Sam Topalidis, June 2022

Canberra, Australia

Read part 2

Read part 3

‘I will consider myself old when I can no longer dance.’ [ Sam Topalidis. ]

Dance is the movement of the body in a rhythmic way, usually to music and within a given space, for the purpose of expressing an idea or emotion, releasing energy, or simply taking delight in the movement itself.[ www.britannica.com/art/dance ] Dance must be one of the most basic actions performed by humans. Traditional Greek dance is an essential part of Greek culture. It is a statement of Greek nationalism and a source of great enjoyment. In the Greek diaspora, traditional Greek dance is most often taught by Greek cultural associations.

‘Traditional dance may be defined as dance transmitted from one generation to the next by continuous immersion rather than by formal teaching.’ In this sense, traditional dance is still practiced in the Greek countryside, although urbanisation/modernisation since World War II has caused a steady decline. Traditional dances have gradually become the province of dance groups, with a subsequent loss of feeling and increased emphasis on the spectacular.[ Raftis (1998:296).]

Dancing is a form on non-verbal communication between people and is beneficial both socially as physically. Dance is predominantly an aerobic exercise [although, during a vigorous dance it is approaching an anaerobic workout]. There are also significant changes to the chemical reactions of the brain that cause the release of ‘feel-good’ hormones during dance. Dance helps to decrease symptoms of dementia and improve balance and strength in Parkinson’s patients. The cognitive process of learning and repeating dance movements improve neural transmission in the brain.[ Wargo (2021:39). ]

The dance experience includes music, the rhythmic and repetitive movements of the body with the absence of competition, a personal pleasure and the reduction of stress that helps the dancers to escape problems and encourage introspective thinking. Older people who regularly participate in dance have better balance and are able to walk in a more brisk and steadier pace than their peers who do not dance (Plate 1.1).[ Argiriadou (2018:16–19). ]

Dance is where Greeks may achieve Kefi—an overwhelming soul and body experience that is expressed through laughing, dancing and singing.[ https://neoskosmos.com/en/2017/09/21/features/%ce%9aefi-a-greek-word-that-cant-be-translated/ ]

Many people are aware of the Zorba dance from the 1964 movie Zorba the Greek. However, the Zorba dance was created specifically for this film and the dance incorporates segments of other traditional Greek dances (like the Hasaposerviko). The music for the dance was composed by Greek composer, Mikis Theodorakis. I do not consider The Zorba dance a ‘traditional’ Greek dance and thus, it will not be discussed any further in this document.

Plate 1.1: 100 year old grandmother dancing Tsamiko in Nafpaktos (west Greece)

This work provides an introduction to the history of traditional Greek dance starting from ancient Greece, moving to the Roman and the Eastern Roman empire (often incorrectly called Byzantine empire) period and touching on the Venetian and Ottoman Turk occupation of Greece. Additional detail is provided on the role of traditional Greek dance in modern Greek culture followed by a brief discussion on Pontic Greek dance. A short final note ends the work.

Dance in Ancient Greece

Many believe that the origins of Greek dance date back to the 2nd millennium BC on Crete. Tradition has it that the Minoan civilisation (2500–1450 BC) on Crete had a great impact on the Mycenaean civilisation (1600–1200/1100 BC) who later occupied Crete.[ The Minoans on Crete spoke an unidentified Anatolian language. The Mycenaeans from the Greek mainland were the first to speak proto-Greek (Topalidis in press). ] At Palaikastro (eastern Crete) there are clay figurines of female dancers in a circle dating to 1350 BC (Plate 2.1), who also appear in the wall-paintings of the Late Minoan palace at Knossos, Crete.[ www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Dance/ ] Plate 2.2 shows a model from Crete of dancing men on a circular dance floor which dates to 1500–1450 BC.

