Historically known as Trapezus, Trebizond and Trapezunda by Greeks, the city of Trabzon in north-eastern Turkey boasts a rich Hellenic past. It was founded by Greeks in the 8th century BC and existed as a colony of Sinope. Today the city is named Trabzon as is the province it is located in. Trapezunda rose to be an important city in terms of trade during the time of the Roman Empire; its position allowing it to benefit from trade between Persia and the European provinces of Rome.

The church of Saint Sophia, Trebizond

In 1665, a horde of fanatic Turks raided the district of St. Phillip forcing the Greeks out of their homes and subsequently taking over the church which they turned into a mosque. The Metropolitan (priest) managed to survive the rage of the Turks and fled to the church of St Gregory of Nyssa which subsequently became the new Metropolitan church of Trebizond. The remaining Greeks of St. Phillip fled to the neighbouring region of Tonya where they were later forced into Islam, a common practice during Ottoman times. During this period, wealthy and influential Greek families of Trebizond such as the Mourouzis, Ypsilantis and Rizoi families as well as others, fled to neighbouring Russia or Constantinople.3

This general persecution of the Christian Greek population of Trebizond was to continue until the Tanzimat reforms which were implemented during the period 1839-1876. A series of reforms in 1856 known as the Hatt-ı Hümayun promised full legal equality for citizens of all religions. The Greeks were finally able to conduct their day to day lives as equals, and in the coming decades benefited from it.

The Trabzon Museum, built in the early 1900's by Greek banker Konstantinos Theofylaktos.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Greeks of Pontus owned buildings and assets of enormous wealth. They owned 37 formal philanthropic and cultural foundations, 1047 schools (primary and pre-secondary), 10 secondary schools (comprising 1236 teachers and professors, and 75,953 students), 22 monasteries and 1139 churches under the direction of 1459 priests.4 Much of this wealth was centered around Trebizond.

According to figures collected by the British consul, the volume of shipping clearing the port of Trabzon rose from an average 15,225 tons a year in the early 1830's to 61,664 tons a year twenty years later. 177,861 tons a year in the early 1870's and 483,732 tons a year in the early 1890's. By 1882 the steamships of 5 different companies called weekly at Trabzon.5 The Greeks benefited from this increase in trade and by the early 1900's had increased their wealth considerably. Of the 5 banks in Trebizond in operation, 3 of them were owned by members of the Greek community: the Bank of K.Theofylaktos, the Bank of Kapagiannidis and the Bank of Fostiropoulos. The 4th was a branch of the Ottoman bank and the 5th was a branch of the Bank of Athens.6

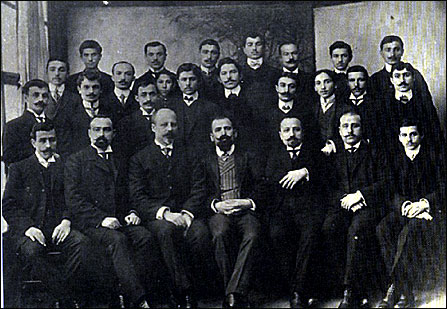

Employees of a bank in Pontus, 1915

The Greeks were also influential in public life. They took part in political administration, judicature, finance, agriculture and technical works. In the courts of first instance, appeal and of commerce there was one Greek in each section. In finance they worked in tax collection, the estimates committee, tobacco monopoly, Ottoman and Agricultural Bank branches, and public debt administration. In education they were sometimes employed on the education committee and in secondary schools. They were important contributors to engineering and public works as engineers and the postal and telegraphic service as operators.7

The Greeks of Trebizond became renowned for building numerous churches, some of which are still standing today. Saint Sophia which was built in the 13th century is perhaps the most notable Greek Orthodox church. The Greeks also built numerous buildings in the city. The Ataurk Kiosk is in fact a building built in 1890 by wealthy Greek banker Konstantinos Kapagiannidis. The Trabzon Museum was built in the early 1900's by banker Kostantinos Theofylaktos. Another notable building is the Trapezunta Tuition Center (Frontistorion Trapezuntas) which was founded in 1682.

