Platana, c. 1890s (Cacoulis brothers) Source

History of Platana (Akçaabat), Pontos1

Sam Topalidis (2025)

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist

Introduction

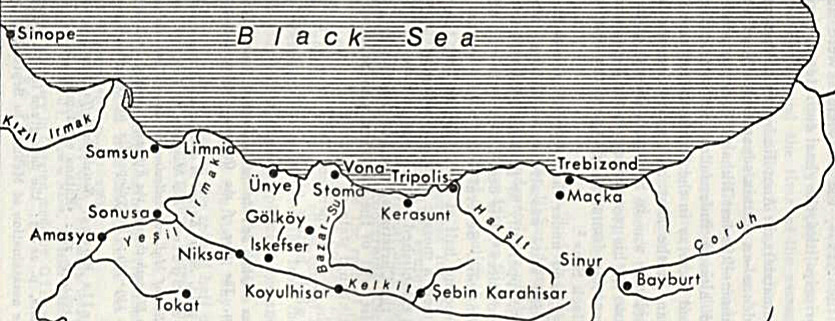

In the 20s AD, the Greek Geographer Strabo (book 12, part 3, 17) mentioned the settlement of Ermonassa, (which corresponds to Platana, current Akçaabat), which is 14 km west of Trabzon on the Black Sea coast in north-east Türkiye (Pontos) (Fig. 1). The first indication of the name Platana maybe in 910 AD, but from the early 14th century, ‘Platana’ appeared on nautical charts (Bryer and Winfield 1985:160). Evliya Çelebi, who visited the area in 1640, said the town was previously named Polathane. Later the town was renamed from Platana to Akçaabat by the Turks (www.turkey.org/tourism/trabzon/trabtown.htm).

Fig. 1: North-east corner of Anatolia, Pontos (Amasya to Trebizond = 330 km, Zachariadou (1979:335))

