Plate 2: Tombs of the Mithradatic Pontic kings, Amasya. Wikimedia

Sam Topalidis (2025)

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist

Introduction

The population of Amasya is around 93,500 people (2025 estimate, worldpopulationreview.com/cities/turkey/amasya) and is located 125 km south of Samsun at about 400 m above sea-level (Plate 1, Fig. 1). It is a very attractive town in north-eastern Türkiye (in Pontos, Fig. 2) and lies in the gorge of the Yeşilirmak River, hemmed in by limestone cliffs which have pushed new development to the eastern outskirts of the town. The left bank of the river forms a narrow ledge on which a row of pretty houses stand near the river. Over them hang the monumental rock-hewn tombs of some of the Mithradates kings of Pontos (Plate 2) (Nişanyan and Nişanyan 2001:72).

Plate 1: Panorama of Amasya (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amasya)

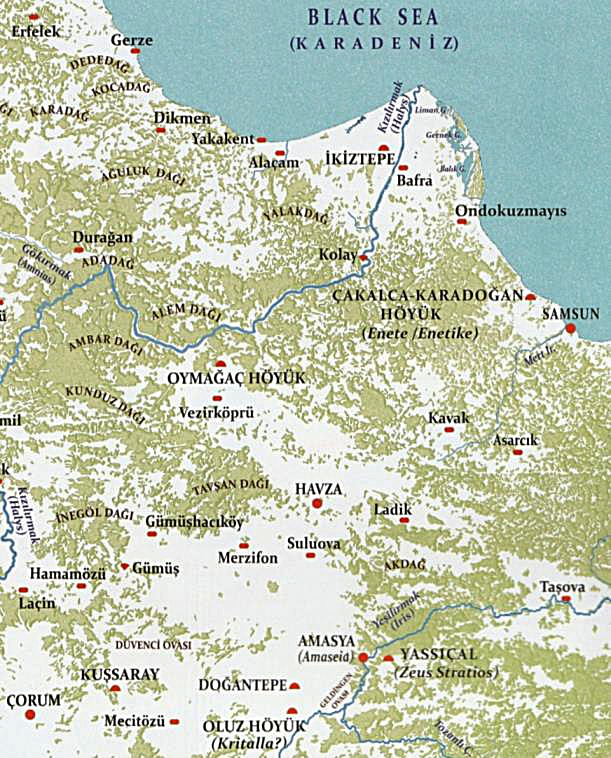

Fig. 1: Turkish map of Amasya area (Samsun to Amasya = 82 km, Dönmez Ş 2019:245)

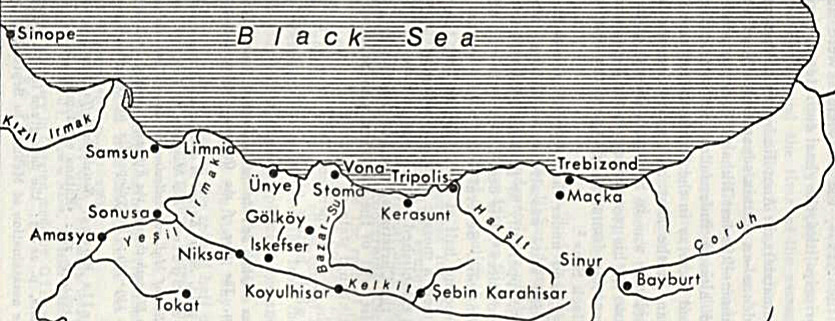

Fig. 2: North-east corner of Anatolia, Pontos (Amasya to Trebizond = 330 km, Zachariadou (1979:335))

Early History

Reliable information on the early human occupation of Amasya is sparse. The first recorded settlement at Oluz Höyük, 25 km south-west of Amasya, most likely was 4500–3500 BC. A 6th century BC, Late Iron Age settlement has also been found there (Dönmez Ş 2015; 2018).

Excavation of the Harşena Castle on Mt Harşena in Amasya (Plate 3) and from the area leading down to the Yeşilirmak River showed the settlement extended towards the river in the Iron Age, it also showed that the terraces contain cultural deposits from earlier settlements (Dönmez Ş 2014:11, 14).

Plate 3: Harşena Castle on Mt Harşena (Source)

In the 5th century BC, Amasya was under Persian control. When Alexander the Great (336–323 BC) defeated the Persian king Darius III in Anatolia, he did not advance north of Ankara (340 km south-west of Amasya). After the death of Alexander in 323 BC and the creation of the Hellenistic kingdoms, Mithradates I (of Persian descent) established the kingdom of Pontos no later than 302 BC (Koromila 2002).