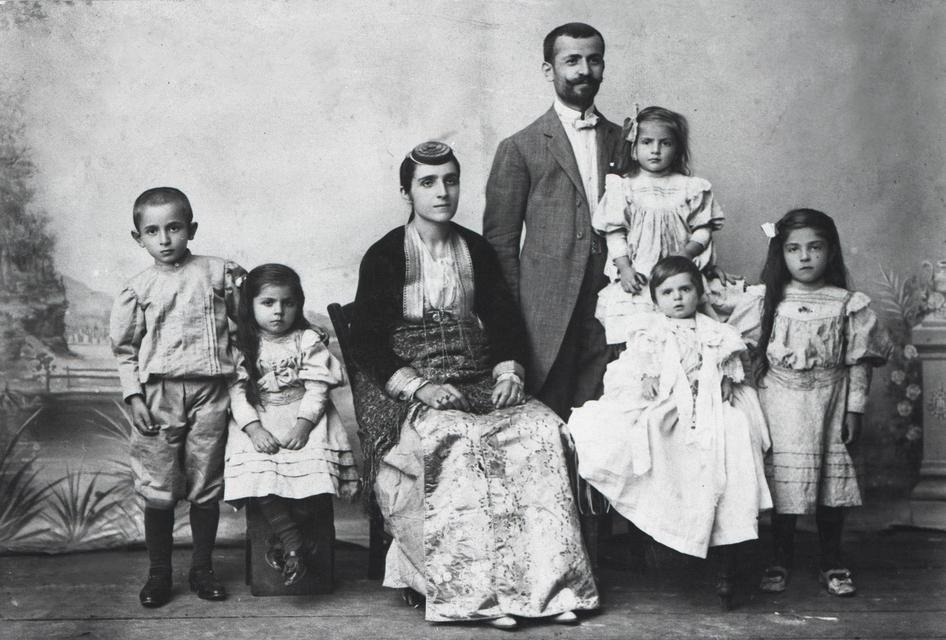

Pontic Greek family in Kerasus (today Giresun), 1910. Source

According to Brant, the British consul at Erzurum, the population of Trebizond in 1835 was between 25,000 and 30,000 inhabitants, 3,500 to 4,000 of whom were Greek (~13% Greeks). The Muslims lived within the walled part of the town while the Christian part of the population lived outside of the walls.8 In the next 50 years, the number of Greeks living in the town increased considerably. According to D.I Oeconomides, at the beginning of the 20th century, Trebizond consisted of 50,000 people, 15,000 of whom were Greek (30% Greeks).9 By 1910, the number of Greeks living in the province of Trebizond exceeded 200,000.

By the early part of the 20th century, the Greeks of Trebizond made up a part of the bourgeois. In many photos of the time, they were seen dressed lavishly; the men in tailor-made suits and the women in rich silk dresses. They were often seen traveling by carriage to their villas situated on the outskirts of the town.

The persecution of the Greeks of Trebizond followed the persecution of the Armenian population of the town. The Greeks of Trebizond were sent on death marches into the mountains of Bitlis around 1919-1920, most perishing never to return. The remainder were forcefully sent to Greece as part of the Exchange of Populations between Greece and Turkey (1923), thus ending an almost three thousand year presence of Hellenism in the region.

The daughters of Panayioti Kakoulidis, grandfather of Athena Makridou-Kalliga (seated: Sophia Tsouliadou, Evanthea Neofytou, Froso Velissaridou, standing: Artemisia Makridou, Evdokia Michailidou, Sevasti Thomaidou and Cornelia Kalpaxidou). Source

Today the region has a sizable community of Greek-speaking Muslims, most of whom are originally from the vicinity of Tonya and Of. They speak the Pontic dialect, a dialect which is based on the ancient Greek.

As Michael Meeker writes: "The Turks who settled along the Black Sea Coast of Asia Minor first encountered for the most part a Greek-speaking, not a Lazi speaking population, and the way of life which these Turks adopted was learned from Greek speakers."10

So while the majority of Greeks were exterminated or forced out, Greek presence can still be felt in Trebizond today through its historic churches and buildings and the quasi Greek-Turkish culture which is evident through its people.

References

1. Labour Migration and Economic Conditions in Nineteenth Century Anatolia. Christopher Clay.Middle Eastern Studies. Vol 34, No.4. Turkey before and after Ataturk: Internal And External affairs. (Oct.,1998), pp1-32

2. The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism

3. The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism

4. The Greeks in the Black Sea. M.Koromila, pp 282-3

5. Labour Migration and Economic Conditions in Nineteenth-Century Anatolia

Author(s):Christopher Clay. Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 34, No. 4, Turkey before and after Atatürk: Internal and External Affairs (Oct., 1998), p. 7

6. The Greeks in the Black Sea. M.Koromila, pp.282-3

7. Armenians in the service of the Ottoman Empire, 1860-1908 By Mesrob K. Krikorian page 51

8. Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Brittain) Vol 25-26 p 180

9. The Encyclopedia of Pontian Hellenism

10. The Black Sea Turks: Some Aspects of Their Ethnic and Cultural Background. International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Oct., 1971), p 332