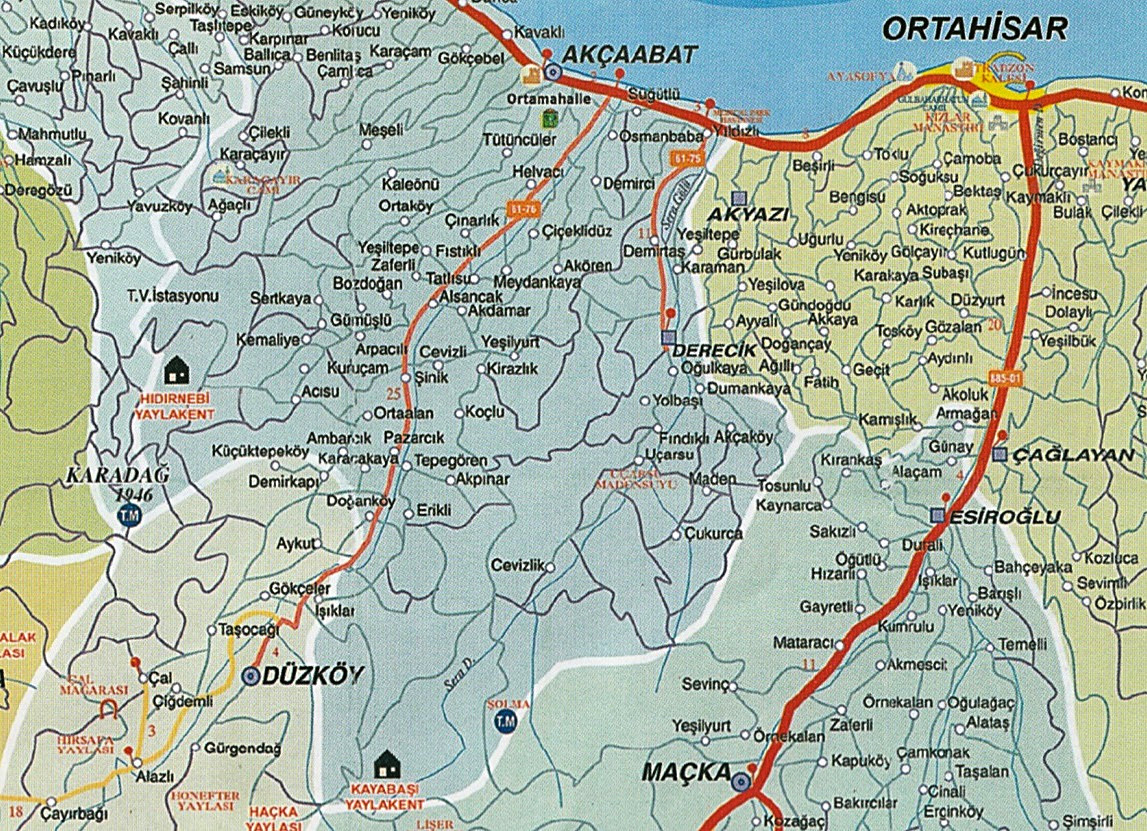

Platana has fertile land along the shore to the east where there are gently sloping hills and the fertile valley of the Kalenima River. South along the Kalenima River, the valley is about 25 km long, rising to about 1,250 m elevation (Fig. 2). There are no signs of defensive walls. Platana provided a source of food for Trabzon and is so well protected from the weather that it was used regularly as an alternative port to Trabzon in bad weather (Plate 1) (Bryer and Winfield 1985:10, 160).

Early History

It is unknown when humans first settled in Platana as there are no archaeological findings on the site. As the level of the Black Sea has risen up to 4 m since the 1st century AD, this rise may disguise its ancient foundations (Tsetskhladze 2007). Nevertheless, Platana’s early history must have been closely linked with nearby Trabzon.

Fig. 2: Turkish map of the Akçaabat area (Esiroğlu to Maçka = 12 km, Trabzon Tourism and Culture (n.d.))

Plate 1: Akçaabat (Source)

When Greeks settled at nearby Trabzon in the 6th century BC, there was probably a local indigenous population living there. Trabzon was a Greek colony of Sinope (400 km to the west, Fig. 1) which in turn, was a Greek colony of Miletos, on the Anatolian west coast. Xenophon did not mention Platana when his Greek army in 400 BC marched west of Trabzon along the Black Sea coast so we can surmise that Platana was colonised after 400 BC, probably from Trabzon or Sinope.

Pontos appears to have been included within the Persian empire from the 6th or 5th centuries BC and the Greek colonies may have been subject to it if only as vassals (Hewsen 2009). Although the army of Alexander the Great (reign 336–323 BC) defeated the Persians in Anatolia, the Greeks did not conquer the Black Sea coast (Şerifoğlu and Bakan 2015).

Mithradates and the Romans

After the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC), Mithradates I of Persian descent (reign 302–266 BC), established the kingdom of Pontos. Mithradates I and kings from the same family at times ruled over the area from Heraclea (west of Sinope) to Trabzon on the Black Sea coast until the reign of Mithradates VI (reign 120–63 BC). Mithradates I did not interfere with the body politic in the Greek cities of the coast which controlled the markets and shipping. Greek was the official language (Erciyas 2001). Mithradates VI [who expanded his empire around the Black Sea and into Anatolia]2 set his sights on Anatolia which was under Roman rule (Koromila 2002; Topalidis (2024b)). Mithradates VI was defeated by the Romans in 64 BC.

Pontos remained a kingdom allied with Rome until the 60s AD (Roller 2020). It was later absorbed into the Roman empire. In 257 AD, Trabzon [and most probably Platana] was sacked by the Goths (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

The Byzantine and the Komnenoi Emperors of Trebizond

After the sacking by the Goths, the Trabzon area had to wait till the 6th century for a revival of prosperity when Eastern Roman (Byzantine) emperor Justinian used the area as a supply base for his Armenian campaigns (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

In 1204, the same year crusaders from the Fourth Crusade conquered Constantinople, 22 year-old Alexios Komnenos and his younger brother David established the Komnenoi empire of Trebizond. They were the grandsons of Andronikos I Komnenos, Eastern Roman (Byzantine) emperor who was murdered in 1185. They fled Constantinople to the protection of their paternal aunt queen Tamar in Georgia in the turmoil that followed the murder of their grandfather (Miller 1926).

In 1214, the Seljuk Turks occupied Sinope and the Komnenos empire of Trebizond was then reduced to a narrow strip of land along the Black Sea coast to the east of Samsun (Miller 1926). Its wealth and influence far outstripped its size and population due to the trade via land and sea through Trabzon which was very profitable due to the collected taxes on goods entering and leaving the town to and from Asia (Nicol 1996:120).

