Plate 1: Atatürk Boulevard, Ophis (2024, Source: www.of.bel.tr)

Sam Topalidis (2024)

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist

Introduction

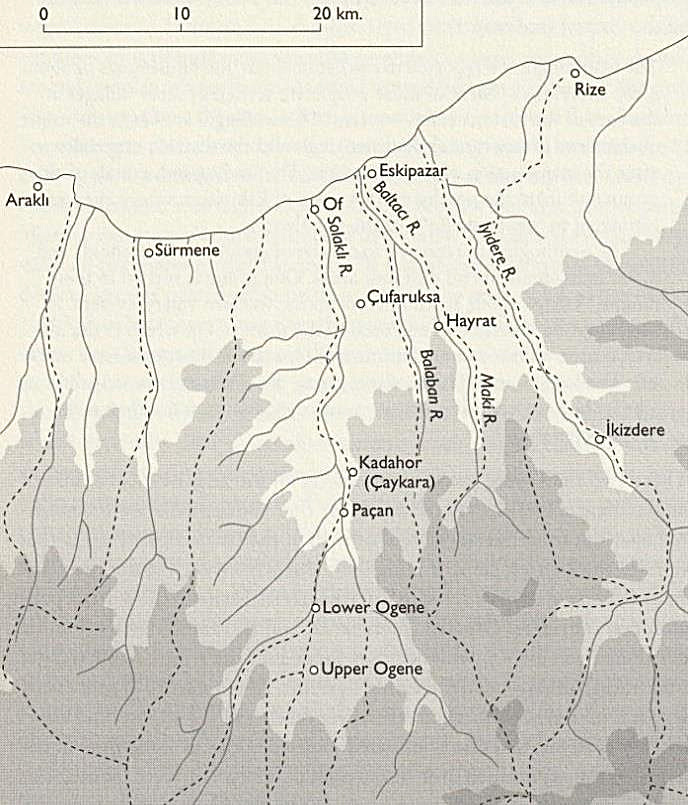

Ophis is a town at the mouth of the Solaklı river and a district in Pontos in the north-east corner of Anatolia (Türkiye) on the Black Sea coast (Figs 1–3, Plate 1). The town is called Of1 by Turks and is around 52 km east of Trabzon. In this article it will be referred to as Ophis. There is no definitive explanation on how the town originally received its name.

The population of Ophis is 21,630 and the Ophis district 43,590 (2022 estimates, Source: biruni.tuik.gov.tr).

Tea and hazelnut farming are important sources of income and recently tourism (especially from Arab tourists visiting Uzungöl (Fig. 3), south of Ophis) has also become important. Following tradition, many villagers spend summer on the plateau and the winter in the village (Özhan Öztürk, personal communication 2024).

From the town of Ophis, the valley rises dramatically southwards towards the Soğanli pass at 2,750 m beyond which the road continues on to Bayburt and the Anatolian plateau (Poutouridou 1997:47). Bryer and Winfield (1985) state that the end of the road that connects Ophis to Bayburt2 was constructed in 1916–1917 during the Russian occupation in World War I and was not previously a trade route of any importance. Prior to World War I, the inland route from nearby Sürmene was a preferred route.

The Oflus (from Ophis) are one of the peculiar peoples of eastern Pontos. The Oflus seem to have been Greek, as place-names along their valley demonstrated. After 1461, Ophis became Muslim by a much slower process when compared to Trabzon, but the valley retained its Romeyka Greek speech (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

The Oflus maintain a complicated love-hate relationship with their own history. Ophis is famous throughout Türkiye for the number of the religious scholars it produces, yet until a decade or so ago, the interpretation of the Quran was still being conducted in the local Romeyka Greek dialect (Poutouridou 1997:62).

Fig. 1: Lands from Arakli to Rize, east of Trabzon in north-east Anatolia (c.1923, Meeker (2002:18))

Greek Colonisation

It is assumed that ancient Greeks colonised Ophis sometime after 400 BC, after Greeks from Sinope had colonised Trabzon in the 6th century BC. Initially, the Greeks probably had to force the indigenous Anatolian natives from the Ophis area. Later these local natives must have comprised part of the population in Ophis. According to Bryer et al. (1972–1973) there is no evidence of Greek monuments in the town.

