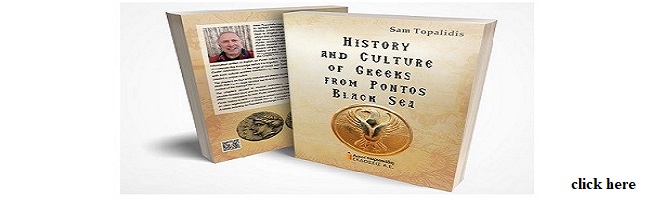

Figure 1: Sinope silver drachm coin showing a spread-winged eagle with its head turned, reverse is a head of a nymph (4th–3rd centuries BC), <Source>.

by Sam Topalidis, Pontic Historian 2017.

Historically, the single- and double-headed eagle emblems signified major symbols of power. Their origin is from Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium BC and later in the 2nd millennium BC they were used by the Hittites in Anatolia. The eagle symbol was used by many people including the Ancient Greeks and Romans. Later again, the single- and double-headed eagle symbols were used by the Seljuk Turks (and other Turkmen) and the Byzantine Palaiologan dynasty (1261–1453) as their emblems.

In Pontos (north-eastern Anatolia adjacent to the Black Sea), ancient Greek coins were struck at Sinope ca. 4th century BC with the symbol of the eagle (Figures 1 and2). Much later, both the single- and double-headed eagle symbols were used by the Komnenoi emperors of the small Byzantine empire of Trebizond (1204–1461).

Today, Pontic Greeks (Greeks with roots from Pontos) revere the single-headed spread-winged eagle with its head turned, as their distinguishing emblem.

Origins of the Single- and Double-headed Eagle Symbol

Eagles and double-headed deities are commonly found in Mesopotamian religious icons (Deedes 1935). (Note 1.) The double-headed eagle symbol probably has its origins in Mesopotamia from the 4th millennium BC as the lion-headed bird-bodied god Anzu. This bird may have transformed to a double-headed eagle in Assyrian culture after the Sumerians. This symbol came to Anatolia by Assyrian merchants (Himmetoğlu 2017).

The Hittite site of Alaca Hüyük in north-central Anatolia [in the current Turkish province of Çorum] dated to the 14th–13th centuries BC displays a double-headed spread-winged eagle on the Sphinx Gate clutching two rabbits or hares (Figure 3). The single- and double-headed eagles also appear in seals throughout Hittite history (Alexander 1989).

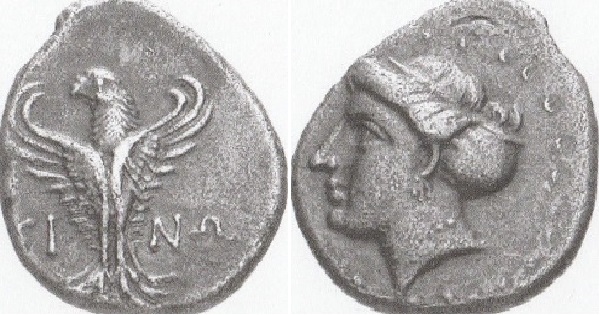

Figure 2: Sinope silver drachm coin showing an eagle on the back of a dolphin (ca. 330–300 BC), <Source>.

In Pontos ca. 4th century BC, the eagle was represented on Greek coins issued from Sinope (some examples are Figures 1 and 2). In ancient Greece the eagle (the king of birds) was associated with the god Zeus, but the eagle was not an embodiment of him (Mylonas 1946). (Note 2.) The regal and divine status of the eagle in Greek thought was transmitted into Roman mythology (Hayes 2014).

There are instances pointing to the early association of the eagle with light. The eagle was also known in Greece and Rome as the bird of divination. We have here the double nature of the eagle as the bird of light and the bird of magic common to many civilisations (Wittkower 1939).

A symbol of the Roman god Jupiter, the eagle, served as the chief military standard of the Roman legions from 104 AD (Keppie 1998). Jupiter’s eagle-headed sceptre was displayed on Roman imperial coins and then on Byzantine coins struck between the late 6th and early 8th centuries (Angelov and Herrin 2012).

