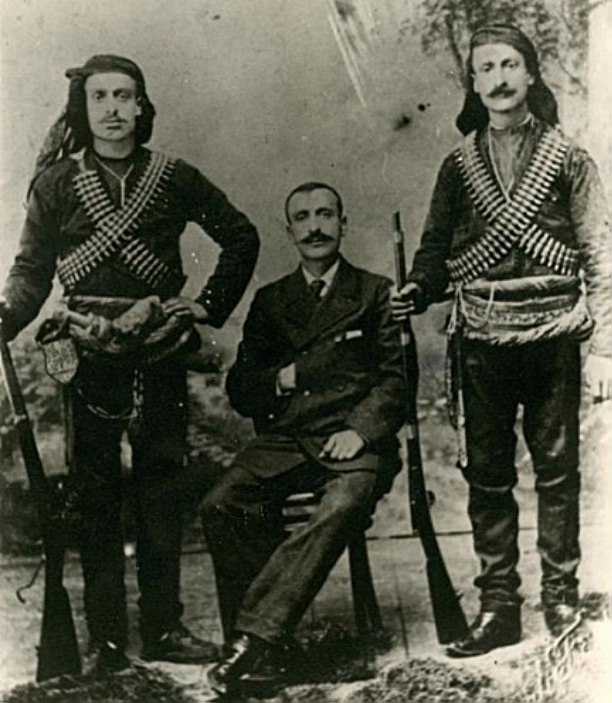

Men from Ishananton, some holding Martini rifles.

Santa, Pontos After 19141

Sam Topalidis (2024)

Pontic Historian

Introduction

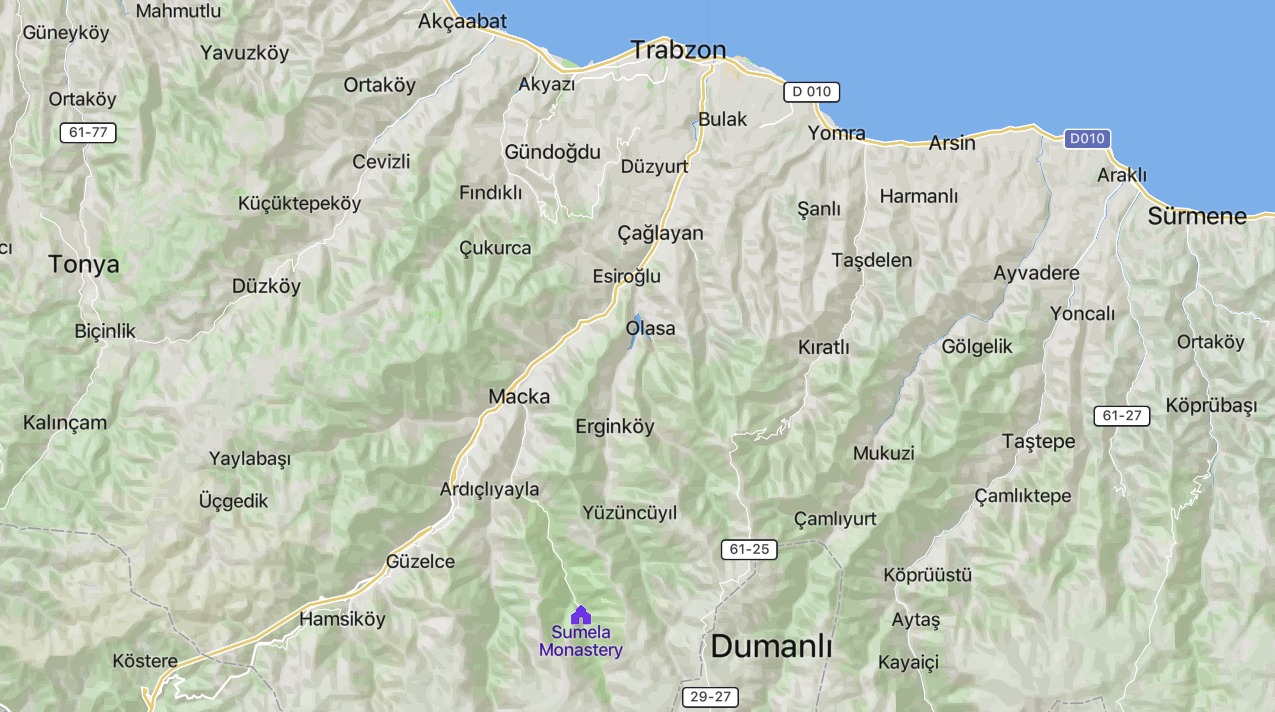

Santa (Turkish Dumanli) is south of Trabzon in north-east Turkiye (Fig. 1). Its seven main districts are, Ishananton (Turkish Işhanli), Kozlaranton (Cinganli), Pinatanton (Binatli), Pistofanton (Piştoflu, also the largest district), Terzanton (Terzili) and Tsakalanton (Çakali) and Zournatsanton (Zurnaçili) (Fig. 2). The Santali were famed for their independence and fighting spirit (Bryer 1968:109).

