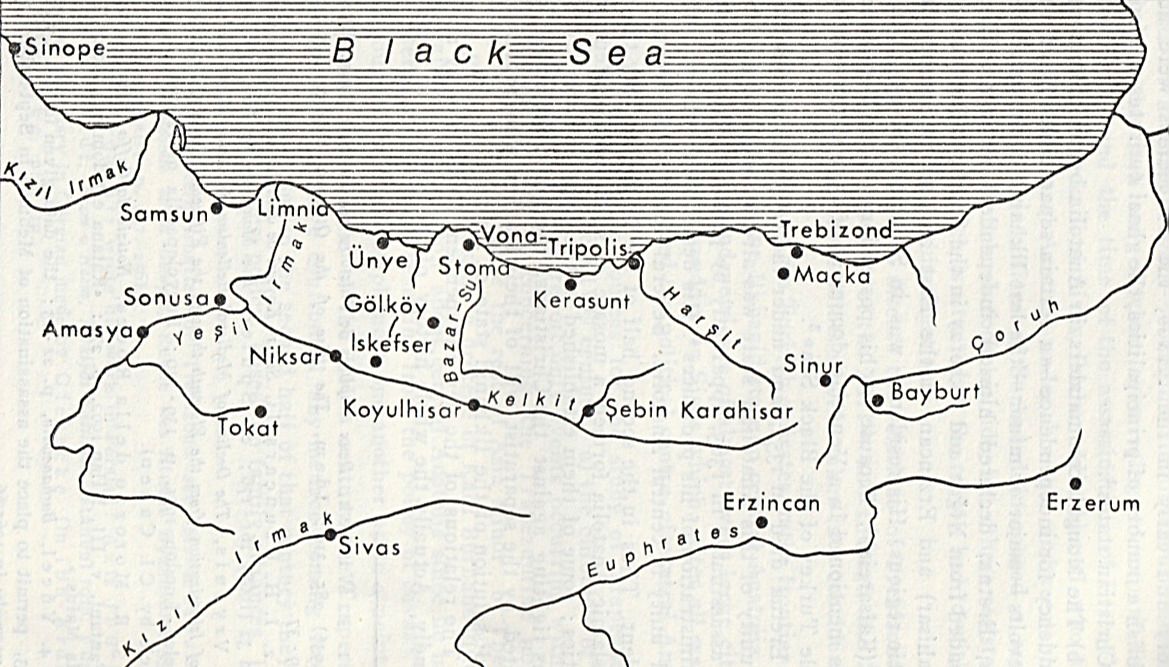

Fig. 1: North-east corner of Anatolia (scale: Amasya to Trebizond = 330 km, Zachariadou 1979:335)

Sam Topalidis (2025)

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist

Trebizond and Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II

In 1456, the Ottoman Turk prefect of Amasya attacked Trebizond (Fig. 1, modern Trabzon) and captured about 2,000 people. The Trebizond emperor, John IV Komnenos1, negotiated to keep Trebizond and return the captives by paying a tribute of 2,000 gold coins to Ottoman sultan Mehmed II (Plate 1).2 Later John IV sent his brother David (who became the last emperor of Trebizond) to the sultan to confirm a treaty, which was agreed, but now the annual tribute rose to 3,000 gold coins3.

The sultan wished to reunify the old Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire territories around Constantinople under Ottoman control and thus he was determined to take possession areas such as Sinope and Trebizond (Inalcik 1960). From 1458 however, David Komnenos established an anti-Ottoman alliance with Uzun Hasan, chieftain of the Akkoyunlu, a powerful Turkmen tribe that controlled much of eastern Anatolia and Turkman Ismail Isfendiyaroğlu (brother-in-law of the sultan) from Sinope. Uzun Hasan’s wife was a daughter of emperor John IV Komnenos (Freely 2009:68).

