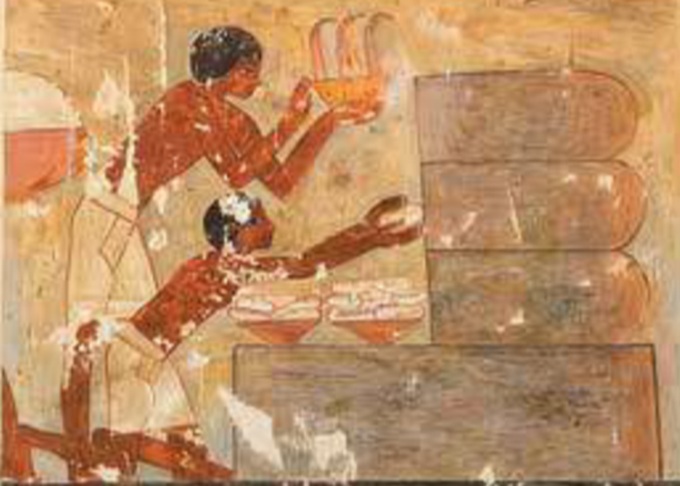

Plate 1: A smoker used when collecting honey 1600–1500 BC (Archaeological Museum Heraklion Crete, author’s photograph 2024)

Sam Topalidis 2025

(Pontic Historian and Ethnologist)

Prehistoric Beekeeping

Human harvesting of bee products from either wild or domestic bees has been practiced in Greece since around 5500 BC. Although no conclusive archaeological examples of prehistoric beehives exist, we know from pictorial evidence that beekeeping in hives did exist. So far, the earliest beeswax residue (from domestic bees) dates to the Minoan period 1600–1500 BC in north-east Crete. In prehistoric Crete, beeswax was used for lighting, which implies organised beekeeping. Just as modern apiarists do, ancient apiarists smoked the bees using smoking pots (Plate 1) in order to pacify them (Harissis 2017:18, 26).

Remnants of Greek prehistoric beekeeping paraphernalia are rare and only a handful of archaeological findings have been identified. Organised apiculture in prehistoric Greece was equally developed as it was in ancient Egypt (Harissis 2017:18).

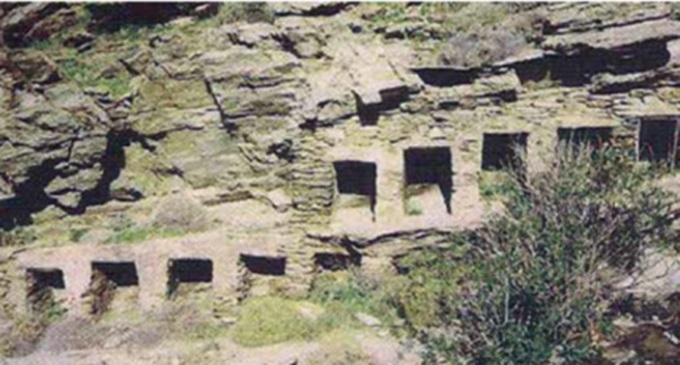

Two types of ancient ceramic beehives have been identified, horizontal (Plate 2) and upright. The horizontal beehive, a tabular container, was probably widespread in the Mediterranean area. The oldest known horizontal beehives dating to the 10th–9th century BC was discovered in modern day Israel.1 Horizontal beehives, dating to the classical period, were found in many places in Greece, such as Attica, Isthmia, Crete and the Aegean Islands. Their dimensions vary in length up to 60 cm with an opening measuring up to 39 cm in diameter (Harissis 2017:18–19). Horizontal pottery beehives that could only be open at one end are known from before 400 BC in Greece (Crane 1999).2

Plate 2: Wall painting depicting horizontal beehives c.1450 BC, tomb of Rekhmire, Egypt (Harissis 2017:19)