Fig. 1: Location of Santa (Dumanli) (in Turkish, scale: Trabzon to Sumela monastery = 36 km, https://mapcarta.com/13841388/Map).

History From 1914 to 1923

In April 1915, the leader of a band of Ottoman soldiers appeared in Santa demanding the surrender of any deserters from the Ottoman army. After managing to burn and plunder some of the Greek houses his soldiers were able to assemble 50 men from Santa. They were forced to join labour battalions, nearly all of them died (Nymphopoulos (1953) in Fotiadis (2019:199)).

Fig. 2: The seven main districts of Santa (in Turkish, Google Earth, modified by Abay (2023:63)).

From 1915, Santa had resisted the local authorities and the fanatical Muslims from surrounding villages. For many years, local Muslims had been laying claim to the rich pastures owned by the Santalis—this often led to conflict. In 1916, in order to maintain their independence, the people of Santa formed a guerrilla group. The Russian occupation of north-east Anatolia in 1916–February 1918 (during World War I) restored the life of Santa. The retreat of the Russian army in February 1918 resulted in a return to insecurity (Abay (2023:65); Fotiadis (2019:421–422)).

In the occupied Ottoman territory, chaos ensued. The Turks concluded a formal armistice in December [after Lenin’s Bolshevik’s October 1917 revolution]. By the end of December 1917, Russian soldiers in Trabzon began leaving Anatolia. Disorder in the town was magnified in the surrounding countryside, as Turkish armed bandits gained control. By the end of January 1918, the American consul in Trabzon reported the ‘Turkish bands are getting more audacious and the Russian soldiers obnoxious’ (Rogan 2015).

In January 1918, Chrysanthos, Greek metropolitan of Trabzon, alerted Ottoman General Vehid Pasha of the damage that the Ottoman armed brigands were doing to the Christians in the Trabzon region. Chrysanthos then distributed firearms to the Greeks for their own protection. Thanks to this measure and to the resistance offered over several days the districts, including Santa, were saved (Greek Patriarchate 1919).

In September 1919, 200 women and 15–20 men returning to Santa from Trabzon were attacked by an Ottoman band. Three Greeks died and two were injured. Five men from the Ottoman band were killed with 11 wounded (Fotiadis 2019:304–305).

Efraimidis remembered how Turkish brigands would raid the [Greek] villages close to Santa. The Santalis had formed a guerrilla group for their own protection led by Euclid Kourtidis (Plates 1–2). Some 80 to 100 young armed men from the surrounding villages joined this group. The group dug trenches around the nearby villages of Ftelen, Haratsanton, and Kopalanton which were close to Turkish villages. Throughout winter these passes were guarded. Turkish brigands repeatedly tried to loot villagers on their way to Trabzon in winter (winter lasted five months in the region) (Efraimidis (1972–1974) in Fotiadis (2019:422)).

The Kemalist government [established in 1920 at Ankara] implemented harsh military measures to supress the Santa guerrillas (Fotiadis 2019:422). In early September 1921, the Turkish military ordered that all males aged between 20 and 45 years from Santa to enlist for military service [to join the labour battalions] otherwise they would attack Santa and all residents would be deported [to a distant region]. Then on 6 September, the Ottoman army occupied Ishananton, Pinatanton and Terzanton (Fig. 2). The men were locked up in the St Kyriake Greek church in Ishananton. N Topalidis2 who was one of these men captured in this church wrote that he saw from the church window women and children from Zournatsanton being ousted from their homes and beaten. The men were moved from the church to Pistofanton where they had also gathered women and children from the surrounding districts (N Topalidis (1952) in Fotiadis (2019:423–424)).

On 10 September, many people from six Santa districts were captured and deported. Two days later, the villagers of Pistofanton were also deported (Fotiadis 2019:424). The convoy stopped at Hunuz [Χουνούς, Fig. 3]. The second stop was Erzurum [Ερζερούμ] where the convoy was struck with typhus. Later, 200 people were sent from Erzurum to Erzincan [Ερζιγκιάν]. When the Lausanne Convention was signed in January 1923 (with the implementation of the population exchange, Note 1), the deported Santalis moved to Greece (Athanasiadis (1967) in Fotiadis (2019:425)). Chimonidis, who was one of the men exiled from Santa, stated that of the 370 souls that reached Hunuz in October 1921, less than 200 returned in January 1923 (Fotiadis 2019:430).