Ottoman Control

Platana came under Ottoman Turk rule in 1461 when Ottoman sultan Mehmed II took control of Trabzon in the same year (Topalidis 2025b). At this time, the Trabzon/Platana area was overwhelmingly Christian Greek. It took till after 1580 before Platana’s population became mostly Muslim (Lowry (2009:169–170); Topalidis (2024a:161)).

From the late 17th century, timariots (military fiefs) and derebeys (valley lords) were effectively independent in many parts of Anatolia. The 14 Pontic derebey families which arose were primarily confined to one valley each. There was a derebey dynasty at Platana. To the non-Muslims the local derebey wars brought misery. The forceful destruction of the derebeys in Trabzon by the sultan occurred during 1812–1840 (Bryer 1969; 1970).

In 1836, Platana was believed to have had about 140 Greek and 200 Turkish houses (Hamilton 1842). In 1838, Trabzon’s trade was stimulated by trade agreements and then by the Crimean War (1853–1856) (Braude and Lewis 1982).

In 1901, Platana had 250 Greek houses and two Greek schools (Lazaridis 1988). In 1912, Platana county was around 70% Turkish with 36 churches with 28 priests and 6,327 Greeks (Maccas (1919); Alexandris (1999); (Soteriadis 1918)).

In 1914, the town of Platana had around 345 Greek families [around 1,725 Greeks, which included my father’s family], two Greek churches and two Greek schools (Chrysanthos 1933). In July, the Ottomans declared mobilisation of all ethnic groups with all men from 19 to 45 years of age being called to arms. The mobilisation would result in the land being uncultivated and the Trabzon [and probably Platana] tobacco crop not being sold because of the lack of workers (Fotiadis 2019). The Ottoman empire entered World War I in late October 1914. On 18 November the Russians laid 77 mines off Platana. Then on 8 February 1915, the Russian Fleet bombarded Trabzon (Nekrasov 1992).

1915 Armenian Genocide

In March 1915, the Ottoman Turks resolved to annihilate the Armenians (Genocide) in the Ottoman empire (Akçam 2019). In the same month, most Armenian soldiers in the Ottoman army had been disarmed and moved into labour battalions.

In Trabzon, a decree on 26 June, declared that Armenians would be exiled within five days. On 1 July, 300 young men were arrested placed on a ship anchored opposite Platana then thrown into the Black Sea (Kévorkian 2011:470).

Armenian deportations from Trabzon commenced in July (www.armenian-genocide.org/br-12-26-16-text.html). The deportation of Armenians also applied to 16 locations south and west of Trabzon, with an Armenian population of 3,517 in the county of Akçaabat. The men there were apparently killed in their villages by irregular bandits (Kévorkian 2011:480).

Of the ‘approximately’ 65,000 Armenians in the province of Trabzon, all but 15,000 were deported and subsequently killed. Some of these lucky 15,000 escaped deportation by hiding or were exempted because of their occupational expertise or just escaped from the deportation lines (Suakjian 1981).

Russian Occupation 1916–Early 1918

On 18 April 1916, Trabzon fell to Russian forces and then on 19 April, the Russians bombarded Platana from the sea. They landed around 5,000 soldiers in front of the Kalenima Creek, just east of Platana (www.akcaabat.bel.tr/fck-sayfalar.aspx?id=9). A day later, the Russian army entered Platana and proceeded west to the Harshit River near Tripolis (Topalidis 2025a) (Fig. 1).

Life in the Trabzon region during the Russian occupation (April 1916 to February 1918) was a difficult time for both the local population and the Russians with a prevalence of diseases, armed bandits and lack of food. Nevertheless, life was ‘relatively’ better for the Greeks under the Russians than in areas adjacent to the Russian occupied regions, where they were exiled under Ottoman guards, apparently for security reasons. This resulted in the deliberate death of many thousands of Greeks from starvation, disease and exposure (Topalidis and McCaskie 2018).

In early July 1916, Russian army officer, Mintslov, travelled to Platana by road along the shoreline from Trabzon. The gorges through which flowed small streams overgrown with trees were full of bivouacs, field hospitals of the vanguards, field kitchens and ordnance depots. Famine and cholera was evident in Platana (Mintslov 1923, 24 June [old calendar]).