Each end of the hive was sealed, either with a wooden lid and mud, or with a ceramic disc or stone plate and mud. Small holes allowed the bees to fly in and out from the front end, while the back end permitted harvesting of the beehive. Horizontal beehives were laid on their sides and stabilised by walls, rocks or trees and could be stacked. During harvesting, the back lid was removed and the bees were driven by smoke from the back to the front of the hive. Hives with only one opening required a more difficult harvesting procedure. A traditional practice, also known in antiquity, was to elongate horizontal hives by adding a bottomless cylindrical terra-cotta stem (‘extension ring’), which was fastened between the lid and the end of the hive, which had projected rims. With this technique, the beekeeper could easily separate the extension ring from the main hive and harvest part of its crop without disturbing the inner parts; this entailed using less smoke, which was known to affect the taste of honey (Harissis 2017:19).

Besides these horizontal beehives, another type of beehive, the stone beehive, has been discovered on a gold signet ring from a tomb in Mycenae dating around 1400 BC. These stone beehives which were open at the front were widespread in the Aegean and Ionian Islands, as well as on mainland Greece (Plate 3) (Harissis 2017:21).

A second form of ancient ceramic beehive is a flowerpot-like container with a much shorter length than the horizontal variety. Its base is solid and flat and the rim broad and flaring. The open mouth was closed with mud or a ceramic lid or a flat rock. A hole near the base of the beehive allowed the bees to enter and exit. This is an upright beehive with a height of less than 50 cm. Archaeological findings in Attica, Korinthia and the Islands of Delos, Agathonisi and Chios confirm that upright beehives have existed since the archaic/classical period. It has been argued that the upright ceramic hive was in use since the Middle Minoan I period (2100–1850 BC) in Crete and the Islands of Kassos and Karpathos (Harissis 2017:21–22).

Plate 3: Traditional stone beehives, Andros Island, Greece (Harissis 2017:21)

Beekeeping in Ancient Greece

From 594 BC, beekeeping was on such a scale in Athens, that Solon of Athens passed a law, ‘he that would raise stocks of bees was not to place them within 300 feet [around 91 m]3 of those which another had already raised’ (Mavrofridis 2018:56).

Many ceramic beehives were discovered in the centre of Athens, the oldest was dating to the end of the 5th century BC. The most appropriate place to locate beehives in the city was on the roofs of houses. In ancient Athens, the discovered hives were open at one end (Plates 4–5). There is significant advantage in placing hives on the roofs of the ancient Athenian houses—the bees would fly higher above people. In addition, it would be more difficult for the honey to be stolen. In antiquity, honey was more than just a sweetener. It was also used in medicine, in textile dying, as a food preservative, in cosmetics, in the preparation of alcoholic drinks, as offerings to the dead and libations to the gods. (It was also used in hot

Plate 4: Beehive from a Greek county house 4th century BC (Archaeological collection in the Athens International Airport, author’s photo 2024)

Plate 5: Ceramic beehive, Thessaloniki, 3rd–2nd century BC (Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, author’s photo, 2024)

burials in the ancient cemetery of Athens—children were buried in two beehives. Beeswax was employed for writing tablets, making candles, lost wax painting (fromthehive.com.au/page/encaustic).) Ceramic beehives were found in six wax casting,4 sealing documents and letters, modelling figurines, making adhesives and pigments, in medicine, shipbuilding and hair care. Along with honey, wax was used for embalming in the ancient world (Mayor 1995:38; Mavrofridis 2018:53–58).

In the Hippocratic corpus (mostly 5th–4th centuries BC), honey was prescribed as medicine, commonly as hydromel (honey and water) or oxymel (honey acidified with vinegar). It is known today that honey does not contain the wide spectrum of healing properties ascribed to it in antiquity (Cilliers and Retief 2008).