The only people left in the Santa area were the guerrillas and 300 women and children who had followed them to the mountains following the occupation of the Santa villages by the Kemalist army. They were followed by others, leading to over 400 non-combatants. Food was scarce (Fotiadis 2019:425).

The Santa guerrillas fought against regular and irregular Kemalist armies until the 1923 population exchange. Some Santalis fled to the Soviet Union while others reached Trabzon and caught boats to Istanbul or to Greece. Those who were arrested by local authorities were taken to the Independence Courts and sentenced to death (Fotiadis 2019:428, 430).

Plate 1: Pilides brothers from left, George, Theodoros and Isaac from Zournatsanton, 1919 (Source)

Plate 2: Ishananton guerrillas, [some holding Martini rifles] (Source).

Fig. 3: The journey of the exiled Santali [from Σάντα] and their return to Trabzon [Τραπεζούντα] (in Greek, scale: 180 km, Τραπεζούντα to Ερζερούμ, Source.

Recent Actions to Protect Historic Santa

After the 1923 population exchange, these Santa settlements were abandoned and became the property of the Ministry of Treasury and Finance. The seven main districts remained deserted until 1930, when they started to be used as summer highland pastures by people from the surrounding districts who had purchased the majority of the houses and the building lots in Santa. These seven districts of Santa remain underpopulated. There are no accommodation facilities for tourists in the districts, however, there is a guesthouse under construction (as at 2022) in Zournatsanton (Abay 2023:1–2, 66, 76).

The first Turkish action for the conservation of Santa dates from 1978 when the districts of Santa were designated as sites to be protected. Current tourism is limited. Plans aim to achieve a balance between conservation and use and to increase tourism. Within its framework, the ‘Eastern Black Sea Tourism Master Plan’ began to be prepared for the Eastern Black Sea Region in 2007. The ‘Green Road Project’, which is still in progress, was developed within the scope of the tourism master plan (Abay 2023:148, 150–151).

Today, three districts; Pistofanton, Ishananton and Zournatsanton, are used more frequently in summer. Access to Santa, as well as between districts, is still challenging as the roads are closed for long periods of the year. The site remains uninhabited for most of the year with Tsakalanton and Kozlaranton in particular now almost uninhabited (Abay 2023:155, 167–168).

The historic buildings are rapidly deteriorating. Houses are changed by the owners or replaced with modern buildings that are inappropriate in the historical context. In addition, churches, schools, fountains and paved roads are being destroyed by treasure hunters and vandals (www.haberlobi.com/foto-galeri/tarihi-ve-turistik-hazine-santa-harabeleri-restorasyon-calismalarini-bekliyor (19 July 2022)).

It is difficult for the Pontic Greek tourists to perform commemorative ceremonies at Santa as most of the buildings are privately owned (Abay 2023:183).

The Future

Research into title deeds is needed to obtain information on the ownership of the buildings in the districts. Surveys with the property owners of Santa, as well as the descendants of Pontic Greeks of the area will enable a better understanding of the ‘contested’ values of these groups. Once this information is obtained, effective heritage strategies need to be developed (Abay 2023:186).

Note 1

Population exchange

The Greek army was defeated in late August 1922, in western Anatolia during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). This exposed the Christian population in Anatolia to retaliation by irregulars and the Turkish army (Hirschon 2003b). The Turks then started to force Greeks out of Anatolia.

The Lausanne Convention signed in January 1923 concerned the terms for the compulsory exchange of Christian and Muslim populations between Greece and Turkey. The exclusion of the Orthodox inhabitants of the Aegean Islands of Imbros and Tenedos, however, was specified in the later Lausanne Treaty (signed in July 1923) (Hirschon 2003a).

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the comments received by Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie to an earlier draft.

References

1. This article follows on from the author’s article ‘The former Greek Orthodox churches in Santa, Pontos’ at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/858-early-history-and-churches-of-santa

2. The author can’t verify if he was a relative.

Sources

Abay P (2023) An assessment and re-identification of the rural heritage site of Santa (Dumanliköy, Gümüşhane), MSc thesis, January 2023, Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

Bryer A (1968) ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes Part 2’, Archeion Pontou (Archive of Pontos) 29:89–129.

Fotiadis KE (2019) The genocide of the Pontian Greeks, (unknown translator from Greek into English), KE Fotiadis, (unknown place of publication).

Greek Patriarchate (1919) Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey 1914–1918, (Greek Patriarchate in Constantinople), Hesperia Press, London.

Hirschon R (2003a) ‘Notes on terminology and orthography’, in Hirschon R (ed) (2003c):xi–xiii.

Hirschon R (2003b) ‘‘Unmixing peoples’ in the Aegean region’, in Hirschon R (ed) (2003c):3–12.

Hirschon R (ed) (2003c) Crossing the Aegean: an appraisal of the 1923 compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey, Berghahn Books, New York.