Plate 1: Portrait of sultan Mehmed II, 1480 (by Gentile Bellini, Source)

It was claimed that the army the sultan took in 1461 on his conquest comprised 140,000 cavalry and infantry (Bryer and Winfield 1985:60). The army reached Ankara in mid-May with a supply train consisting of 100 horse drawn wagons (Freely 2009:68).4 [Based on logistics to feed the army, the cavalry horses and the beasts which carried supplies in northern Anatolia, his army must have been considerably less than 140,000 combatants.]5 The sultan’s navy of about 150 ships sailed from Constantinople under Kasim (Kaldellis 2014:345).

The sultan’s army marched to Sinope (on the Black Sea coast), where it arrived after the sultan’s fleet under Kasim. Ismail Isfendiyaroğlu of Sinope surrendered. Kasim then sailed to Trebizond. The sultan and his grand vizier, Mahmud pasha, marched to Sivas, then proceeded to the north-east towards Bayburt (Fig. 1). In late July, the army divided. [This would make sense in order to capture any food and find enough fodder and water for the animals and for the easier movement of the army.] Mahmud pasha took the westerly route while the sultan took the easterly route north to Trebizond. The fleet besieged Trebizond from after mid-July (Bryer and Winfield 1985:61). On route to Trebizond the sultan had made an agreement with Uzun Hasan that the sultan would not attack Hasan’s lands if Hasan did not provide any assistance to the emperor of Trebizond (Kaldellis 2014:359).

The sultan’s fleet besieged Trebizond with its formidable walls and defences6 (Plate 2) for 32 days. Mahmud pasha reached Trebizond on or just before 14 August. He proposed terms of surrender to his Christian first cousin, George Amiroutzes7 telling him to give the following message to David Komnenos:

If you hand the city over immediately to the sultan, he will provide you with land, just as he bestowed prosperity upon Demetrios, the ruler of the Greeks of the Peloponnese … But if you do not obey and decide to resist, know that your city will soon be enslaved. For he will not depart before he has captured you all and delivered you over to a horrible death (Kaldellis 2014:359–360).

Plate 2: Part of the walls of Trabzon (author’s photograph 2018)

Amiroutzes convinced David Komnenos to surrender on 15 August 1461, the day the sultan arrived with his army. The emperor’s officials, other notables and some of the empire’s wealthiest families and their belongings, were sent by ship to Constantinople (Lowry 2009:6).

The sultan then selected around 1,500 young men and women from Trebizond and the surrounding countryside, the overwhelming majority of whom came from the latter. Of this number, around 800 of the boys were sent to Constantinople to join the Janissary Corps. The remaining around 700 young women and men were enrolled in the personal service of the sultan and also sent to Constantinople. The rest of the inhabitants remained in Trebizond and had the ownership of their properties confirmed. The sultan appointed a governor and left a garrison of 400 Janissaries in the citadel and stationed 132 guards (Azaps8) in the town (Kaldellis (2014:365), Lowry (2009:22)).

The sultan’s combined army then marched west along the coast but this road provided no fodder for his animals. Kasim supplied the army by sea but many beasts were still lost. Near Samsun, Mehmed turned inland reaching Adrianople (Edirne, in eastern Thrace) in early December. The fleet returned to Constantinople (Bryer and Winfield 1985:61). The sultan then ordered that the former emperor of Trebizond and his family be taken to Adrianople (Kaldellis 2014:363).

Murder of Former Emperor of Trebizond David Komnenos

In early 1463, David Komnenos’ niece, the wife of Uzun Hasan, sent letters summoning either a son of David or his young nephew to Hasan’s court. Amiroutzes handed these letters to the sultan, probably with a benign intent, so that it would not be said that Amiroutzes had concealed this matter. On reading these letters, the sultan became suspicious (Kaldellis 2014:365–367). David was accused of complicity in a plot against the sultan and imprisoned David with his wife and their children. The sultan then concluded to end the line of the last Byzantine claimants to the title of emperor by killing the male members of the family of Komnenos (Nicol 1996:123).