Honey in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Era (4th century–1453)

In the Byzantine era, the production of honey and wax was important for monastic communities for nutritional and other practical needs. Evidence indicates the presence of beekeeping centres in the areas of western and central Anatolia, Mt Athos and in particular Chalkidiki, Thebes, Cyprus and Monemvasia (southern mainland Greece). Thyme honey, collected at the base of Mt Hymettus (south of Athens) and the honey production of Athens, especially that coming from the Kaisariani monastery, were widely valued (Germanidou 2017:94).

A type of perforated ‘face mask’ was depicted in a Byzantine miniature, included in a manuscript in the 11th century. Tools, mainly knives, used in the processes of extracting, transport and storing of beekeeping products were limited and very basic. For many centuries honey remained a delicacy, the only sweetener before the introduction of sugar following the Crusades. On the other hand, wax, which was used in making candles, was mixed with mastic from the Island of Chios to produce a dye which was applied on sculptures. Wax and honey were widely applied in medical and pharmaceutical treatments (Germanidou 2017:95–96).

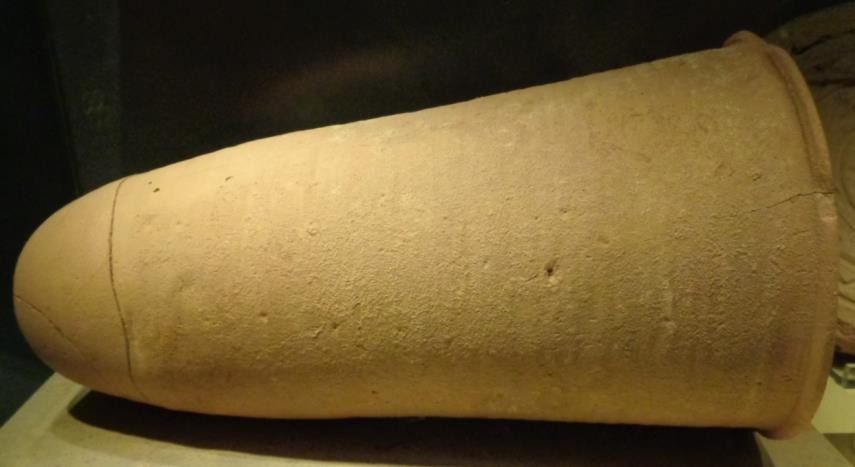

There were various forms of beehives depicted in Byzantine pictorial sources:

a. Woven wicker (e.g. in a mosaic pavement in Jordan)

b. Horizontal wooden plank

c. Ceramic, cylindrical shaped, open only in the front (Plate 6)

d. Horizontal tree trunks, or ceramic, open at both ends

e. Vertical tree trunks (Germanidou 2017:96).

Honey production has continued for millennia, but one product, ‘mad honey’, has achieved some significance and notoriety. It remains important for our understanding of honey which is normally benign but in one context has a potentially adverse impact on human or animal welfare.

Plate 6: Ceramic beehive from Delphi Greece, 6th century (Germanidou 2017:100)

What is ‘Mad Honey’?5

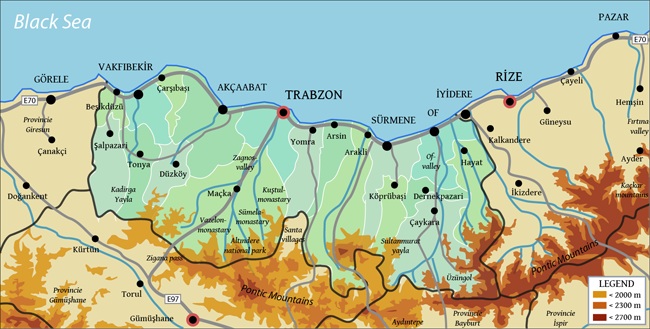

In the Black Sea region of north-eastern Türkiye (Pontos, which includes the greater Trabzon region, Fig. 1), ‘mad honey’ is produced from the nectar of the purple flowering Rhododendron ponticum (Plate 7) or the yellow flowering Rhododendron luteum (Plate 8), which contain grayanotoxin (a group of toxins))6 (Demir Akca and Kahveci 2012). Mad honey is generally reddish-brown in colour, with a sharp scent. In Türkiye, honey produced from these plants has a sharp and biting taste which irritates the throat (Gunduz et al. 2011; Gami and Dhakal 2017). Pontic Greeks knew mad honey as zanton or palalon (Harissis and Mavrofridis 2013).

