Sam Topalidis (August 2016)

Introduction

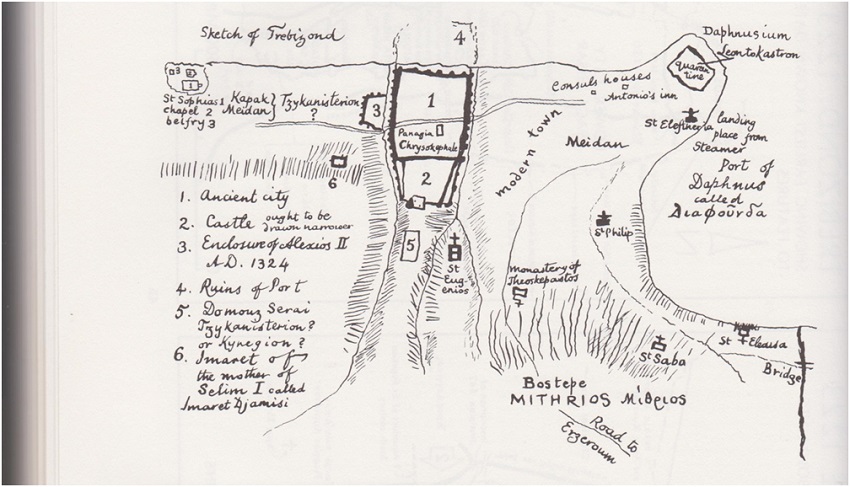

The convent Panayia Theoskepastos monastery stands on the northwestern slopes of the 240 m high Boztepe (Grey Hill), midway between the harbour of Daphnous and the citadel overlooking Trabzon’s eastern suburbs (Figure 1). Its high walls enclose steep, rocky ground with the entrance, cells and domestic buildings at the bottom (north) of the compound and the cemetery at the top. Like many Trapezuntine monasteries it is built round a cave chapel, with a holy spring. Apart from the nearby christian Armenian monastery at Kaymakli, it was the only medieval religious house in Trabzon to have survived until 1922 when they were abandoned during the Exchange of Populations (Bryer 1968).

In order to increase tourism to the Black Sea port of Trabzon in the northeast corner of Turkey, Trabzon’s mayor is fostering restorative projects like the Greek Orthodox monastery Panayia Theoskepastos (God-protected, called Kizlar Manastiri in Turkish) (Figure 1) by the Culture and Tourism Ministry. The ‘renovated’ monastery will open soon, but no date has been given (Turkish Newspaper Daily Sabah published 17 June 2016).

Figure 1 Sketch of Trabzon in 1850 by Finlay (Bryer and Winfield (1985) between pp. 194 & 195)

History

The cave in the hillside of the monastery was probably once associated with the cult of Mithras [Persian god of the sun – see Note A]. Afterwards the cave may have been a church before it was incorporated into the Theoskepastos monastery, which was probably founded, refounded, or endowed in the 1340s by Eirene (mother of Grand Komnenos Alexios III of the Trebizond empire). The monastery held extensive properties and was the only known convent in the pocket Byzantine empire of Trebizond. The monastery housed the tombs of Andronikos (d. 1376) son of Alexios III, of Grand Komnenos Manuel III (d. 1417) and of Grand Komnenos Alexios IV (d. 1429) before the latter’s remains were transferred to outside the Panayia Chrysokephalos church (Figure 1) (Bryer and Winfield 1985). [The remains of Alexios IV now lie at the Panayia Soumela monastery near Veria in northern Greece.]

During the local wars in 1758–9 between the Derebeys (valley lords) and the Pasha of Trabzon, the central and lower walled cities, the St Eugenios church and the walled Theoskepastos monastery were used as Derebey strongholds against the Pasha and his Janissary garrison in the upper citadel (Bryer 1969).

By 1609 the cave church was served by up to five monks who lived outside the monastery’s enclosed wall. By the time of the ‘restorations’ of 1843 this became a parish church out of the nun’s hands (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

Until 1843 the monastery consisted of the painted cave church, some individual cells and the ruined hall. This changed after 1843 when the church was enclosed by a wall in front and an antechamber forming one side of the court of the monastery. Then the abbess ruined the well preserved portraits of Grand Komnenos Alexios III (1349–90), his wife Theodora Kantakouzene and his mother Eirene when she had the walls of the church on the outside within the vestibule newly plastered and painted. These original portraits were unfortunately replaced with figures of Theodora, Alexios III and Andronikos (Bryer 1968; Bryer and Winfield 1985).

Building continued in the Theoskepastos throughout the second half of the 19th century. A large range was added (probably after 1889) on the north side of the courtyard. A belfry was erected beside the hall (Figure 2). To the northeast of the cave church a small chapel was built. The western end of the chapel abuts the side of the cave church. The chapel’s drum and dome have been destroyed. The St Constantine church was also built in the southeast corner of the compound by Trabzon’s Greek Metropolitan Constantios (reign 1830–79) (Bryer 1968).

In 1916, the Russian officer, Sergei Mintslov, observed that in the cave church an icon-portrait of Alexios Komnenos and his wife could still be seen. He also noted that the nun’s cells seem to hang over the cliff (Mintslov 1923).