David, along with his sons and his nephew, were executed in November 1463. By showing the letters to the sultan, Amouritzes was proving his loyalty to the sultan (ehw.gr/asiaminor/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=3543). David’s wife, their youngest son (aged six years) and their daughter were spared (Freely 2009:69).

A Final Comment: Relationship Between Amiroutzes and Mehmed II

In Constantinople, Amiroutzes engaged in frequent theological and philosophical discussions with the sultan. In 1465, the sultan commissioned Amiroutzes to publish a translation of the Greek manuscript Geographica by Greek scientist Ptolemy (written in the 2nd century), into Arabic, as well as to compile all the Ptolemaic maps into a single very large map. Mehmed was delighted with the completed work (Freely 2009:96). Amiroutzes remained a Christian, but his two sons converted to Islam. Amiroutzes died sometime between 1470 and 1475.

Amiroutzes became very influential in Mehmed’s court. This enabled Mehmed to have a new view of the world and assist his expansion of the Ottoman empire (Modaffari 2020:20).

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

1. Just before the capture of Constantinople in 1204 by solders of the Fourth Crusade, the small 2. Christian Komnenoi Byzantine empire was established (1204–1461) with its capital at Trebizond. For details on the Komnenoi emperors of Trebizond see Topalidis (2024).

2. Mehmed II captured Constantinople in 1453.

3. Finlay (1851:478) calls these 3,000 gold pieces a paltry sum.

4. After the horses became bogged in mud their supplies were loaded onto 800 camels (which he had brought). The horses were then given to the sultan’s men (Soucek 2011:59). A camel can carry 136 kg in weight, so 800 camels could carry nearly 109 tonnes of supplies. A camel requires more than 4.5 kg of grain and extra fodder and about 38 litres of water each day (Engels 1978:14).

5. Words within square brackets ‘[ ]’ within a reference are the author’s words.

6. Trebizond’s walled town was protected on its eastern and western sides by ravines and on the north side by a cliff' overlooking a low foreshore (Bryer and Winfield 1985:10).

7. Born in Trebizond in 1400, Amiroutzes was a philosopher, theologian and writer. He served as the senior financial official and Prime Minister of the last Trebizond emperor, David Komnenos (1458–1461) (The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium 1991).

8. 132 Azaps were recorded in the c.1523 Ottoman tax records for Trebizond (Lowry 2009:32).

Sources

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Engels DW (1978) Alexander the Great and the logistics of the Macedonian army, University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Finlay G (1851) The history of Greece from its conquests by the Crusaders to its conquest by the Turks and of the empire of Trebizond 1204–1461, William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh.

Freely J (2009) The grand Turk: sultan Mehmet II – conqueror of Constantinople and master of an empire, The Overlook Press, New York.

Inalcik H (1960) ‘Mehmed the conqueror (1432–1481) and his time’, Speculum, 35(3):408–427.

Kaldellis A (2014) The histories: Laonikos Chalkokondyles, II (books 6–10), (translated into English by Kaldellis A), Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Lowry HW (2009) The Islamization & Turkification of the city of Trabzon (Trebizond) 1461–1583, The Isis Press, Istanbul.

Modaffari G (2020) ‘Portraying the world at the court of Mehmed II: the contribution of George Amiroutzes and Mehmed Bey to the translation of Ptolemy’s geography (1465), Bollettino Dell'associazione Italiana Di Cartografia 168:19–28.

Nicol DM (1998) The Byzantine lady: ten portraits, 1250–1500, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Soucek S (ed) (2011) Memoirs of a janissary: Konstantin Mihailović, (translated into English by Stolz B) Markus Wiener Publishers, Princeton, New Jersey.

Topalidis S (2024) Greek Pontos, Kyriakidi Bros Editions S.A., Thessaloniki.

Zachariadou EA (1979) ‘Trebizond and the Turks (1352–1402)’, Twelfth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies: The Byzantine Black Sea, Birmingham England, 18–20 March 1978, Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], 35:333–358.