Somewhere between 297 and 266 BC, Mithradates I established Amasya as the capital of his kingdom. In 183 BC, the capital was moved to Sinope by Pharnakes I (son of Mithradates III). He probably also took possession of the Greek settlements of Ordu, Giresun and possibly Trabzon on the Black Sea coast (Roller 2020:16, 58).

There are five rock-tombs in Amasya which belong to the Pontic kings (in chronological order) Mithradates I, Ariobarzanes, Mithradates II, III and Pharnakes I (https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6039/).

Greek geographer, Strabo (XXII: 3, 39) (born 63 BC) describes his home town of Amasya:

… it is an admirably devised city, since it can at the same time afford the advantage of both a city and a fortress; for it is high on a precipitous rock, which descends abruptly to the river and has on one side the wall on the edge of the river where the city is settled and on the other the wall that runs up on either side to the peaks. These peaks are two in number, are united with one another by nature and are magnificently towered. Within this circuit are both the palaces and monuments of the kings.

Around 67 BC, during the siege of Amasya by the Roman empire, the walls of the settlement were demolished (during the wars against Mithradates VI, king of Pontos (reign 116–63 BC)). Under the four century Roman occupation of Amasya, high town walls were constructed. In the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) period (from 4th century) in Amasya, many monasteries and churches were constructed. Several times between the 7th and 10th centuries the town was besieged by Arab invasions. In 1075, after 700 years of Byzantine rule, the Danishmends (a Turkmen dynasty, who were rivals of the Seljuk Turks) conquered Amasya (Etyemez 2011:63–64).

The Byzantine church believed to have been constructed in the 7th century was in 1166 converted into Amasya’s first mosque (Fethiye Mosque, Plate 4) (https://amasya.ktb.gov.tr/EN-262618/fethiye-mosque.html). In 1178, Amasya was annexed by the Seljuk Turks (Dönmez EEN 2014). With the defeat of the Seljuk Turks in 1243, the region came under the rule of the Mongol Ilkhanids (Etyemez 2011).

Plate 4: Fethiye mosque, Amasya (Source)

Ottoman Rule

In 1387, the Ottoman Turks annexed Amasya. In 1398, the youngest of Ottoman sultan Bayezid’s sons became the nominal governor of the town. The Ottomans made Amasya the administrative centre of the Rum province (which included Sivas, Tokat, Çorum and Amasya). All four of the 15th-century Ottoman sultans were trained in Amasya (Karatas 2011:2, 22).

In 1402, Timur (also known as Tamerlane, of Turkic and Mongol decent) defeated the Ottomans at the Battle of Ankara (McEvedy 1992). In 1434, Ottoman sultan Murad II sent his eldest son to Amasya as its nominal governor. In the half century following the Ottoman defeat by Timur, the Ottomans tried to recoup their losses in their provinces. In 1456, the Ottoman prefect of Amasya attacked Trabzon (Fig. 2, Trebizond) and captured about 2,000 people. The Trebizond emperor, John IV Komnenos, negotiated to keep his city and return the captives by paying a tribute to sultan Mehmed II. After 1461 (at the fall of Trabzon) and before 1486, the region lost a portion of its Muslim population as they were forcibly resettled in newly conquered Trabzon (Karatas (2011:42, 49, 51); Kaldellis (2014:313)).

In 1576, Amasya [apparently] had a population of 3,326 adult males of whom 77% were Muslim, 21% were Christian and 2% were Jews (Jennings 1976:37). Sadly, little information is available in English on Amasya for the 17th–18th centuries.

Hamilton (1842:365–366) describes his visit to Amasya in April 1836,

… we entered the town, winding through the narrow streets, admiring the remarkable caves in the rocks on the opposite side of the river, immediately under the castle … buildings, either in ruins or used as mosques, line the principal street through which we passed; many of the houses are built of stone, which, combined with its picturesque situation, gives the town an air of great superiority over most others in Turkey. The population is said to consist of from 3000 to 4000 Turkish houses, 750 Armenian and 100 or 150 Greek.

By 1862, a small Protestant congregation had gathered in Amasya in the face of the strongest [Orthodox Christian] opposition (The Missionary Herald May 1862:148). In 1864, it was reported that the unhealthiest part of the town was occupied by Christians, the Turks haven taken possession of the most agreeable quarters on both sides of the river (Van-Lennep 1870:85).