In 400 BC, when Xenophon and his almost 10,000 Greek mercenaries marched north into Trabzon, he reported many groups of Anatolian natives living around Trabzon. The name of the group of natives who lived around Ophis is unknown.

Mithradates Kingdom of Pontos

Although the army of Alexander the Great (reign 336–323 BC) defeated the Persians in Anatolia, the Greeks did not march north to conquer the Black Sea coast. These areas however, accepted Greek authority (Şerifoğlu and Bakan 2015). In 302 BC, Mithradates I, of Persian descent, established the kingdom of Pontos along part of the southern Black Sea coast (Roller 2020). Mithradates and kings from the same family ruled over the area from Heraclea (west of Sinope) east to Trabzon and beyond around the Black Sea coast (Fig. 2) until Mithradates VI3 was defeated by the Romans in 64 BC (Erciyas 2001).

Fig. 2: Pontos, north-east Türkiye (Bryer and Winfield 1985:iii)

Pontos remained a kingdom allied with Rome until the 60s AD when it then became part of the Roman empire (Roller 2020). Later, with the division of the Roman empire, it became part of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire.

Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire

As a result of the Fourth Crusade’s sacking of Byzantine Constantinople in 1204, the small independent Komnenoi Byzantine empire of Trebizond in north-east Anatolia was formed (1204–1461). This empire, which included areas to the east of Trabzon like Ophis, was Orthodox by religion and Greek by language. With the surrender of Trabzon to the Ottoman Turks in 1461, a process of Islamisation began in the Anatolian north-east.

Fig. 3: Ophis valleys north-east Türkiye (Of to Çaykara=24 km, part of Trabzon region map in Turkish, Trabzon Tourist Centre, date not stated)

Ottoman Occupation

After 1461, the Ophis area came under Ottoman Turk control. Although the Christian inhabitants of the Of valleys remained the majority until the latter half of the 17th century, many Oflus remained speaking Greek Romeyka (see below) rather than adopting Turkish (Poutouridou 1997:47). In fact, many Turkish settlers who moved to the Ophis valleys also became Romeyka speakers since it was the major local language (Mackridge 1987). In comparison, the town of Trabzon became over 50% Muslim as recorded in the 1583 Ottoman tax register.4

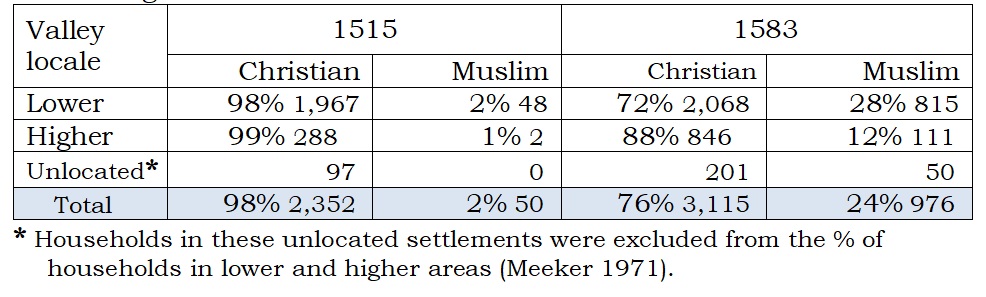

According to Umur (1951), the Ottoman tax registers from 1515 to 1583 record between 58 and 73 settlements respectively in the Ophis valleys. Between these dates the number of Christian households had decreased from 98% to 76% (Meeker 1971). Meeker concluded that the Christians had begun to retreat to the upper valleys away from the areas showing an increase in the number of Muslims (Table 1).