Mintslov noted that the Russian Commander of Platana was trying to restore order but had treated the locals roughly. The town was mostly empty. In October, amidst hunger and disorder, Russian sailors there were reported to be thieves or dealers in contraband. Tobacco in warehouses in Platana was given to Russian soldiers who seemed to on-sell it in Batumi in Georgia. The sailors’ inefficiency was such that transports waited for unloading for up to three days. There was serious corruption in the Russian administration which confiscated food for distribution in the town (Mintslov 1923, 25 September [old calendar]).

According to Mintslov’s survey (published in November 1916), the town of Platana had 2,122 Greeks and Turks. In the 83 villages in the Platana area, there were 12,614 adults recorded of whom 68% were Turkish and 32% Greek. Tragically, the Armenian population was reported to be only 36 people. Of the adult Turkish population surveyed, only 35% were men. In contrast, of the Greek adult population surveyed, 41% were men (Table 1) (Mintslov 1916).

In early 1918, at the time of the Russian withdrawal from Anatolia, Platana had been plundered and burned after being raided by irregular Turkish troops and its inhabitants fled to Trabzon. Several murders had been committed (Fotiadis 2019:219). On 18 February 1918, Ottoman soldiers entered Platana.

The Turkish army in the Caucasus has begun an offensive. The attack was started before the expiration of the armistice. The Turks occupied Platana and paralysed the evacuation of the Caucasian corps … The Russians agreed … to evacuate Turkish territory and the withdrawal was evidently under way at the time of the Turkish attack (The New York Times, 24 February 1918).

Table 1: Adult population in the Platana area 1916*

| Ethnicity | Adult males | Adult females | Total | % ethnicity |

| Ottoman Turks | 3,030 | 5,510 | 8,540 | 68 |

| Greeks | 1,670 | 2,404 | 4,074 | 32 |

| Total | 4,700 | 7,914 | 12,614 | 100 |

* Included 83 villages (Mintslov 1916:iii)

1919–1923

In 1919, Armenians who returned to Platana after World War I were murdered shortly after their arrival (Morris and Ze’evi 2019:311). Charitable organisations in Anatolia tried to assist refugees returning to their homes. In 1919, American doctor Blanche Norton worked in the Trabzon clinics run by the Greek Red Cross and the Turkish Red Crescent and once a week, she also ran a clinic at Platana (www.greek-genocide.net/index.php).

In May 1919, the Greek army landed at Smyrna (west coast of Anatolia). During the ensuing Greco-Turkish War in western Anatolia (1919–1922), the Turks regarded the Greeks throughout Anatolia, especially those in Pontos and near the front lines, as potential fifth columnists who would aid the Greek army (Morris and Ze’evi 2019). This attitude would have disastrous effects on Greeks in Anatolia.

In March 1922, the British High Commissioner at Istanbul reported that the Greek males aged above 15 years from Trabzon and the adjoining areas were deported to join the Turkish labour battalions at Erzurum, Kars and Sarikamish (Tsirkinidis 1999). In mid-December, it was noted that the Orthodox priests in the area of Platana had been slaughtered and the authorities refused to punish the perpetrators (Fotiadis 2019).

In January 1923, most of the Orthodox Christian families who still lived in Trabzon were told they must leave and gather near the harbour bringing only what they could carry (Clark 2006). By 1924 about 1.4 million of the surviving Anatolian Greeks had been forcibly uprooted and settled in Greece as part of the compulsory exchange of Christian and Muslim populations in accordance with the settlement at the 1923 Conference of Lausanne. Many thousands of Greeks had previously left Anatolia with the departing Russian army in 1918.

St Michael and the Incorporeal Saints Churches

There were two Byzantine churches in Platana, one dedicated to St Michael and the other to the Incorporeal Saints (Freely 1996). Hamilton (1842:246–247) visited the old Greek Church of St Michael in 1836:

... within are some curious old paintings on the screen before the alter, behind which four small marble columns rest on a low wall of the same material, and support a rude soffit. On the outside the windows and niches, several of which are false, are in rich Byzantine taste, decorated with several rows of an elegant beading or border. The priest was summoning his congregation to church on my arrival; and as the Greeks are not allowed the use of bells, they supply the want of them by a piece of wood suspended from a tree [semantron], which is struck like a drum by the priest …

On the beach were several boats from Trebizond taking in lime, which is burnt in kilns near the spot where the shelly lime-stone, which appears to be of rare occurrence on this coast, is found [Plate 2].