In 1912, the town of Amasya had around 15,000 (or 57%) Turks, 9,860 (or 37%) Armenians and around 1,300 (or 5%) Greeks, with two Greek churches/chapels and 206 Protestants. The county of Amasya had 24,844 Greeks (Greek Patriarchate data in Alexandris (1999); Kitromilides and Alexandris (1984–85)). Sadly, in 1913, a fire burnt one third of the town (Etyemez 2011).

In the late 19th and to pre-1915 Armenian Genocide, most adult Armenian men in Amasya were craftsmen including:

- Bakers. During the Armenian Genocide in 1915, Moriukian and one other Armenian baker were exempted deportation, as their work was considered essential.

- Ironsmiths and tinsmiths. In 1890, there were 30 ironsmith and five tinsmith workshops, all owned by Armenians.

- Tailors. In 1890, there were 20 tailor’s workshops, 15 were Armenian-owned and five were Greek-owned.

- Cobblers. In 1890, there were 50 cobbler’s workshops, 35 were owned by Armenians and 15 were owned by Greeks.

- Carpenters. In 1890, there were 10 carpenter’s workshops, all Armenian.

- Silk weavers. The Armenian Ipranosian brother’s silk factory became the largest in town.

- Tanners. Most tanners were Armenians.

- Potters. There were four potter’s workshops, three owned by Armenians and one by a Greek (www.houshamadyan.org/mapottomanempire/vilayet-of-sivas/amasya/economy/trades-and-commerce.html).

1915 Armenian Genocide

At the beginning of World War 1 (1914) the provincial district of Amasya had roughly 200,000 inhabitants, 64% Muslim Turks, 20% Greeks and 16% Armenians. The town of Amasya had 13,790 Armenians. The largest Armenian neighbourhood had the Cathedral of Our Lady, the bishopric, the Church of St James, the Armenian hospital, the Bartevian middle school, a Protestant Church, a Jesuit middle school and an Armenian Catholic church (Armenian Patriarchate data in Kévorkian (2011:275, 450)).

Around mid-March 1915, the first arrests of Armenians in Amasya by the Ottoman Turks occurred, targeting political leaders and teachers. On 18 May, other Armenian notables were killed. On 29 June, 360 Armenian men were taken from Amasya and killed. On 3 July, the deportations of Armenians began. The fifth (and last) convoy from Amasya comprised of around 1,000 Armenians—all males over eight years old were killed (Kévorkian 2011:450–451). In [mid] 1915, about half of the Armenian male population in Amasya were drafted to the Ottoman labour battalions (Morris and Ze’evi 2019:189).

1916 Greek Genocide

According to Germanos, the Greek Metropolitan of Amasya (1908–1922, which included Samsun):

On the 27th December [1916] eighty Greeks among the richest and most important inhabitants of Amassia [Amasya] were arrested … they were put into carts and conducted, like the vilest of criminals, through the mountains to the quarters of Kavza, whence they will be dispersed into different localities.

… the population of upper Amassia (Kadi Mahalessi) was ordered to assemble at the public-place. As soon as the inhabitants assembled, they were arrested and shut up in the barracks. The same thing was repeated in the village of Eliaz-keuy. The men were taken away unexpectedly, without a cent in their pockets; the old men and the sick were carried there by force brought by their relations; women who had just been confined with their newly-born babies were not even spared. Shortly after, at 12 o'clock Turkish time, all these unfortunate creatures, numbering about 4,000 with their wives and children, were marched off into the interior, without any food, and hardly properly dressed. Through the whole night long, small children and old men, the relatives of the mobilised Christians, either already dead or still working in the Labour Corps, were forced to march through mountains covered with snow. They looked like a flock of sheep being conducted to the slaughter-house.

On the 1st of January [1917], the police entered the Church in search of the remaining notables of the town of Amassia. Ten days later further proscriptions took place ... All the notables and rich merchants, about 300 in all, were expelled.

The peasants who sought refuge at Amassia are in the meantime being despatched by groups to the interior in a completely destitute condition, and we are in ignorance of their fate. We know, however, on good authority, that those expelled from Upper Amassia, after having crossed the mountains during the night arrived at Karak in a deplorable state, where they buried their dead. From Karak they were sent to Kavza (vilayet of Sivas) eighty kilometres distant from Amassia … Between Kazak and Kavza, many died on the way from hunger, cold or fatigue … they nevertheless were all deported to Tchoroum (vilayet of Angora) ...

