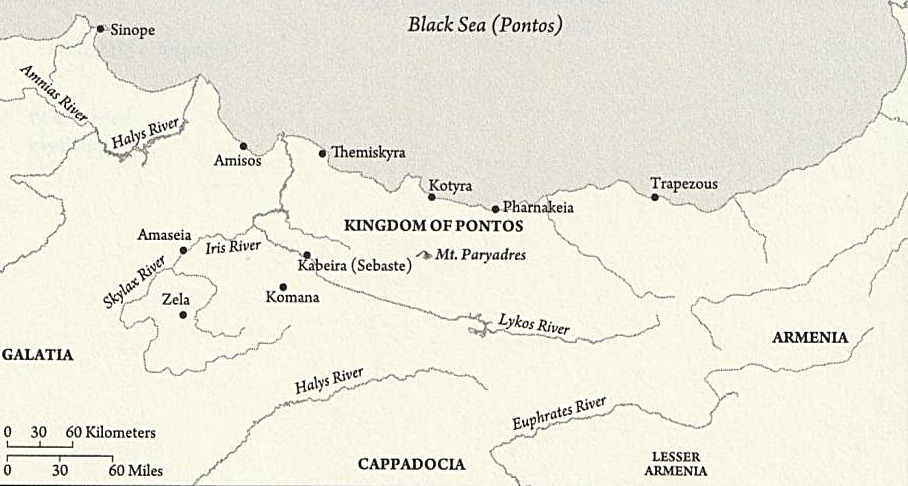

Fig. 1: Pontos, north-east Anatolia during the period of the Mithradatic dynasty (Roller 2020:xi)

By Sam Topalidis

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist (2024)