The discoveries of artefacts in the Cyclades Islands (north of Crete), however, point to the development of music and probably, to the existence of dance, in much earlier times. In Crete, dance representations occur during 1900–1100 BC. The most important Minoan dance was the female circular dance performed in the context of the epiphany of the deity, during open-air religious rituals (Plate 2.3). The most characteristic gesture was the raising of the arms above the head, accompanied by a slight backwards inclination of the head.[ Mandalaki (no date). ]

Plate 2.1: Model of dancing women from Palaikastro, Crete 1350 BC, (author’s photograph 2017, Heraklion Museum, Crete).

Plate 2.2: Model of dancing men, Kamilari, Crete 1500–1450 BC, probably Minoan (author’s photograph 2017, Heraklion Museum, Crete).

Plate 2.3: Minoan gold ring 1500–1400 BC (2.1 cm diameter) Isopata tomb near Knossos, Crete Source

Much of the following discussion was sourced from Dr Alkis Raftis. We can appreciate the role of dance in ancient Greek society, but we do not have much information on how the dances were actually performed. After the fall of the Mycenaean Civilisation, references to dances occur in the Greek works [after around the 7th century BC] of Aristophanes, Aristotle, Plato, Plutarch, Xenophon and the tragic poets. This literary evidence was supplemented with representations of dancers on ancient Greek vases, reliefs and sculptures. We need to be wary of the interpretation of these representations of dance as it seems that neither the representations nor the texts and inscriptions refer to what we would define as traditional dance. They all deal with classical dances performed in the cities by well-trained amateur or professional dancers.

Today, the concept of dance is narrower than it was for the ancient Greeks. In ancient societies, one could dance with the hands or even the head and face without the movements being in any way rhythmic. Another basic observation is the unity of dance, music and song are but facets of a single phenomenon. In ancient Greece one could dance a poem, by expression through body movements aroused by the verses.

It was generally agreed that dance was essential for the moulding of a person’s personality, as well as preparation for battle. Dance, along with writing, music and bodily exercise, was basic to education. The young men in ancient Greece cities were taught dance. In Sparta they mainly performed martial dances and drilled to the rhythm of marches. Girls too were taught similar dance exercises which they performed in public. The Spartans even danced before battle.

In ancient Athens, the early poets trained the chorus, which included dance, in their theatre plays. In Plato’s exposition on education of the young—music, bodily exercise and dance held pride of place. He advocated that girls should also be taught dance. Plato (born c. 428 BC) distinguished three forms of dance:

1. The Pyrrhic or war dances.

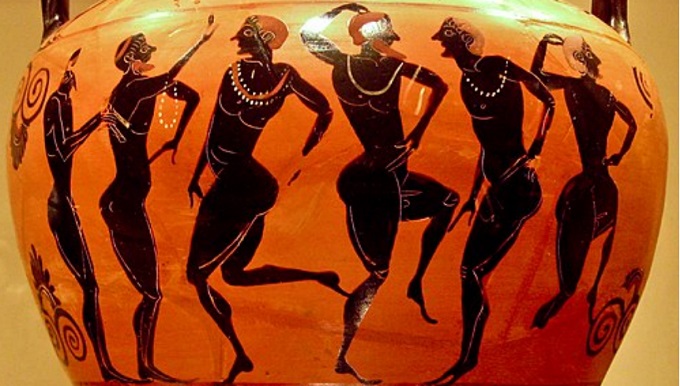

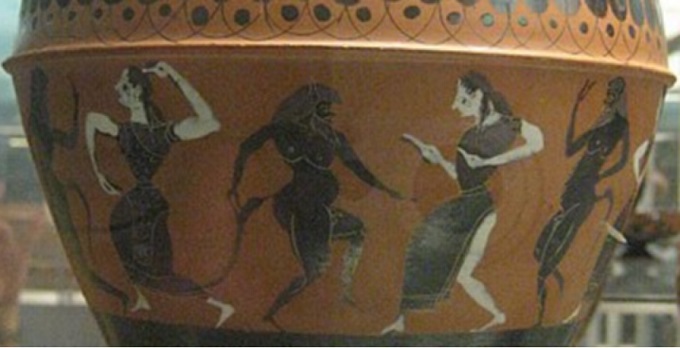

2. Social and religious dances, (Plates 2.4, 2.5) such as those performed at weddings, funeral processions and those performed in the ancient Greek tragedies and comedies.

