Fig. 1: Pontos, north-east Türkiye (Bryer and Winfield 1985:iii)

By Sam Topalidis1

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist (2024)

What is Romeyka and How Did it Develop?

From the 7th century BC, Greeks established colonies in Pontos, in north-east Anatolia near the Black Sea (Fig. 1). In the 11th century, when the Seljuk Turks invaded Anatolia, the Greeks in Pontos and the Greek spoken there became isolated from other Greek speaking areas (Mackridge 1987). Then in 1461, with the fall of the Komnenoi Byzantine empire of Trebizond to the Ottoman Turks, many Christians in the areas around Trabzon were slowly converted to Islam.

Romeyka was the Greek dialect spoken by most Greeks in Pontos. However, in the early 1920s, when the Christian Greeks were forced out of Turkish territories to Greece under the compulsory Exchange of Populations2, the Romeyka dialect began including words from modern Greek and is called Pontic Greek (Note 1).3

This isolation of Pontos would help to explain the preservation of many medieval characteristics in Romeyka in Türkiye and its Muslim diaspora and Pontic Greek spoken in Greece and its diaspora today that have disappeared elsewhere. There are hundreds of words in Romeyka (and Pontic Greek) that are unfamiliar to other Greek dialects. There is also a number of archaic words and forms that are preserved in the dialect (Mackridge 1987). So it is not surprising that to modern Greek speakers, Pontic Greek and Romeyka are generally incomprehensible.

Professor Ioanna Sitaridou (Cambridge University, Plate 1), who is of Pontic Greek descent, has analysed Romeyka in Türkiye. All other known Greek dialects have stopped using the infinitive found in ancient Greek. So speakers of modern Greek would say, for example, I want that I go instead of I want to go. However, in Romeyka, the infinitive lives on and this ancient Greek infinitive can be dated back to Hellenistic Greek. Its preservation in a structure which became obsolete by early Medieval times continued to be used in Romeyka (Note 2) (www.cam.ac.uk published 3 April 2024).

Plate 1: Professor Sitaridou (right) with Romeyka speakers in Türkiye’s Trabzon area (Source)

Where in Pontos is Romeyka Spoken Today?

