Pontian Greek ladies and children of Trabzon, circa early 20th century.

After the fall of Byzantium in 1453, Ottoman Greeks (Orthodox Christians) lived in the Ottoman Empire with the Ecumenical Patriarchate at Constantinople as their spiritual head. The Christians and Jews were referred to as the ahl-al-kitab or the People of Revealed Books or Scripture, and the Sacred Law of Islam provided them protection. Pagans and polytheists had to accept Islam or perish. The term dhimmis or tolerated infidel was used to describe the Christians and Jews.

Dhimmis coming from the word dhimma was the contract by which the Christians were regulated within the domain of Islam. Within the contract, Muslim rulers allowed the dhimmis to exercise their own religion and guaranteed their lives, in return for a special poll tax which they had to pay, the jizya or haraç. They were also bound by regulations which were aimed at reflecting their inferior status within the Empire. The Greeks of the Ottoman Empire were referred to as Rumlar or Romans. The Greeks who were living in independent Greece or Yunanistan were referred to as Yunanlar or Ionians.

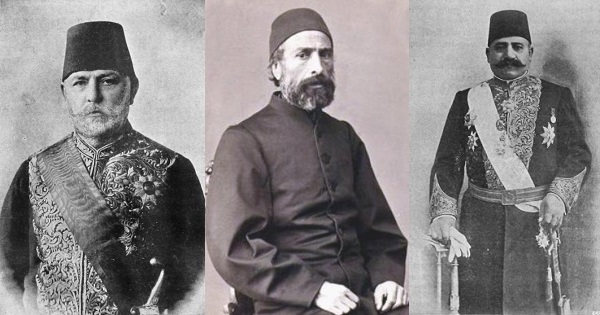

Pictured from left: Constantine Anthopoulos (1835-1902) otherwise known as Kostaki Antopulos Paşa, a high-ranking Greek Dignitary of the Ottoman Empire. Middle: İbrahim Edhem Pasha (1819 – 1893) an Ottoman statesman of Greek origin who held the office of Grand Vizier between 1877 and 1878. Right: Avraam Vaporidis Efendi (1855-1911) otherwise known as Avraam Vaporidi Efendi, an author, scholar and high-ranking Greek Dignitary of the Ottoman Empire.

Legally recognized religious communities were called millets. Apart from the Muslim millet, millets also existed for the Greek Orthodox (also called the Rum millet), as well as the Jewish, Armenian and Syrian Orthodox millets. Whilst religious institutions within the millet were exempt from tax, each millet was required to pay tax to the imperial government. To some degree, the millet system allowed religious communities to be self governing. As the Ottoman administration gradually weakened throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, millets were becoming more and more responsible for their own judicial administration, some even establishing their own prisons.

The timar or fief system was part of the Ottoman agrarian system and was a type of military landholding. Provinces were divided into fiefs according to their size. A fief was the smallest unit of land, the largest unit being a hâss. Fiefs were allocated to elite cavalrymen (sipahi) who were entitled to collect and keep the income of the land in return for providing military service to the Empire in times of war. A timariot (or timar holder) on the other hand was an irregular cavalryman of the Ottoman Army and collected money from the peasantry in the same way. The system originated in pre-Ottoman times, but came into formal effect in the 14th century. By the start of the 17th century, the timar system declined and ended.

Provinces in the Ottoman Empire were known as eyâlets, but beginning in 1864, they were gradually restructured into smaller vilâyets. Most of these were also subdivided into sanjaks.

The vilayet of Trebizond. Cuinet (1890).

In the second half of the 19th century, the main area of Pontus was made of the vilayet of Trebizond but also comprised the adjoining vilayets of Kastamonu, Sivas and Erzerum. The northern border started to the west of Sinope and stretched as far east as the Russo-Turkish border. The southern border began from Inepolis and ran through Amaseia, Tokat, Nikopolis, Argyroupolis, Paipurt, the Soganlou Dag mountain range and ended at the Russo-Turkish border.

The region of Pontus was made up of 6 ecclesiastical provinces, namely Trapezunta, Rodopoleos, Chaldia, Neocaisarea, Amaseia and Kolonia.

References

- The Eastern Question: The Last Phase. Harry J.Psomiades.

- The social origins of the modern Middle East. Haim Gerber