Plate 2: Platana, 1890s (Cacoulis brothers, Source

The former St Michael Greek Orthodox Church (Plate 3) is located up a hill in Ortamahalle. The church is likely to have been built in the 13–14th century and was restored and extended in 1846 (Ballance 1960). Very close to the church was a well-constructed Greek school built in 1893 which is now a Turkish Primary school.

The church was abandoned in 1923 when the Greeks were forced out of Anatolia. In 1929, the church was still abandoned and in a very poor state (Talbot Rice 1929–1930).

The exterior of the church was built using light-coloured stone with various shades of pinkish-brown, green and yellow. In 1958, it was used as a residence. A former Greek church [Incorporeal Saints] was just south of the former St Michael Greek church. In 1958, it was still in a fair state of repair and was used to house cows and hens. The rounded apse with parallel-side windows, the barrel-vaulted naos, the coarse masonry and use of brick for window arches were typical of medieval work in this area (Ballance 1960). Winfield and Wainwright (1962) state that this church had just been pulled down when they visited the site in 1961.

Plate 3: St Michael Church, now Ortamahalle Museum, Akçaabat (2021, Source)

In 2020, renovations of the former St Michael Church were completed and is now the Ortamahalle Museum. The mosaic floor has been reconstructed and covered by what seems to be clear perspex (www.dailysabah.com/arts/700-year-old-church-in-ne-turkey-converted-into-museum/news).

Akçaabat Today

Akçaabat’s population today is estimated to be nearly 83,000 (2022 estimate, www.citypopulation.de/en/turkey/trabzon/TR90101__akçaabat/). It has a close relationship with nearby Trabzon. The attractive traditional houses in Ortamahalle are located on an east facing slope (Plate 4). The Toki mass housing project is 6 km away from the district centre with 22 blocks in rows of 4–5 buildings. These buildings [examples of poor planning] are exposed to the north-west winds and poorly positioned to capture sunshine (Vural et al. 2016:69). There is no railway in Akçaabat.

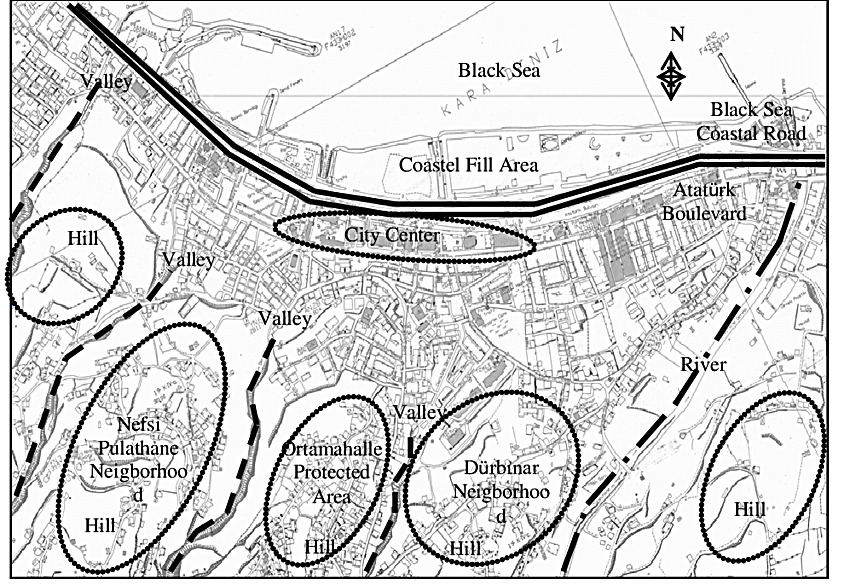

Between 1995 and 2005 there was a reconstruction of the town’s coastline. The steep topography has created an east-west settlement. The historic neighbourhoods of the town where the topography is often divided by valleys, Çolakli, Nefsipulathane, Ortamahalle and Dürbinar are separated by streams (Fig. 3) (Akin 2020:98).