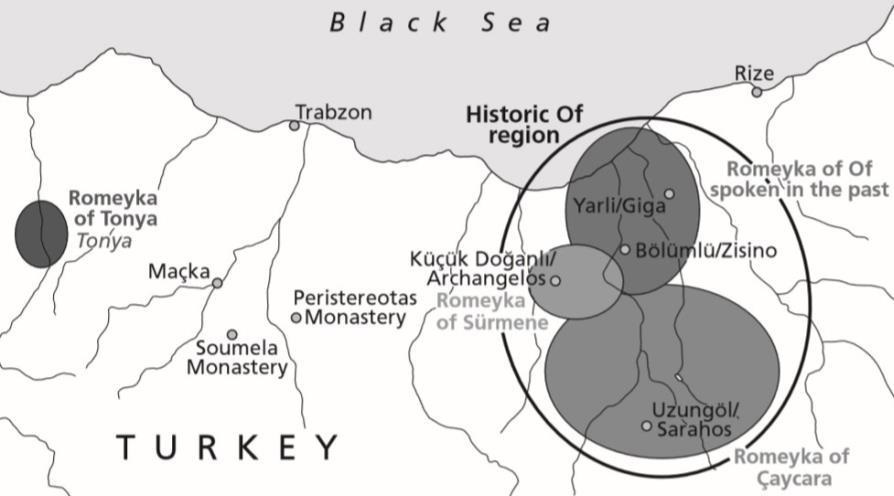

With the Exchange of Populations, Romeyka-speaking Muslims stayed in Anatolia which explains why this Greek dialect survives in small enclaves in the Trabzon area (www.romeyka.org/rediscovering-romeyka/). Normally, a linguistic shift to Turkish accompanied the Islamisation of communities across Anatolia, but these communities in the Trabzon area (by maybe a couple of thousand people) have instead retained Romeyka to this day. Today, Romeyka is spoken in a number of valley systems across the Trabzon area including Çaykara (south of Of), Tonya (south-west of Trabzon) and Sürmene4 (east of Trabzon) (and Maçka5), (Fig. 2) as well as in major Turkish cities (such as Istanbul) and the diaspora such as Berlin, due to Turkish migration. Romeyka was not a written language (it was not taught in schools) and with its dependence on oral transmission across generations, Romeyka continues to permeate local culture especially in secluded rural communities across the valleys of Trabzon. Communities refrain, at least openly, from identifying with the language out of fear that their heritage might be perceived as antagonistic to their Turkish-Muslim identity. Sitaridou, argues that Romeyka constitutes a separate branch of Greek within the Greek language family—not a ‘daughter’ of medieval/modern Greek, but rather a ‘sister’ (Sitaridou and Sağlam 2020).

Sitaridou also conducted field work in Tonya (south-west of Trabzon, Fig. 2) and revealed significant grammatical variation in Romeyka between the valleys. It is argued that both the syntax of subordination and negation systems in the Tonya version show different patterns and thus diachronic development from the Çaykara [Of] variety (www.cam.ac.uk published 3 April 2024). A less well studied aspect of Romeyka was its vocabulary. Vahit Tursun has written a dictionary of Romeyka spoken around Trabzon (including Tonya) (Mackridge, http://kars1918.wordpress.com).

The most archaic form of Romeyka has survived among the Muslims from the Of region (Fig. 2), who had predominantly Christian Greek ancestors and who, under pressure from the valley lords in the 17th century converted to Islam. [Many Greeks became crypto-Christians, i.e. they openly converted to Islam, but retained their Christian beliefs and practices in secret.]6 In the past, many Turkish settlers near Of became Romeyka speakers since it was the major local language (Mackridge 1987).

Fig. 2: Romeyka speaking areas, north-east Türkiye (Trabzon to Rize = 67 km, (Source)

What is the Future For Romeyka?

Romeyka is classified as ‘definitely endangered’ by UNESCO. Its integrity is under serious threat through further contact with Turkish in the broader community. Romeyka is not taught in schools and is the last surviving variety of Greek spoken in eastern Türkiye today (www.romeyka.org/rediscovering-romeyka/). Indeed, Romeyka is thought to have only a couple of thousand native speakers left in the Trabzon area and fewer young people are learning the dialect.

Urgent action is needed if this Greek dialect is to be preserved (Sitaridou and Sağlam 2020). The crowd sourcing initiative, led by Professor Sitaridou, aims to preserve the sound of Romeyka by inviting people to upload audio recordings of Romeyka being spoken in order to build a repository (crowdsource.romeyka.org/).

In Greece, Sitaridou has co-introduced a pioneering new course on the Pontic Greek dialect at the Democritus University of Thrace since the number of speakers of Pontic Greek in Greece [and the Greek diaspora7] is also dwindling (www.cam.ac.uk published 3 April 2024).

Are you a Romeyka or Pontic Greek speaker? We can help to keep Romeyka and the Pontic Greek dialect alive by learning Pontic songs which are sung at Pontic functions (Romeyka: Watch video and Pontic Greek: Watch video).

Notes

Note 1

Professor Sitaridou from Cambridge University prefers to use the term Romeika, which is what the majority of speakers refer to their language. In the Seljuk Turk and then the Ottoman Turk periods, the term Rum was used for lands that were under the Roman/Byzantine (Eastern Roman) empire and subsequently came under Turkish rule. However, the term Romeika commonly referred to vernacular modern Greek up to the 20th century; furthermore, the term does not adequately distinguish between Romeika in Pontos today and Greek varieties today spoken in other areas around the Black Sea (e.g. in Georgia), which are also known as Romeika. For these reasons researchers in the field spell Romeyka as the Greek varieties of Pontos as spoken today by Muslims (Sağlam (2017:92); www.romeyka.org/rediscovering-romeyka/).

Note 2

Initial descriptions of the infinitive’s survival in Romeyka are found in Parcharidis (1880), Deffner (1878) and Dawkins (1937), whereas the next publication in which Romeyka receives significant attention is Mackridge (1987) (www.romeyka.org/rediscovering-romeyka/).