In the 12th and 13th centuries the double-headed eagle was used by the Seljuk Turks and the Turkmen princes of Anatolia and the Turkmen Zangid princes of Iraq as their standard (Androudis 2015). Single- or double-headed eagles were placed above the gates of the Seljuk Turk Konya wall (1221) in Anatolia. The double-headed eagle was also placed on the western gate of the Great Mosque of Divriği [built in 1228–29 in the current Turkish province of Sivas] (Peker 1999).

Figure 3: Double-headed eagle at the Hittite site of Alaca Hüyük, north-central Anatolia (Chariton 2008, p. 18).

Single- and Double-headed Eagle Symbols in the Byzantine Empire and Pontos

Examples of the use of the eagle symbol, single- or double-headed, are described in the Byzantine empire including the small Komnenoi Byzantine empire at Trebizond (modern Trabzon on the Black Sea) in Pontos.

Isaac I Komnenos

The Roman imperial eagle was single-headed, but in 1057 the Byzantine emperor Isaac Komnenos adopted the two-headed eagle [this point is contentious] (Ambrose 2013).

The following Komnenoi emperors of the Byzantine empire of Trebizond have official portraits or descriptions of their official robes adorned with or without eagles.

Manuel I Komnenos (reign 1238–63)

The double-headed eagle was not a symbol of Trebizond in the 13th century, when a single-headed eagle was twice displayed in the St Sophia church, Trabzon. (There was also an inscription of emperor Alexios II (reign 1297–1330) above a single eagle on the western wall of the lower city in Trabzon.) The double-headed eagle was a common Seljuk and Turkmen symbol [at this time] (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

In 1850, historian George Finlay observed the following in the St Sophia church (which had been converted into a mosque):

I was fortunate enough to find a full-length figure of the emperor Manuel … to the right of the door used as the entry to the mosque. The emperor is without a crown, wearing only a band on his head ornamented with a double row of pearls; his robes are adorned on both sides, down the front, with two rows of single-headed eagles on circular medallions, about three inches in diameter … (Finlay 1851, p. 394).

The portrait of Manuel I is now lost and Finlay did not provide a drawing of the portrait (Note 3). The eagles at the St Sophia church are only general depictions of power. The ubiquity of eagles in Anatolian art in the 13th century prevents any specific association of the eagles at St Sophia with the Komnenoi emperors. The eagle is not a heraldic symbol (at this time) as eagles (both single- and double-headed) are also associated with the Palaiologan family in Constantinople and evidence about the adoption by families of heraldic emblems in this period is contentious (Eastmond 2004).

John II Komnenos (reign 1280–85 & 1285–97)

In 1282, emperor John II Komnenos went to Constantinople to wed Eudokia, daughter of the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos. John II was asked by the Constantinople envoys to remove his imperial red boots and wear inferior black boots. It had been agreed that the Byzantine emperor would give him, as soon as he became his son-in-law, the inferior rank and symbols of a Despot (Note 4). John II was forced to renounce his claim to the title ‘Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans’ (Miller 1926).

Finlay (1851) believed the robes that John II wore were ‘probably’ adorned with single-headed eagles. We don’t know exactly what robes he wore, but it would have been consistent with robes appropriate for a Despot of the Byzantine Court.

In 1850, Finlay noted in the church of St Gregory of Nyssa in Trabzon that:

On the right wall of the porch nearest the church door is the figure of an empress with double-headed eagles embroidered on her robes, the centre figure is that of an emperor whose robes have single headed eagles. This induces me to conjecture that the emperor is John II 1280–1297 who married Eudokia the daughter of Michael VIII … (Bryer and Winfield 1985, p. 227).

However, this identification is not conclusive. There seems to have been a Greek tradition that Eudokia founded St Gregory of Nyssa. (The church was rebuilt in 1863 and the portraits are now lost.) The belief that the ‘special emblem’ of the Komnenoi emperors as the single-headed eagle may be a Trabzon myth begun by the historian Fallmerayer. [Fallmerayer produced his book History of the empire of Trebizond in German in 1827.] Palaiologan and Kantakouzene brides sported double-headed eagles on their robes, but it is unlikely that John II would deliberately wear inferior single-headed eagles on his robes in an imperial portrait (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

Alexios III Komnenos (reign 1349–90)

Eagle emblems used by the Komnenoi include Theodora Kantakouzene, wife of Alexios III Komnenos [a relative of the Byzantine emperor at Constantinople] wearing a gold robe patterned with double-headed eagles in the portrait of the couple on the chrysobull [document of state] of the Dionysiou Monastery at Mt Athos Greece (Figure 4). Alexios III wore official robes with no eagles (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

From the mid-14th century double-headed eagles appear on the coins of the Trebizond empire and they appear on Catalan maps. The double-, rather than the single-headed eagle seems to have been used as a mark of the empire. (It was, of course, a much more common symbol of the Palaiologan Byzantine empire of Constantinople.) (Bryer and Winfield 1985.)