Introduction

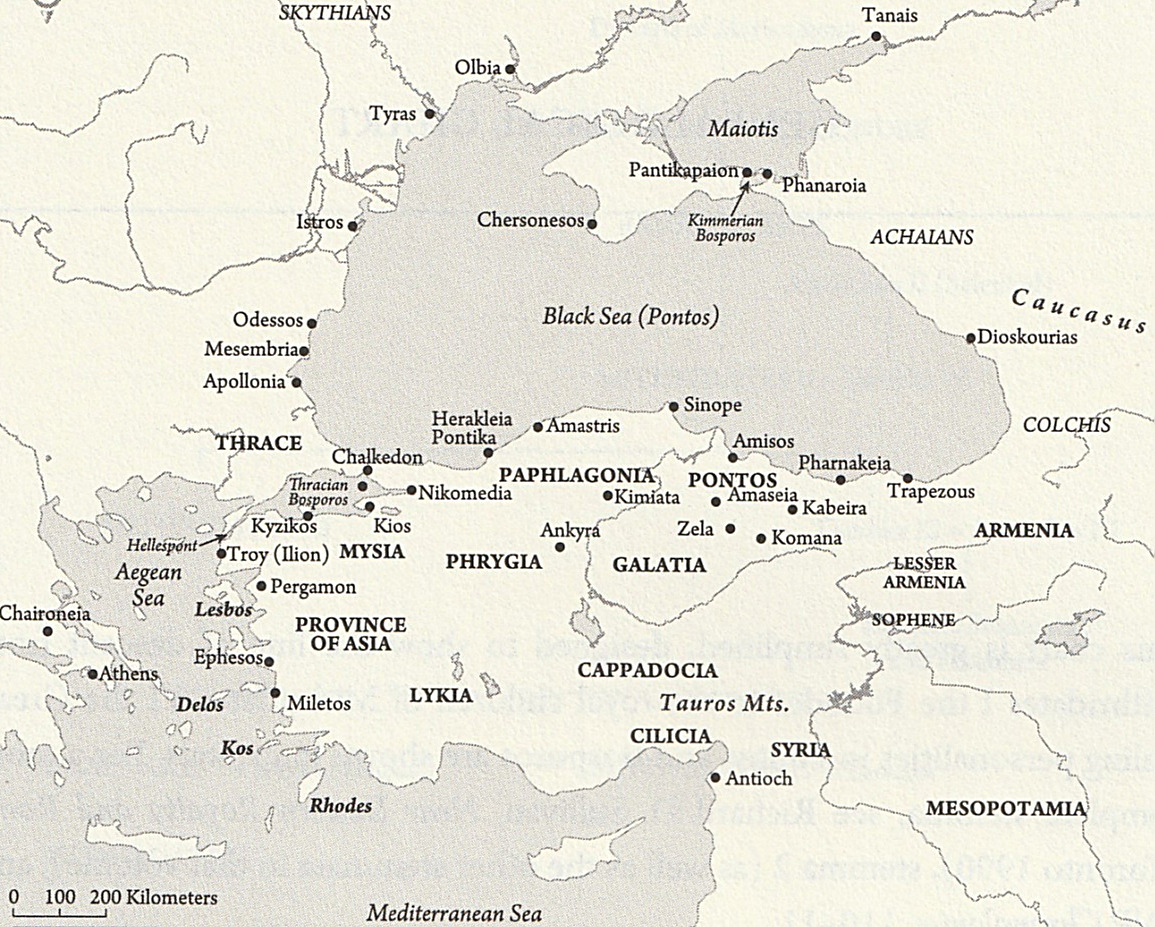

Mithradates I was a product of the world after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. Alexander left no plans for the organisation of his empire and thus there were 40 years of manoeuvring, as his territories had coalesced into three major kingdoms and several minor ones. Initially, one of these minor kingdoms was Pontos (c. 297–63 BC) in north-east Anatolia near the Black Sea (Fig. 1). Mithradates I, probably descended from Persian aristocracy and emerged as a follower of one of Alexander’s successors, Antigonos, the governor of Phrygia (Fig. 2).1 Eventually Mithradates became a threat and had to flee for his own survival to the mountains of northern Anatolia. He declared himself king (reign c. 297–266 BC) in an area that eventually became the kingdom of Pontos, with his capital at Amasya (Amaseia in Fig. 1) (Roller 2020:1–2).

Fig. 2: Anatolia and the Black Sea region (Roller 2020: xi)

Mithradates VI Ascends the Throne

After the creation of the kingdom of Pontos by Mithradates 1, there were six descendant kings before Mithradates VI, who was the last Mithradatic king. When his father Mithradates V was assassinated2, probably in 120 BC3, Mithradates VI, who was born in Sinope, was believed to be only 11 years old, so power passed to his mother, Laodike. Laodike reigned as regent surrounded by the men who had poisoned her husband. It seems that the young Mithradates possessed a strong will while his younger brother was more pliant. The advisors to the queen and the queen favoured the younger brother for succession because he would be easier to control. At this time, according to legend, Mithradates started taking homeopathic doses of poison, intending to develop resistance to as many poisons as possible. For his own safety he left Amasya and spent his early teenage years in remote parts of the country. Upon his return to the capital c. 116 BC, Mithradates had his mother and younger brother arrested as well as all those who were implicated in his father's death. Mithradates probably overthrew the nobility of Amasya by winning support from the people as a prince forced into exile by a corrupt court (www.worldhistory.org/Mithridates_VI/).

Mithradates VI, the last and most famous Mithradatic king (reign 116 BC–63 BC, Plate 1) had at least eight known wives or partners, 15 sons and eight daughters (Roller 2020).

Plate 1: Marble head of Mithradates VI, 1st century (Source)

By at least 106 BC, it appears that Mithradates VI had gained control of Colchis (western part of modern Georgia, Fig. 2). Strabo, in the 1st century AD wrote that Colchis’ wealth was derived from its gold, silver, iron and copper. It also had timber and linen which were important in ship-building (Roller 2020).

Chersonesos in Crimea and other Greek cities around the Cimmerian Bosporus in northern Black Sea were attacked by Scythians and asked for assistance from Mithradates VI. In 108 BC, Mithradates’ forces defeated the Scythians and as a result he became master of the north coast of the Black Sea. The northern Black Sea area with Colchis were able to supply Mithradates with much grain, money and men for his armies. His ambition was greater and he sought a large Anatolian in addition to his Pontic empire (Scullard 2003:72–73).

First and Second Mithradatic Wars

Around 107 BC, the dynast of Lesser Armenia (south-east of Pontos and rich in natural resources) yielded his kingdom to Mithradates. Nikomedes III of Bithynia (north-west Anatolia) and Mithradates agreed to partition Paphlagonia (west of Pontos, Fig. 2) which lay between their kingdoms. By the end of the 90s BC, Mithradates had supposedly mobilised a large force including 400 ships, 250,000 soldiers and 44,000 cavalry. These figures are exaggerated, but massive forces were collected. In 89 BC, Rome was ready to respond to Mithradates’ expansionism and the First Mithradatic War between the Romans and Mithradates broke out (Roller 2020).

The war turned into an attempt to expel Romans from Anatolia and perhaps from the Greek peninsula. In 88 BC, Mithradates took the Roman province of Asia and ordered the slaughter of all Roman men, women and children in the Roman cities his armies encountered, as a response to the predatory ways of the Roman tax collectors and businesses. This tragically resulted in maybe 80,000 deaths, something that made Mithradates a monster in the eyes of Romans. In the same year, Mithradates invaded parts of Greece. Roman General Sulla with five Roman legions confronted Mithradates in Greece and took Athens. A further two battles ensued in Greece where the Romans were again victorious (Roller 2020). This ended the war in Greece. In Anatolia, Mithradates’ supporters realised that they had backed a loser and Pontic control began to disintegrate. Mithradates’ brutal treatment of individuals and towns that deserted his cause merely hastened the end. After further defeat he accepted the lenient terms offered by Sulla (McGing 2009).