Bryer and Winfield mentions the wall paintings of the cave church were preserved under a heavy layer of grime (Bryer and Winfield 1985). By the late 1980s, these frescoes were badly damaged (Yücel 1988).

Figure 2: Courtyard of the convent from the southeast (1967). Entrance to the cave church is bottom left. Entrance to the convent is under the belfry (Bryer 1968, p. 100)

Architecture

Bryer and Winfield (1985) state the Theoskepastos comprised the following features:

- A walled rectangular enclosure on the hillside around half an acre in size.

- A series of cells for up to 12 nuns, replaced in 1843 by the present range of small cottagelike cells to the northeast and after 1889 by the two-storied building to the northwest.

- A small 19th century Byzantine chapel adjoining to the east of the cave church.

- A large fountain seen in 1609 and now lost around the northwest and only entrance.

- The 19th century church of St Constantine above the cave church in the southeast corner.

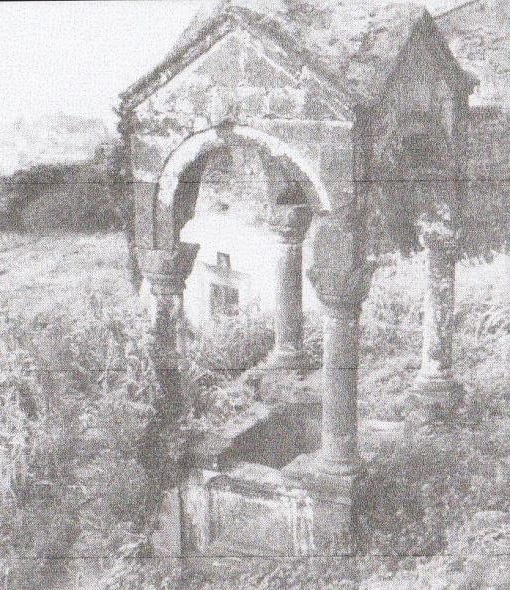

- The tomb of the Greek Metropolitan Constantios of Trabzon (1879) (Figure 3) above the cave church at the highest point of the monastery.

- A large two-storied hall to the west of the cave church (Figure 2); and

- The cave church in the hillside (Figure 2) with remains of a holy spring.

Figure 3: Tomb of Trabzon Metropolitan Constantios (1967) (Bryer 1968, p. 103)

Recent Renovation

In 1970 the monastery was controlled by the local children’s hospital (Bryer and Winfield 1985). In 1978, the Turkish Ministry of Tourism realised the site’s tourism potential and locked the building for future renovation. The main compound was in a sad state of vandalism (Trabzon Travel Guide at: www.karalahana.com). In 2003 I witnessed the sad state of decay of its exterior.

In 2006, excavations had commenced at the monastery. In 2007, Trabzon’s mayor had prepared a project to turn the monastery into a contemporary art centre (Turkish Newspaper Hürriyet Daily News published 24 September 2007). Restoration of the monastery began in 2014 which included the historical cave church and the rare frescoes. The cost of the restoration project is nearly $1.6 million Turkish Lira (Turkish Newspaper Hürriyet Daily News published 30 January 2015).

No date has been set for the opening of the ‘renovated’ monastery. It is hoped the restoration of the frescoes will be made appropriately. I look forward to visiting the site.

Note A

St Eugenios and his martyrs were believed to have been put to death under Roman Emperor Diocletian (284–304 AD) when they overthrew the statue of Mithras on Mt Minthrion (Boztepe) (Bryer and Winfield 1985).

The existence of Mithras descriptions on nine of Trabzon’s minted coins in the Roman period in the late 2nd century to the mid-3rd century AD depict that there was a type of worship related to Mithras in the town (Keleş 2008).

In the Roman Empire during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, Mithras was honoured as the patron of loyalty to the emperor. After the acceptance of Christianity in the early 4th century, Mithraism rapidly declined (Encyclopaedia Britannica 2012).

Acknowledgements

I warmly acknowledge the work on the Theoskepastos monastery by Emeritus Professor Anthony Bryer OBE which I have summarised here. I also thank Mr Russell McCaskie for translating into English the Russian text Mintslov (1923) and Mr Michael Bennett for his comments on an earlier draft.

References

Bryer, A 1968, ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes Part 2’, Archeion Pontou [Pontic Archives] vol. 29, pp 89–129.

Bryer, A 1969, ‘The last Laz risings and the downfall of the Pontic Derebeys, 1812–1840’, Bedi Kartlisa, Revue de Kartvelologie, XXVI, Paris, pp. 191–210.

Bryer, A & Winfield, D 1985, The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, vol. I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington D.C., USA.

Keleş, V 2008, ‘Cult of Mithras and the Mithras descriptions on Trapezous city coins’, Cercetări Numismatice, XIV, pp. 220–31.

Mintslov, SR 1923, Trapezondskaia epopeia, [Russian accounts of Trabzon], Sibirskoe Knigoizdatel’stvo, Berlin, Germany. [English translation provided by Russell McCaskie.]

Yücel, E 1988, Trabzon and Sumela, [Translated into English from Turkish by N Erbey], Net Turistik Yayinlar A.Ş., Istanbul, Turkey.

Current view. Source