Figure 4: Alexios III and Theodora Kantakouzene, portrait from a 1385 chrysobull, Dionysiou Monastery, Mt Athos.

Manuel III Komnenos (reign 1390–1417)

The Spaniard, Ruy González de Clavijo visited Trabzon in 1404. He had an audience with emperor Manuel III and his son, the future Alexios IV and reported:

With the emperor was his son, who was about twenty-five years old; and the emperor was tall and handsome. The emperor and his son were dressed in imperial robes. They wore, on their heads, tall hats surmounted by golden cords, on the top of which were cranes’ feathers; and the hats were bound with the skins of martens. (Clavijo 1859, p. 61.)

There was no mention of any emblems on their robes. I speculate there were no eagle symbols on their imperial robes, otherwise the observant Clavijo would have mentioned them.

Eagle Emblem Used by Pontic Greek Associations Today

Pontic Greek community associations in Greece and abroad, especially from the 1970s enriched their iconography with many elements which included, the single-headed spread-winged eagle with its head turned, which appeared on the silver coins minted at Sinope around the 4th century BC (Figure 1). This symbol is most prominent in the press and in Pontic periodicals, the most important being the journal Archeion Pontou [Pontic Archives] (Bruneau 2013). (Note 5.)

The symbol of an eagle on ancient Greek coins from Sinope is the oldest example of this symbol in Pontos. (Sinope on the Black Sea was colonised in the 7th century BC, on an existing settlement, by Greeks from Miletos on the west coast of Anatolia. Sinope then established a Greek colony at Trabzon amongst native Anatolians.)

Conclusion

Symbols of the single- and double-headed eagle had their roots in Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium BC. From there the symbols spread to the Hittites in Anatolia where they were used from 2nd millennium BC. The eagle symbol was used by many people including the Ancient Greeks and Romans. The single-headed eagle first appeared in Pontos ca. 4th century BC on Greek coins from Sinope (Figures 1 and 2). The Byzantines, the Seljuk Turks and Turkmen embraced both symbols. These symbols were also used by the Byzantine Komnenoi emperors of Trebizond (1204–1461). Other people took the symbols from the Byzantines and Turkmen. Today, the single- and double-headed eagle is used by some countries as their emblem and embossed on their flags.

It is a myth that the single-headed spread-winged eagle was the special emblem of the Komnenoi emperors of Trebizond. These emperors used both single- and double-headed spread-winged eagles as symbols.

Since the black double-headed spread-winged eagle on a gold background is now the symbol of the Greek Orthodox Church it is fitting that a unifying symbol for Pontic Greeks should be a single-headed spread-winged eagle based on the ca. 4th century BC coins from Sinope.

Notes

Note 1

Mesopotamia refers to the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, but the region can broadly include what is now eastern Syria, southeastern Turkey, and most of Iraq (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2012).

Note 2

Hayes (2014) states Aristotle believed that the eagle flies high so it can see over the greatest area, thus it was called divine among birds. To the ancients the eagle was seen as divine, owing to it flying close to the heavens and in the manner in which Aristotle described it looking over the earth. The bird became associated with the king sky god Zeus, as well as the sky itself (Wittkower, 1939).

Note 3

In 1897, Russian artist Grigorii Gagarin published a lithograph of the image of Manuel I based on Finlay’s written description (Eastmond 2004). This image by Gagarin is deliberately not produced here, as it was a slight embellishment of the original description and not a drawing of the original portrait.

Note 4

The Palaiologan historian Pachymeres wrote in ca. 1310 that John II agreed to exchange his red shoes for black and to accept the lesser title of Despot of Trebizond, in return for a marriage alliance with Michael’s daughter, Eudokia (Eastmond 2004).