Plate 4: Historic houses in Ortamahalle, Akçaabat, 2015 (Source)

Fig. 3: Akçaabat (Turk and Bayram 2012:188)

There are wide plains on the mountains at around 1,800–1,900 m. Festivals are held in many of the highlands during the summer months (Plate 5). In addition, 4 km from the coast on the Yıldızlı stream, there is the Sera Lake, which was formed after a landslide in 1950 and is now a recreation area (www.akcaabat.bel.tr/fck-sayfalar.aspx?id=9).

Fishing, hazelnuts, olive cultivation to a lesser extent, tourism and animal husbandry are the main sources of income in Akçaabat (www.akcaabat.bel.tr/fck-sayfalar.aspx?id=10).

Plate 5: Plateau festival, Akçaabat (Source)

Plate 5: Plateau festival, Akçaabat (Source)

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

1. Sadly, there is a lack of reliable information in English on Platana/Akçaabat.

2. Words within square brackets ‘[ ]’ within a reference are the author’s words.

Sources

Akçam T (2019) ‘When was the decision to annihilate the Armenians taken?’ Journal of Genocide Research, 21(4):457–480.

Akin ES (2020) ‘Examining the urban identity of Akçaabat’, ACU Orman Fak Derg (Artvin Coruh University Journal of Forestry Faculty), 21(1):93–109.

Alexandris A (1999) ‘The Greek census of Anatolia and Thrace (1910–1912): a contribution to Ottoman historical demography’ in Ottoman Greeks in the age of nationalism: politics, economy, and society in the nineteenth century,:45–76, in Gondicas D and Issawi C (eds) Ottoman Greeks in the age of nationalism: politics, economy, and society in the nineteenth century, The Darwin Press Inc, New Jersey, USA.

Ballance S (1960) ‘The Byzantine churches of Trebizond’, Anatolian Studies, x:141–175.

Braude B and Lewis B (1982) Christians and Jews in the Ottoman empire: the functioning of a plural society: the central lands, 1, Holmes & Meier, New York.

Bryer A (1969) ‘The last Laz risings and the downfall of the Pontic derebeys, 1812–1840’, Bedi Kartlisa, Revue de Kartvelologie, XXVI:191–210, Paris.

Bryer A (1970) ‘The Tourkokratia in the Pontos: some problems and preliminary conclusions’, Neo-Hellenika, 1:30–54.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I & II, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Chrysanthos (1933) ‘H Eκκλησια Τραπεζουντος’, (in Katharevousa Greek), [The church of Trabzon] Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], iv-v, Athens.

Clark B (2006) Twice a stranger: how mass expulsion forged modern Greece and Turkey, Granta Books, London.

Erciyas DBA (2001) ‘Studies in the archaeology of Hellenistic Pontus: the settlements, monuments, and coinage of Mithradates VI and his predecessors’, PhD thesis, University of Cincinnati, USA.

Fotiadis KE (2019) The genocide of the Pontian Greeks, (translator into English not stated), KE Fotiadis, (place of publication not stated).

Freely J (1996) The Redhouse guide to the Black Sea coast of Turkey, Redhouse Press, Istanbul.

Hamilton WJ (1842) Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia: with some account of their antiquities and geology, 1, (originally published by John Murray, London), reprinted 2009.

Hewsen RH (2009) ‘Armenians on the Black Sea: the province of Trebizond’,:37–65, in Hovannisian RG (ed) Armenian Pontus: the Trebizond-Black Sea communities, Mazda Publishers Inc, Costa Mesa, California.

Kévorkian R (2011) The Armenian genocide: a complete history, I.B. Tauris, London.

Koromila M (2002) The Greeks and the Black Sea: from the Bronze Age to the early 20th century, new and enlarged edition, (translated from Greek into English by A Doumas and EK Fowden), The Panorama Cultural Society, Athens.

Lazaridis D (1988) Στατιστικοι πινακες της εκπαιδεύσεως των Eλληνων στον Ποντο 1821–1922 (in Greek), [Statistical list of Greek schools in the Pontos 1821–1922], Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], 16, Epitropi Pontiakon Meleton, [The Committee for Pontic Studies] Athens.

Lowry HW (2009) The Islamization & Turkification of the city of Trabzon (Trebizond), 1461–1583, The Isis Press, Istanbul.

Maccas L (1919) L'hellenisme de l'Asie Mineure, [Hellenism in Asia Minor, in French], Nancy, Paris.

Miller W (1926) Trebizond: the last Greek empire, The MacMillan Co, London.