‘January [1917] more arrests of merchants were made. They were expelled to the interior on the 13th. The whole country is reduced to a distressing situation and trembles with apprehension of greater evils to come.’

The Christians of Amassia, Tharchamba and Bafra, were expelled at different intervals and the torments undergone by the peasants were indescribable. The Military Governor … made out lists of the innocent Christians that were to be proscribed. Villages that had escaped ravage so far were now set on fire, and their inhabitants deported (Greek Patriarchate 1919:120–121).

According to the Trabzon Greek newspaper, Epohi, a deportation from Unye (on the Black Sea coast) took place in January 1917. It included approximately 60 Greek men who were forced to walk to Amasya where half died in the first 10 days (Ioannidou 2016).

Post World War I

In 1919, after World War I, Christian returnees to Amasya were forced back to ‘their places of deportation’ (Morris and Ze’evi 2019).

In June 1919, Mustafa Kemal met in Amasya with some of the men who were to join him in leading the national movement: Rauf Orbay, Ali Fuat Cebesoy and Refet Bele. They signed the Amasya Protocol, soon afterwards accepted also by Kazim Karabekir, which became more or less the first call for a national movement against the foreign occupations of Anatolia (Shaw and Shaw 2002:343–344).

On 4 June 1921, 1,041 Greeks from Samsun were the first convoy exiled to the interior where the Turks killed 701 Greeks. The remaining 339 Greeks were led to Amasya (Tsirkinidis 1999:189). The fourth mission of Greeks exiled from Samsun set out on 12 June with 580 men—351 of the old men were sent to Amasya (Hionides 1996:257). In 1921, Germanos, the Greek metropolitan of Amasya was condemned to death in absentia by the Turkish authorities (Kiminas 2009). In September, about 250 Greeks were hanged in Amasya (Morris and Ze’evi 2019). In the same month, following the Turkish victory at Sakarya [north-west Anatolia] against the mainland Greek army, operations against [Pontic] Greeks with women and children being dispatched to interior regions. According to Turkish Army records, 27,995 Greeks from Samsun, 14,000 from Amasya [county], 1,448 from Sivas, 4,910 from Ordu, 1,000 from Tokat, 571 from Çorum, 550 from Sinope and 8,500 from Giresun were relocated to Sivas, Tokat, Yozgat, Çorum and Karahisarisarki (Korucu and Daglioglu 2019:25).

Amasya Today

Amasya is a very picturesque town with many tourist sites like the tombs of the Pontic Mithradatic kings, the 12th century Fethiye Mosque, the 13th century Seljuk Burmali Mosque, the 15th century Bayezid Mosque (Plates 4–6), Amasya Castle, Hazeranlar mansion (built in 1865) and the Archaeological Museum. Many traditional Ottoman wooden houses have also been restored and used as boutique hotels, cafes, bars. Economic activities in the region include textiles and cement manufacture. However, most of its economy comes from agriculture such as apples, cherries, okra, onions, poppy seeds, lentils, beans and peaches, dairy products, eggs, sunflower oil and flour. The industrial products are relatively limited, but include lime, brick, marble, furniture, metal and plastic products (https://alchetron.com/Amasya).

Plate 5: Burmali Mosque, Amasya (Source)

Plate 6: Bayezid II Mosque (Source)

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

Alexandris A (1999) ‘The Greek census of Anatolia and Thrace (1910–1912): a contribution to Ottoman historical demography’,:45–76, in Gondicas D and Issawi C (eds) Ottoman Greeks in the age of nationalism: politics, economy, and society in the nineteenth century, The Darwin Press Inc, New Jersey, USA.

Dönmez EEN (2014) ‘The development of Turkish architecture in Amasya’, in Özdem F (ed) (2014):141–199.

Dönmez Ş (2014) ‘The ancient city of Amaseia’, in Özdem F (ed) (2014):9–27.

Dönmez Ş (2015) ‘Achaemenid presence at Oluz Höyük, north-central Anatolia’,:467–473, in Tsetskhladze GR, Avram A and Hargrave J (eds) The Danubian lands between the Black Sea, Aegean and Adriatic Seas (7th century BC – 10th century AD), Proceedings of the fifth International Congress on Black Sea antiquities, 17–21 September 2013, Belgrade, Archaeopress Archaeology, Oxford, England.