Table 1: Percentage and number of Christian and Muslim households, Ophis valleys (lower & higher), 1515 and 1583 Ottoman tax registers

Derebeys

From the late 17th century, military fiefs and derebeys (feudal valley lords) were effectively independent from the Ottoman government in Istanbul. By the end of the 18th century, few Anatolian provinces were under the direct control of the central government (www.britannica.com/topic/derebey). The Pontic derebey families brought anarchy to the Trabzon region. To non-Muslims, the local derebey wars brought misery. The derebeys’ authority was recognised by the provincial governor and the Ottoman government on feudal terms in the form of payment of a tithe (paid as a compulsory tax to government) and military service. These corresponded to the monetary and service tributes paid by its citizens, but the derebeys required recruits for their armies and, when Christians could not give military service, they demanded Christians become serfs (Bryer 1970:44).

Finally, the Ottoman sultan destroyed the derebeys which occurred in Trabzon between 1812 and 1840 (Bryer 1969). By the 1830s, the Ottoman provincial government had destroyed the older fortified hilltop residences of the derebeys of Ophis and Surmene (Meeker 2002).

From 1840

In 1879, it was estimated that out of 10,000–12,000 families from the Ophis area, 8,000–10,000 spoke Romeyka Greek, but only 192 were [openly]5 Christian (Bryer 1968:110). In 1893, Lynch observed:

There are whole villages on this seaboard whose inhabitants are Muslim … yet their Greek origin is established both by history and by the traditions which they themselves still in part retain. Thus take [Surmene] and Of [Ophis], two considerable villages on the east of Trabzon. These versatile Greeks are as famous now for their theological eminence as they were formerly under the Eastern empire, with this difference, that whereas in those days they supplied the Church with bishops, it is now mollahs that they furnish to Islam. Yet, fanatical as they are, they still hold to certain customs which connect them with the old faith they once served with such distinction and have, no doubt, since persecuted with equal zeal. Under the stress of illness the image of the Madonna again makes her appearance, suspended above the sick-bed; the sufferer sips the wine from the old cup of the Communion, which still remains a treasured object with the whole community, much as they might be puzzled to tell you why (Lynch 1901:11–12).

20th century

According to the 1903 Trabzon Provincial Yearbook, 68,853 men and women6 lived in the Ophis district (Agiralioglu and Agiralioglu 2023). The 1910–1912 Greek population count in northern Anatolia recorded only 1,855 Greeks in the county of Ophis. In comparison, the nearby Surmene county recorded 9,715 Greeks while the Trabzon county recorded 25,816 Greeks (Alexandris 1999:64).

From March 1916 to early 1918, during World War I, Ophis was occupied by Russian forces (Note 1). In May 1916, Russian army officer Sergei Mintslov reported on his visit to Ophis.

Its white mosque with a tall needle of a minaret could be seen from a long way off. There had been a battle near Ophis. A fleet was stationed opposite … large holes from shells could be easily seen in the walls of the houses. … The Turkish trenches stretched along on the heights covered with thick bushes to the west of the small town. In places, shells from our ships had swept them clean, as they say.

Ophis was full exclusively of militia. I did not see any civilians at all. Store depots had been built for the army there. Ophis is better than Rize. Its mosque is huge, its buildings also surpass in cleanliness and size the nastiness of Rize.

... The mosque was no doubt whitewashed, repaired and redecorated quite recently; its ceilings and walls gleamed with whiteness; large holes made by shells yawned around them. Some sort of office where three Russian soldiers worked as clerks was set up in one of the corners of the mosque.

Near Ophis, the floating [Russian] hospital ship Portugal was recently blown up by a German submarine. Our ships also sank some Turkish vessel and its mast stuck out of the water near our trawler (Mintslov 1923, 25 May 1916).

Chrysanthos, the Greek Orthodox metropolitan of Trabzon, conducted mass in the village church at Yiga [Ophis region, in either 1916 or 1917, under his ecclesiastic authority] where there had gathered 300 representatives of the region’s Muslims from the villages of Ophis. Among them were Muslim religious teachers and Muslim prayer leaders who were descendants of Greek Orthodox priests who had kept their crosses and bibles. These so-called ‘Muslims’ asked if they could be accepted back as Christians (their ancestors had converted to Islam). Chrysanthos advised them to wait until the end of war, so they wouldn’t be slaughtered for having renounced the Muslim faith in case the Ottoman government should reoccupy the areas (Chrysanthos (1970) in Poutouridou (1997:51)).