Fig. 1: Trabzon region, north-east Türkiye (Trabzon to Rize = 67 km, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20298048)

Plate 7: Rhododendron ponticum (wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhododendron_ponticum#)

Plate 8: Rhododendron luteum (Wikimedia)

Today, mad honey is used as an alternative medicine for hypertension, diabetes, flu, gastrointestinal disorders, abdominal/gastric pain, arthritis, stimulating sex, viral infections, skin ailments, pain and cold. There are 18 known grayanotoxin forms; however, not all of them lead to poisoning (Ullah et al. 2018).

Rhododendrons and their toxins

The level of grayanotoxin in these plants varies depending on whether it is raining or not when the plants are blooming in late spring. When rainfall is low, the grayanotoxin ratio is high and this increases the likelihood of honey poisoning (Tekinsoy et al. 2017).

In general, small scale beekeepers along the Turkish Black Sea region sell their unprocessed honey in local and regional markets. This honey, which may contain grayanotoxin, is unregulated and there is no standard amount of grayanotoxin in 1 gm of honey (Demir et al. 2011). The threshold concentration for grayanotoxin toxicity in humans may vary from person to person (Sahin et al. 2015).

Mad honey can even overpower beasts. A young bear made headlines in 2022 when he was found unconscious near hives in Düzce (east of Istanbul) in the Black Sea region. It had keeled over after overindulging on mad honey (17 May 2024 issue of Hürriyet Daily News [Turkish Newspaper] www.hurriyetdailynews.com/mad-honey-turkiyes-elixir-with-dark-side-193630).

Historical references to ‘mad honey’ in Pontos

Mad honey poisoning was probably first recorded to have occurred in May 400 BC by some of Xenophon’s Greek mercenaries (Paradeisopoulos 2013), south of modern Maçka (south of Trabzon) (Fig. 1). Xenophon wrote:

… the soldiers who ate of the honey all went off their heads and suffered from vomiting and diarrhoea and not one of them could stand up, but those who had eaten a little were like people exceedingly drunk, while those who had eaten a great deal seemed like crazy, or even, in some cases, dying men. So they lay there in great numbers … the next day, however, no one had died and at approximately the same hour as they had eaten the honey they began to come to their senses; and on the third or fourth day they got up, as if from a drugging (Xenophon, Book IV, Chapter 8).

Another record of mad honey poisoning was by the Pontic Greek geographer Strabo (64–63 BC–c.25 AD) who identified the following episode in 67 BC which befell some of the soldiers under the Roman General Pompey who were fighting king Mithradates VI7 in Pontos:

The Heptacometae cut down three maniples [around 1,500 soldiers] of Pompey's army when they were passing through the mountainous country; for they mixed bowls of the crazing honey which is yielded by the tree-twigs and placed them in the roads and then, when the soldiers drank the mixture and lost their senses, they attacked them and easily disposed of them (Strabo, Book XII Chapter 3, 18). (Note 1.)

Another record of mad honey poisoning in Pontos was by Pliny the Elder (23–79 AD). In his Naturalis Historia he warned against consuming mad honey.

At Heraclia in Pontus, the honey is extremely pernicious in certain years ... There is a certain plant which, from the circumstances that it proves fatal to beasts of burden and to goats in particular, has obtained the name of ‘aegolcthron’ [Rhododendron Ponticum] … Persons, when they have eaten of it, throw themselves on the ground to cool the body, which is bathed with a profuse perspiration (Pliny the Elder, Book XXI, Chapter 44).