Note 5

The Epitropi Pontiakon Meleton [Pontic Studies Committee] is a scientific, non-profit association founded in 1927 in Athens. It still produces the well-respected academic journal Archeion Pontou [Pontic Archives] which has the distinctive emblem of the spread-winged single-headed eagle with its head turned. It is taken from the Greek Sinope coins [ca. 4th century BC] <www.epm.gr>.

Acknowledgements

I thank Mr Russell McCaskie, Mr Michael Bennett and especially Dr Ruth Macrides for their comments to my work. All errors remain with me.

References

Alexander, RL 1989, ‘A great queen on the sphinx piers at Alaca Hüyük’, Anatolian Studies, vol. 39, pp. 151–58.

Ambrose, K 2013, The marvellous and the monstrous in the sculpture of twelfth-century Europe, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK.

Androudis, P 2015, ‘Double-headed eagles on early (11th–12th C.) medieval textiles: aspects of their iconography and symbolism’, Proceedings of the International Congress: Nis and Byzantium XIV, (ed. M RaKocija), pp. 315–41.

Angelov D & Herrin, J 2012, ‘The Christian imperial tradition — Greek and Latin’, in PF Bang & D Kolodziejczyk (eds) 2012, Universal empire: a comparative approach to imperial culture and representation in Eurasian history, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 149–74.

Bruneau, M 2013, ‘The Pontic Greeks, from Pontus to the Caucasus, Greece and the diaspora’, Journal of Alpine Research, [Revue de Géographie Alpine], 101–2.

Bryer, A & Winfield D 1985, The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, vol. I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Chariton, JD 2008, The function of the double-headed eagle at Yazilikaya, submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts, University of Wisconsin, 19 pp.

Clavijo, RG 1859, Narrative of the embassy of Ruy González de Clavijo to the court of Timour, at Samarcand A.D. 1403–6, (Translated in 1859 from Spanish to English, from the 1582 text by CR Markham.) Reprinted 2005, Hakluyt Society, London.

Deedes, CN 1935, ‘The double-headed god’, Folklore, vol. 46 (3), pp. 194–243.

Eastmond, A 2004, Art and identity in the thirteenth-century Byzantium: Hagia Sophia and the empire of Trebizond, Birmingham Byzantium and Ottoman Monographs vol. 10, Ashgate, Aldershot, England.

Finlay, G 1851, The history of Greece from its conquest by the Crusaders to its conquest by the Turks, and of the empire of Trebizond 1204–1461, William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Hayes, JS 2014, ‘Jupiter’s legacy: the symbol of the eagle and thunderbolt in antiquity and their appropriation by revolutionary America and Nazi Germany’, Senior Capstone Projects, 261.

Himmetoğlu, F 2017, ‘A brief evaluation on the double headed eagle symbol in the old age (Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Central Asia)’ (in Turkish), (abstract), Turan-Sam, vol. 9 (33), p. 199.

Keppie, LJF 1998, The making of the Roman army: from republic to empire, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, USA.

Miller, W 1926, Trebizond: the last Greek empire, (Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London.) Reprinted 1968, Adolf M Hakkert, Amsterdam.

Mylonas, GE 1946, ‘The eagle of Zeus’, The Classical Journal, vol. 41 (5), pp. 203–7.

Peker, AU 1999, ‘The origins of the Seljukid double-headed eagle as a cosmological symbol’, 10th International Congress of Turkish Art Proceedings, (eds F Déroche, C Genequand, G Renda & M Rogers), Geneva, 17–23 September 1995, pp. 559–63.

Wittkower, R 1939, ‘Eagle and serpent: a study in the migration of symbols’, Journal of the Warburg Institute, vol. 2 (4), pp. 293–325.

Sam Topalidis has a Bachelor of Science (Honours) degree and a Masters of Science degree and has extensively researched the history and culture of Pontos, Asia Minor and the Caucasus since 2000. He has published over 12 well-researched and well-referenced articles on Pontos, all of which are located here on the PontosWorld website, as well as other Pontic websites and Blogs. He is also the author of his own family story, A Pontic Greek History which includes a summary of the history of Pontos.