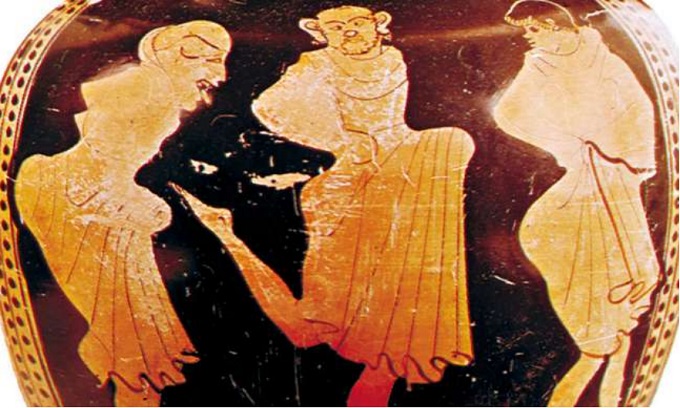

3. The Dionysian improper-satyric dances, whose dancers should have been punished severely [because they transgressed social morality].

The Pyrrhic dance, Plato claims, replicated the armed hoplite's movements in battle.[ A hoplite was a heavily armed ancient Greek foot soldier. ] The Pyrrhic dance seems to have been outstanding among the other known armed dances.

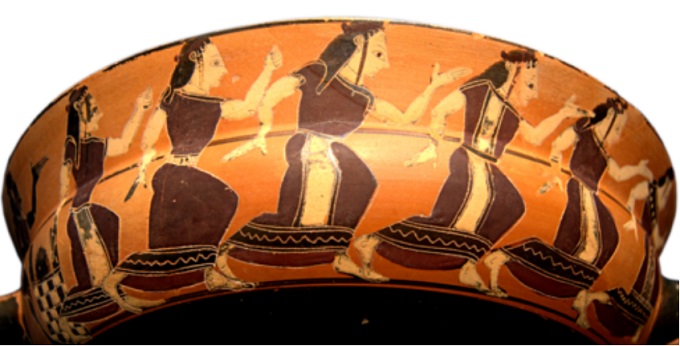

Plate 2.4: Attic Kylix, c. 560 BC, dancing Nereids (sea nymphs). Source

Plate 2.5: Dancers on Greek vase painting (no date) Source.

Another dance with formal movements was the Gymnopaedia which must have been like present-day gymnastics. It was performed annually in Sparta and imitated the movements of a wrestler, the dancers being unarmed and naked. The Pyrrhic and Gymnopaedia dances were performed by youths and maidens separately, to the sounds of a flute. Another dance, the Hyporchema, on the other hand, was danced by boys and girls together, while they were singing poems.

The Kordax (Plate 2.6), the mask dance associated with theatre plays of comedy, was regarded as unworthy of serious men. It was danced by one or more people, making ridiculous and vulgar gestures to the music of the double flute. The dance, Sikkinis, associated with satyric theatre drama plays must have resembled the Kordax but was performed much faster with effeminate gestures. The third type of drama, tragedy, also had its own particular dance, the Emmelia (a serious noble dance).

The names of other dances are known, but it is unknown how they were performed. For example, the Hymnenaios, danced by the bride with her mother and friends, was quick with many twists and turns. Dances were performed in honour of the dead and of different gods. Local and Dionysian dances were danced on feast days and at special ceremonies, such as the Panathenaea [an annual festival which was eventually celebrated every fourth year] in Athens and at Symposia (drinking parties or discussions after banquets which could involve dancing girls who sometimes kept the beat with a pair of clappers (Plate 2.7)).[ www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Dance/]

The dominant formation in ancient Greek dances seems to have been the circle—open, closed (Plates 2.1–2.2) or spiralling. As a rule, men and women danced separately.