Modern diagnosis and treatment of patients with mad honey intoxication

The most common clinical findings in people affected after consuming mad honey is nausea, vomiting, dizziness, confusion and a feeling of fainting. Affected people do not usually present to hospital when this occurs and treatment based on local custom is rest and the consumption of salty water or salted yogurt. These people usually recover within a few hours. Patients usually present to hospital with abnormal heart rhythm or with very low heart rates (Tatli 2017). Other symptoms include abnormally low blood pressure. The severity of clinical symptoms of mad honey poisoning depends on an individual’s sensitivity to the toxin. The amount of honey needed for intoxication can be as low as one teaspoon and symptoms appear within 0.5 to 4 hours. The amount of mad honey intoxication also depends on the concentration of grayanotoxins in the honey (Gami and Dhakal 2017).

Most hospital patients with mad honey poisoning recover vital signs within the first 24 hours (Tekinsoy et al. 2017). Silici and Atayoglu (2015) reviewed 84 articles with nearly 1,200 cases of mad honey poisoning from 1981 with over 80% prepared by Turkish researchers. They determined it was more frequently reported in hospital in males (75%) and between the ages of 41 and 65 years and generally from the Trabzon region. There were no cases of death reported.

Nevertheless, there have been some fatalities from the 1800s when the medication atropine and normal saline were not available (Gami and Dhakal 2017). Fatalities have also been reported in south-west China (Zhang et al. 2017). (Note 2.)

Conclusion

Beekeeping has been practiced in Greece since pre-historic times. Beehives have taken various forms and its honey was used as more than just a sweetener. It was also used in medicine, in textile dying, as a food preservative, in cosmetics, in the preparation of alcoholic drinks, as offerings to the dead and libations to the gods and in encaustic painting. Beeswax was also employed for writing tablets, making candles, lost wax casting, sealing documents and letters, modelling figurines, making adhesives and pigments, in medicine, shipbuilding and hair care. Along with honey, wax was used for embalming in the ancient world.

Mad honey poisoning in humans was first recorded by the Greek General and historian Xenophon to have occurred in 400 BC, south of Trabzon in north-east Anatolia.

The consumption of mad honey, which contains grayanotoxin, continues today and can represent a public health problem along the Black Sea coast of Türkiye. Rhododendron species, the source of mad honey, are distributed around the world. Despite this, most hospital reports, predominantly from middle-aged males, of mad honey poisoning originate from Turkey. Mad honey intoxication and the honey’s antioxidant qualities need more medical research.

Notes

Note 1

The Heptacometae ambush required careful planning. Had the ambushers prepared the honey in too dense a concentration, the Romans would have likely developed symptoms quickly, thus minimising the number of soldiers who ingested the honey. Preparing a diluted dose of honey would have ensured that more Roman soldiers ingested the concoction. The failure of the Romans to detect the ruse seems very foolish (Turner 2023:4). The temptation must have been too great for them to stop and think before sampling the honey.

Note 2

Fatal honey poisoning occurs in south-west China. In the study by Zhang et al. (2017) there were 31 patients diagnosed with honey poisoning, eight died. It was believed that the poisoned honey was derived from the T. hypoglaucum plant (which has poisonous nectar) from the genus Tripterygium wilfordii.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their editorial comments on an earlier draft.

References

1. These beehives were made of unfired clay mixed with straw (Francis 2012).

2. Kalogirou and Papachristoforou (2017) provided information to indicate that such ceramic beehives offered good conditions for the development of bee colonies.

3. Words within square brackets ‘[ ]’ are the author’s own words.

4. Lost wax casting builds a mould around a sacrificial wax model. After the mould is set, the wax is melted out and forms a cavity where the metal or glass flows in.

5. This section is a cut-down and updated version of the author’s article on mad honey at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/633-mad-honey-of-pontos

6. Grayanotoxins do not pose a problem in commercially produced honey because the mass production of honey dilutes any possible toxic quantities (Gami and Dhakal 2017).