Dönmez Ş (2018) ‘Early Zoroastrianism at Oluz Höyük, north-central Anatolia’,:205–230, in Batmaz A, Bedianashvili G, Michalewicz A and Robinson A (eds) Context and Connection: Studies on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in Honour of Antonio Sagona, Peeters, Leuven, Belgium.

Dönmez Ş (2019) ‘The land of sacred fire: Amasya – Oluz Höyük’,:244–257, in Tsetskhladze GR and Atasoy S (eds) Settlement and Necropoleis of the Black Sea and its hinterland in antiquity, International Conference, 27–29 October 2017, Samsun, Turkey, Archaeopress Archaeology, Oxford, England.

Etyemez L (2011) Assessing the integration of historical stratification with the current context in multi-layered towns. Case study: Amasya, MSc thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey.

Greek Patriarchate (1919) Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey 1914–1918, (Greek Patriarchate in Constantinople), Hesperia Press, London.

Hamilton WJ (1842) Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia: with some account of their antiquities and geology, 1, (originally published by John Murray, London), reprinted 2009.

Hionides C (1996) The Greek Pontians of the Black Sea: Sinope, Amisos, Kotyora, Kerasus, Trapezus, Constantine Hionides, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Ioannidou T (2016) The holocaust of the Pontian Greeks: still an open wound, Theodora Ioannidou, (Place of publication not stated).

Jennings RC (1976) ‘Urban population in Anatolia in the sixteenth century: a study of Kayseri, Karaman, Amasya, Trabzon, and Erzurum’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 7(1):21–57.

Kaldellis A (2014) The histories: Laonikos Chalkokondyles, II (books 6–10), (translated into English by Kaldellis A), Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Karatas H (2011) The city as a historical actor: the urbanisation and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi order by the city of Amasya in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries’, PhD thesis, University of California, Berkeley, California.

Kévorkian R (2011) The Armenian genocide: a complete history, I.B. Tauris, London.

Kiminas D (2009) The Ecumenical Patriarchate: a history of its metropolitanates with annotated hierarch catalogs, Orthodox Christianity, I, The Borgo Press, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Kitromilides PM and Alexandris A (1984–85) ‘Ethnic survival, nationalism and forced migration: the historical demography of the Greek community of Asia Minor at the close of the Ottoman era’, Kentrou Mikrasiatikon Spoudon, [Centre for Asia Minor Studies], Athens, Bulletin, 5:9–44.

Koromila M (ed) (2002) The Greeks and the Black Sea: from the Bronze Age to the early 20th century, (translated into English by Doumas A and Fowden EK), The Panorama Cultural Society, Athens.

Korucu S and Daglioglu EC (2019) ‘Mapping out the Turkish documents on the unweaving of Greeks from the Black Sea (the Pontic genocide, 1919–1923)’,:7–27, in Shirinian GN (ed) The Greek genocide, 1913–1923: new perspectives, The Asia Minor and Pontos Hellenic Research Centre Inc., Chicago.

McEvedy C (1992) The new penguin atlas of ancient history, Penguin Books, London.

Morris B and Ze’evi D (2019) The thirty-year genocide: Turkey’s destruction of its Christian minorities 1894–1924, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, USA.

Nişanyan S and Nişanyan M (2001) Black Sea: a traveller’s handbook for northern Turkey, 3rd edn, Infognomon, Athens.

Özdem F (ed) (2014) Amasya: maid of the mountains (translated into English by Çakmak M), Yapi Kredi Yayinlari, Istanbul.

Roller DW (2020) Empire of the Black Sea: the rise and fall of the Mithridatic world, Oxford University Press, New York.

Shaw SJ and Shaw EK (2002) History of the Ottoman empire and modern Turkey: II: reform, revolution, and republic: the rise of modern Turkey, 1808-1975, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

Strabo The geography of Strabo (in Ancient Greek and translated in English by Jones HL, published 1969), Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann Ltd, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

The Missionary Herald (May 1862) LVIII(5), American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Boston.

Tsirkinidis H (1999) At last we uprooted them…: the genocide of Greeks of Pontos, Thrace and Asia Minor, through the French archives, (translated into English by Mavrantonis S), Kyriakidis Brothers SA, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Van-Lennep HJ (1870) Travels in little-known parts of Asia Minor, 1, John Murray, London (reprinted 2005 by Elibron Classics).

Zachariadou EA (1979) ‘Trebizond and the Turks (1352–1402)’, Twelfth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies: The Byzantine Black Sea, Birmingham England, 18–20 March 1978, Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], 35:333–358.