Mintslov SR (1916) Statisticheskie ocherki Trapezondskogo ukreplennogo raiona, (in Russian) [Statistical report of Trabzon region], (unpublished translation by R McCaskie), Trabzon, Turkey.

Mintslov SR (1923) Trapezondskaia epopeia, (in Russian) [Russian accounts of Trabzon], (unpublished translation by R McCaskie), Sibirskoe Knigoizdatel’stvo, Berlin.

Morris B and Ze’evi D (2019) The thirty-year genocide: Turkey’s destruction of its Christian minorities 1894–1924, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Nekrasov G (1992) North of Gallipoli: the Black Sea fleet at war 1914-1917, East European Monographs, CCCXLIII, Columbia University Press, New York.

Nicol DM (1996) The Byzantine lady: ten portraits, 1250–1500, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

Roller DW (2020) Empire of the Black Sea: the rise and fall of the Mithridatic world, Oxford University Press, New York.

Soteriadis G (1918) An ethnological map: illustrating Hellenism in the Balkan peninsula and Asia Minor, Edward Stanford LTD, London.

Şerifoğlu TE and Bakan C (2015) ‘The Cide-Şenpazar region during the Hellenistic period (325/300–1 BC)’,:246–259, in Düring BS and Glatz C (eds) Kinetic landscapes: the Cide archaeological project: surveying the Turkish western Black Sea region, De Gruyter Open, Warsaw, Poland.

Strabo The Geography of Strabo, in Greek with an English translation by HL Jones (1928), William Heinemann, London.

Suakjian KY (1981) Genocide in Trebizond: a case study of Armeno-Turkish relations during the First World War, PhD thesis, University of Nebraska, Nebraska, USA.

Talbot Rice D (1929–1930) ‘Notice on some religious buildings in the city and vilayet of Trebizond’, Byzantion: revue Internationale des Etudes Byzantines, 5:47–81, 438–440.

The New York Times (24 February 1918) ‘Turks break truce and attack Russians – occupy Platana, on Black Sea, before the armistice with Petrograd expires’.

Topalidis S (2024a) Greek Pontos, Kyriakidis Bros, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Topalidis S (2024b) ‘Mithradates VI, king of Pontos: murderer or liberator or both?, at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/896-mithradates-vi-king-of-pontos

Topalidis S (2025a) ‘History of Tirebolu (Tripolis), Pontos’, at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/909-history-of-tirebolu

Topalidis S (2025b) ‘The fall of the Komnenoi Trebizond empire, 1461’, at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/912-the-fall-of-the-komnenoi-trebizond-empire-1461

Topalidis S and McCaskie R (2018) ‘Life during the Russian occupation of Trabzon during WW1’, at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/647-life-during-the-russian-occupation-of-trabzon

Trabzon Tourism and Culture (n.d.) Home of Trabzon tourist map, [in Turkish] Trabzon, Türkiye.

Tsetskhladze GR (2007) ‘Greeks and locals in the southern Black Sea littoral: a re-examination’,:160–195, in Herman G and Shatzman I (eds) Greeks between east and west: essays in Greek literature and history in memory of David Asheri, The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Jerusalem.

Tsirkinidis H (1999) At last we uprooted them…: the genocide of Greeks of Pontos, Thrace and Asia Minor, through the French archives, (translated into English by S Mavrantonis), Kyriakidis Brothers SA, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Turk YA and Bayram ZY (2012) ‘Timescape of city: Akçaabat’,:183–198, in Sahin Y, Aslanturk O and Bilgili MY (eds) (2012) 2nd International Congress on Urban and Environmental Issues and Policies, Papers and Proceedings of Congress, 4–6 May 2012, Trabzon, Turkey.

Vural N, Engin N and Vural S (2016) ‘The applicability of ecological lessons learnt from traditional houses to mass housing projects: a case study of Akçaabat, Trabzon/Turkey’, Journal of Art and Design, 4(2):66–75.

Winfield D and Wainwright J (1962) ‘Some Byzantine churches from the Pontus’, Anatolian Studies 12:131–161.

Zachariadou EA (1979) ‘Trebizond and the Turks (1352–1402)’, Twelfth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies: The Byzantine Black Sea, Birmingham England, 18–20 March 1978, Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], 35:333–358.