In the 1927 population count in Turkey [not a modern census] there were 64,885 men and women reported in the Ophis district. This was after the 1923 exchange of populations between Turkey and Greece. Apparently, only 1,200 Christians from Ophis emigrated to Greece during this exchange (Agiralioglu and Agiralioglu 2023:318, 328).

Where is Romeyka Spoken in Pontos Today?

After the battle of Manzikert in eastern Anatolia in 1071 when the Seljuk Turks defeated the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire and moved into Anatolia, the Greek spoken in Pontos became isolated from Greek spoken elsewhere. During his field research in the Ophis area, Professor Mackridge noted Romeyka Greek was spoken in at least 17 out of 21 villages in the district of Çaykara, seven out of 12 villages in the Dernekpazari district and six out of the nine in the Uzungöl district (Plate 2, Fig. 3) (Mackridge 1987).

Plate 2: Uzungöl (Source: www.kayak.com)

The most archaic form of Romeyka has survived among the Muslims from the Ophis region, who had predominantly Christian Greek ancestors. Although most male Romeyka speakers also speak Turkish, many women only speak Romeyka. The Ophitic Moslems’ Romeyka Greek has been influenced by Turkish, but their speech is not contaminated by modern Demotic Greek. There are hundreds of words in Romeyka that are unfamiliar in other Greek dialects (Mackridge 1987).

Today, Romeyka is spoken by maybe a couple of thousand people in a number of valley systems including Çaykara (south of Ophis), Tonya (south-west of Trabzon) and Sürmene (east of Trabzon) and Maçka.[ After a flood in 1929, homeless people from Beşköy (south of Surmene) were assigned houses west of Maçka (south of Trabzon). These houses originally belonged to Pontic Greeks who left during the exchange of populations (Özkan 2013:2). ] Communities refrain from identifying with the language out of fear that their heritage might be perceived as antagonistic to their Turkish-Muslim identity. Professor Sitaridou, argues that Romeyka constitutes a separate branch of Greek within the Greek language family—not a ‘daughter’ of medieval/modern Greek (Sitaridou and Sağlam 2020).

The highest concentration of Romeyka speakers comes from the region around Ophis. Although the number of speakers of Romeyka is decreasing, it remains a preferred language spoken when Romeyka speakers meet (Özkan 2013).

Conclusion

The ancient town of Ophis, east of Trabzon on the Anatolian Black Sea coast was probably colonised by Greeks sometime after 400 BC. The Greeks probably had initially to remove the local Anatolian natives. After the Mithradates kingdom of Pontos (302–63 BC) and subsequently Roman and Eastern Roman (Byzantine) hegemony, it came under the control of the Komnenoi Trebizond Byzantine emperors (1204–1461). The Ottoman Turks took control after the surrender of Trabzon in 1461. Compared to Trabzon, whose population were mostly Muslim by the late 16th century, in Ophis, an open Muslim majority was evident in the late 17th century. To this day there are some local Muslims who still speak the Romeyka Greek dialect which their mostly Greek Christian ancestors had spoken for many centuries.

Today Ophis is a conservative bastion of Islam with many Islamic religious schools.

Note 1

The Russian advance on the Trabzon area began in February 1916. The Ottoman army commander of Lazistan made a desperate stand in the district of Ophis. For the next two or three weeks, several thousand Ottoman troops, reinforced by thousands of irregulars and thousands of civilians, succeeded in [temporarily] halting the forward movement of a formidable Russian force (Meeker 2002:288).

Acknowledgements

I thank Özhan Öztürk for his discussion. I also warmly thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

1. The history of Ophis has some significant differences from the history of nearby Sürmene and Rize (Fig. 1). See the author’s articles A History of Sürmene and A History of Rize]

2. According to Mintslov (1923, 22 August), two construction teams and two engineering groups went to Bayburt and Ophis to build roads.