Plate 2.6: Kordax dance, Greek vase painting, 5th century BC (www.britannica.com/art/Western-dance/Dance-in-Classical-Greece).

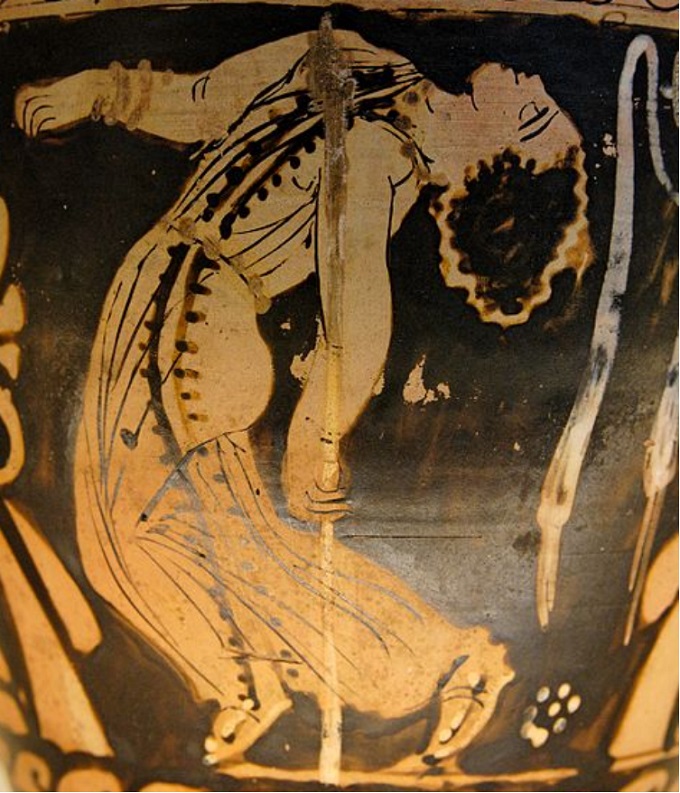

Plate 2.7: Kylix with dancing Maenad with clappers, c. 520–510 BC Source.

Ancient Greek dance could be individual or in groups. Individual dance was divided into solo performances (by professional entertainers) and freestyle dancing for leisure. In 400 BC, Xenophon and his Greek mercenaries who were travelling through the north coast of Anatolia described some of the Greek dances performed at a feast as follows:

… two Thracians stood up and performed a dance to the flute, wearing full armour. They leapt high into the air with great agility and brandished their swords. In the end one of them, as everybody thought, struck the other one, who fell to the ground, acting all the time. The Paphlagonians [from the north-west Anatolian coast] cried out at this and the other man stripped him of his arms and went out, singing the ballad of Sitalces. Then some more Thracians carried the man out, as though he was dead, though actually he had not been hurt in the slightest.[ Xenophon, Book VI, chapter 1. ]

Please note that Xenophon did not call this the Pyrrhic dance. Later, at the same feast, Xenophon very briefly mentioned the Pyrrhic dance as follows:

… [the Mysian] obtained the permission of one of the Arcadians who owned a dancing girl, and brought her in, after he had got her the best dress he could and given her a light shield. She then danced the Pyrrhic dance with great agility, and there was a lot of applause.[ Xenophon, Book VI, chapter 1. ]

The most (in)famous dancing characters [in Greek literature] were the male companions of Dionysos—the satyrs, half-men and half-goat. Often, the satyrs are dancing and chasing the maenads, female worshippers of Dionysos (Plates 2.8–2.9).[ www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Dance/ ]

Ancient Greek dance, together with its associated stories and figures, keep inspiring, writers, poets, painters, dancers, stage performers and many others throughout the ages and across many cultures around the world.[ www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Dance/]

Our attention will now focus on the development of dance in the Roman empire.

Plate 2.8: Dancing maenad on Greek cup c. 330–320 BC Source.

Plate 2.9: Athenian amphora with dancing satyrs and maenads 540–510 BC, Source.

Read Part 2 click here