7. See the author’s article on Mithradates VI at: pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/896-mithradates-vi-king-of-pontos

Sources

Cilliers L and Retief FP (2008) ‘Bees, honey and health in antiquity’, Akroterion, 53:7–19.

Crane E (1999) ‘Traditional hive beekeeping in ancient Greece’, The world history of beekeeping and honey hunting, Routledge, New York.

Demir Akca AS and Kahveci FO (2012) ‘An indispensable toxin known for 2500 years: victims of mad honey’, Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 42(2):1499–1504.

Demir H, Denizbasi A and Onur O (2011) ‘Mad honey intoxication: a case series of 21 patients’, International Scholarly Research Network (ISRN) Toxicology, 2011, 3 pp.

Francis JE (2012) ‘Experiments with an old ceramic beehive’, Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 31(2):143–159.

Gami R and Dhakal P (2017), ‘Mad honey poisoning: a review’, Journal of Clinical Toxicology, 7(1), 5 pp.

Germanidou S (2017) ‘Honey culture in Byzantium - an outline of textural, iconographic and archaeological evidence’, in Hatjina et al. (eds) (2017):93–104.

Gunduz A, Turedi S and Oksuz H (2011) ‘The honey, the poison, the weapon’, Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, 22:182–184.

Harissis HV (2017) ‘Beekeeping in prehistoric Greece’, in Hatjina et al. (eds) (2017):18–39.

Harissis HV and Mavrofridis G (2013) “Mad honey’ in medicine from antiquity to the present day’, Archives of Hellenic Medicine, 30(6):730–733.

Hatjina F, Mavrofridis G and Jones R (eds) (2017) Beekeeping in the Mediterranean: from antiquity to the present, International Symposium of Beekeeping in the Mediterranean, Syros Island, Greece, 9–11 October 2014, Nea Moudania.

Kalogirou K and Papachristoforou A (2017) ‘The construction of two copies of ancient Greek clay beehives and the control of their colonies’ homeostasis’, in Hatjina et al. (eds) (2017):69–78.

Mavrofridis G (2018) ‘Urban beekeeping in antiquity’, Ethnoentomology, 2:52–61.

Mayor A (1995) ‘Mad honey!’, Archaeology, 48(6):32–40.

Paradeisopoulos IK (2013) ‘A chronology model for Xenophon’s Anabasis’, Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, 53:645–686.

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia at: www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D21%3Achapter%3D44

Sahin H, Turumtay EA, Yildiz O and Kolayli S (2015), ‘Grayanotoxin-III detection and antioxidant activity of mad honey’, International Journal of Food Properties, 1(12):2665–2674.

Silici S and Atayoglu AT (2015), ‘Mad honey intoxication: a systematic review on the 1199 cases’, Food and Chemical Toxicology, 86:282–290.

Strabo, The Geography of Strabo, (in Greek with an English trans by Jones H) 1969, V, The Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann Ltd, London. Tatli O (2017) ‘The Black Sea’s poison; mad honey’, Journal Analytical Research in Clinical Medicine, 5(1):1–3.

Tekinsoy A, Yasli SO, Saritas A, Gunes H, Kaya E and Sonmez FT (2017), ‘Analysis of mad honey (grayanotoksin) cases admitted to Duzce University School of Medicine Emergency Department’, Open Journal of Emergency Medicine, 5:13–24.

Turner MD (2023) ‘Mad honey and the poisoner king: a case of mass grayanotoxin poisoning in the Roman military’, Cureus, 15(4):1–5.

Ullah S, Khan SU, Saleh TA and Fahad S (2018) ‘Mad honey: uses, intoxicating/poisoning effects, diagnosis, and treatment’, RSC Advances, 8:18635–18646.

Xenophon, Anabasis, (Brownson C trans 1922), Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, USA.

Zhang Q, Chen X, Chen S, Ye Y, Luo J, Li J, Yu S, Liu H and Liu Z (2017), ‘Fatal honey poisoning in southwest China: a case series of 31 cases’, The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 48(1):189–196.