3. The kingdom of Mithradates VI encompassed Pontos and other areas around the Black Sea. See the author’s article: Mithradates VI King of Pontos

4. See the author’s article A History of Trabzon

5. Words within square brackets ‘[ ]’ within a reference are the author’s words.

6. Women were under-reported in Ottoman population counts.

7. After a flood in 1929, homeless people from Beşköy (south of Surmene) were assigned houses west of Maçka (south of Trabzon). These houses originally belonged to Pontic Greeks who left during the exchange of populations (Özkan 2013:2).

Sources

Agiralioglu S and Agiralioglu N (2023) ‘Population movements and their reasons in Trabzon city and Of district in the Ottoman period’, Eurasian Journal of Researches in Social and Economics, 10(1):305–332.

Alexandris A (1999) ‘The Greek census of Anatolia and Thrace (1910–1912): a contribution to Ottoman historical demography’ in Ottoman Greeks in the age of nationalism: politics, economy, and society in the nineteenth century, in Gondicas D and Issawi C (eds) (1999) Ottoman Greeks in the age of nationalism, 45–76, The Darwin Press, New Jersey, USA.

Bryer A (1968) ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes Part 2’, Archeion Pontou (Pontic Archives) 29:89–129.

Bryer A (1969) ‘The last Laz risings and the downfall of the Pontic Derebeys, 1812–1840’, Bedi Kartlisa, Revue de Kartvelologie, XXVI:191–210.

Bryer A (1970) ‘The Tourkokratia in the Pontos: some problems and preliminary conclusions’, Neo-Hellenika, 1:30–54.

Bryer AAMB, Isaac J and Winfield DC (1972–1973) ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes Part 4’, Archeion Pontou (Pontic Archives) 29:128–310.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Chrysanthos (1970) Biographical memoirs of the Archbishop of Athens, Chrysanthos of Trabzon [in Greek], Athens.

Erciyas DBA (2001) Studies in the archaeology of Hellenistic Pontus: the settlements, monuments, and coinage of Mithradates VI and his predecessors, PhD thesis, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, USA.

Lynch HFB (1901) Armenia: travels and studies, I, (reprinted 1967) Khayats, Beirut, Lebanon.

Mackridge P (1987) ‘Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey: prolegomena to a study of the Ophitic sub-dialect of Pontic’, Byzantine and modern Greek Studies, 11:115–137.

Meeker ME (1971) ‘The Black Sea Turks: some aspects of their ethnic and cultural background’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 2:318–345.

Meeker ME (2002) A nation of empire: the Ottoman legacy of Turkish modernity, University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Mintslov SR (1923) Trapezondskaia epopeia, (in Russian) [Russian accounts of Trabzon], (unpublished translation into English by R McCaskie), Sibirskoe Knigoizdatel’stvo, Berlin.

Özkan H (2013) ‘The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims in the villages of Beşkőy in the province of present-day Trabzon’, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 37(1):1–21.

Poutouridou M (1997) ‘The Of valley and the coming of Islam: the case of the Greek-speaking muslims’, Deltio Kentrou Mikrasiatikon Spoudon, [Centre for Asia Minor Studies Bulletin] 12:47–70.

Roller DW (2020) Empire of the Black Sea: the rise and fall of the Mithridatic world, Oxford University Press, New York.

Şerifoğlu TE and Bakan C (2015) ‘The Cide-Şenpazar region during the Hellenistic period (325/300–1 BC)’, in Düring BS and Glatz C (eds) (2015), Kinetic landscapes: the Cide archaeological project: surveying the Turkish western Black Sea region, 246–259, De Gruyter Open, Warsaw, Poland.

Sitaridou I and Sağlam E (2020) ‘Romeyka heritage in contemporary Turkey: socio-linguistic explorations of endangerment and preservation’, Heritage Turkey, British Institute at Ankara, 10:20–21.

Umur H (1951) Of Tarihi, Güven Basımevi, Istanbul.

Xenophon Anabasis (translated into English by CL Brownson 1922), Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, USA at: www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0202%3Abook%3D4