This First Mithradatic War ended in 85 BC. In 83 BC, the Roman General Licinius Murena, anxious to start a war that might yield him a triumph in Rome, marched Roman forces through Cappadocia (Fig. 1) where he was defeated by Mithradates’ forces. In 81 BC, Sulla, now dictator in Rome, ordered Murena to stand down which ended this Second Mithradatic War. The result was that Mithradates’ position had been strengthened (Roller 2020).

The Third Mithradatic War

In 75 or 74 BC, the king of Bithynia died and left his kingdom to Rome. This was unacceptable to Mithradates who installed his own king there. The Romans demanded that he remove his choice and when he refused, declared war which resulted in the Third Mithradatic War (73–63 BC). The Roman General Cotta was defeated, but Roman General Lucullus drove Mithradates out of Bithynia and then invaded Pontos. Mithradates was driven back to Armenia where he was welcomed at the court of his son-in-law, Tigranes. Lucullus requested that Tigranes surrender Mithradates. Lucullus was aware of the lingering anti-Roman sentiment in Anatolia and tried to win the people by lowering taxes and rebuilding towns. Around 69 BC, Tigranes refused to extradite Mithradates and so Lucullus marched on Armenia, but Tigranes and Mithradates had both escaped (www.worldhistory.org/Mithridates_VI/).

After defeats by Mithradates’ forces, as well as dissentions among his soldiers, Lucullus was replaced in 66 BC with Pompey. In the same year, Pompey defeated Mithradates and the king fled to the Cimmerian Bosporos (northern Black Sea) where his son, Pharnakes II, conspired to eliminate his father. The elderly Mithradates, realising his demise, committed suicide in 63 BC. Pompey, at his own expense, ordered a full royal burial for Mithradates in the royal tombs at Sinope. Pharnakes II then became king of Cimmerian Bosporos and when he started to attack Pontos, Julius Caesar pushed him north to Bosporos where Pharnakes was killed. From 39 to 37 BC, Mark Antony returned Pontos to the son of Pharnakes II, after which Polemon of Laodikeia was selected as king of Pontos. Pontos remained a kingdom allied with Rome until the 60s AD when it became part of the Roman empire (Roller 2020).

Mithradates VI Legacy

Over the first three decades of his reign, much of the Black Sea areas and eastern Anatolia were brought under Pontic control, culminating in 88 BC, when Mithradates took the Roman province of Asia in western Anatolia (Thonemann 2016:45).

Mithradates VI was regarded by his people, as well as those of neighbouring regions, as their saviour from the oppression of the Roman empire and by the Romans as their most formidable and hated enemy since Hannibal (247–183 BC) (www.worldhistory.org/Mithridates_VI/).

Under Mithradates VI the official language of his kingdom was Greek.4 While there were a few Greek settlements on the northern coast of Anatolia, their cultural influence did not spread far inland (Scullard 2003). Mithradates VI would generate interest among Greeks and Romans for hundreds of years after his death (Roller 2020:97).

Mithradates personal conception as the new Alexander was a piece of propaganda (Roller 2020). His propaganda also included minting an impressive amount of coins (Plate 2) (Farias 2021).

Plate 2: Tetradrachm of Mithradates VI (35.5 mm), Pergamon mint 74 BC (Source)

Conclusion

Mithradates VI was a belligerent adversary of the Roman empire. He ruled his kingdom of Pontos and beyond for over 50 years and his reputation lingered for hundreds of years after his death. He murdered around 80,000 innocent Roman men, women and children and tried to liberate Anatolia (at least) from the Roman empire.

Acknowledgements

I wish to warmly thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments.

References

1. Alexander appointed Antigonos governor of Phrygia and upon Alexander’s death (323 BC) he also became the governor of Pamphylia (between Lykia and Cilicia, Fig. 2) and Lykia (www.britannica.com/biography/Antigonus-I-Monophthalmus).

2. His kingdom probably became the largest political entity and wealthiest in Anatolia (Roller 2020:89).

3. Also in the 120s BC, Rome had a ‘toe-hold’ in Anatolia by establishing the Roman province of Asia in western Anatolia (Fig. 2) which was subjected to exploitation by Roman tax-farmers (Thonemann (2016).

4. Mithradates was educated in Greek learning and was interested in cultic matters and music (Roller 2020:196).

Sources

Farias FM (2021) Before the vespers: political propaganda and the struggle for legitimacy in the first decades of Mithridates VI Eupator’s reign, University of Brasilia honours thesis, Brasilia, Brazil.

McGing B (2009) ‘Mithridates VI’, Encyclopaedia Iranica at: www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mithridates-vi-eupator-dionysos

Roller DW (2020) Empire of the Black Sea: the rise and fall of the Mithridatic world, Oxford University Press, New York.

Scullard HH (2003) From the Gracchi to Nero: a history of Rome from 133 BC to AD 68, 5th edn, Routledge, London.

Thonemann (2016) The Hellenistic age, Oxford University Press, Oxford.