Sürmene used to have a plain infinitive, which was, however, reanalysed as an inflected infinitive at least 100 years ago. However, in geographically adjacent varieties of Sürmene, as in Çaykara (Romeyka of Of), we do indeed see the preservation of a plain infinitive as well as a personal one; but, crucially, there is no inflected infinitive in Çaykara, although there is a personal one (Sitaridou (2021:166).

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for the assistance given to me by the late Peter Mackridge, Emeritus Professor of Modern Greek University of Oxford, on Romeyka, the Pontic Greek dialect and the development of the Greek language. I also wish to thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

1. The author is from Canberra, Australia (

2. The Exchange of Orthodox and Muslim Populations between Greece and Turkey was under the Lausanne Convention (signed in January 1923). Most of the Greeks in Istanbul were exempt from this exchange. The exemption of the Orthodox inhabitants on the islands of Imbros and Tenedos [in the north-eastern Aegean Sea] was specified in the wider Treaty of Lausanne signed in July 1923 (Hirschon 2003:8). Protestant Pontic Greeks also moved to Greece, see: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/823-american-protestant-missions-in-pontos

3. Similarly, when Pontic Greeks moved to Georgia, their Romeyka dialect absorbed new words from Russian and Georgian and their Greek dialect is called Romeika (Berikashvili 2017:17).

4. Most of the male Romeyka speakers in the Trabzon area also spoke Turkish (Mackridge (1987:117).

5. After a flood in 1929, homeless people from Beşköy (south of Of) were assigned houses in a district 10 km west of Maçka. Interestingly these houses originally belonged to Pontic Greeks who left during the Exchange of Populations (Özkan 2013:2).

6. Words within square brackets ‘[ ]’ within a reference are the author’s words.

7. Some Pontic Greek communities in Greece and the diaspora have organised courses to teach the Pontic Greek dialect.

Sources

Berikashvili S (2017) Morphological aspects of Pontic Greek spoken in Georgia, Lincom GmbH, Munich.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Dawkins RM (1937) ‘The Pontic dialect of modern Greek in Asia Minor and Russia’, Transactions of the Philological Society:15–52.

Deffner M (1878) Die Infinitive in den pontischen Dialekten und die zusammengesetzten Zeiten im Neugriechischen, Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussicshen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Aus dem Jahre 1877. Berlin: Buchdruckerei der KGL. Academie der Wissenschaften. [in German, The infinitives in the Pontic dialects and the compound tenses in modern Greek, Monthly reports of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. From 1877: KGL Printing Press, Academy of Sciences, Berlin.]:191–230.

Hirschon R (2003), ‘’Unmixing peoples’ in the Aegean region’, in Hirschon R (ed) (2003) Crossing the Aegean: an appraisal of the 1923 compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey, Berghahn Books, New York.

Mackridge P (1987) ‘Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey: prolegomena to a study of the Ophitic sub-dialect of Pontic’, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 11:115–137.

Özkan H (2013) ‘The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims in the villages of Beşköy in the province of present-day Trabzon’, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 37(1):1–21.

Parcharidis I (1880) Γρακκαηηθή ηες δηαιέθηοσ Τραπεδοσληος: Περί επηζέηωλ, αληωλσκηώλ θαη βαρσηόλωλ ρεκάηωλ, Χεηρόγραθο 335, Κέληρο Ερεύλες ηωλ Νεοειιεληθώλ Δηαιέθηωλ θαη Ιδηωκάηωλ, Αθαδεκία Αζελώλ [in Greek]

Sağlam E (2017) Constitutive ambiguities: subjectivities and memory in the case of Romeika-speaking communities of Trabzon, Turkey, PhD thesis, University of London, London.

Sitaridou I (2021) ‘(In)vulnerable inflected infinitives as complements to modals: evidence from Galician and Romeyka’, in Jónsson JG and Eythórsson T (eds) (2021) Syntactic Features and the Limits of Syntactic Change,:161–177, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Sitaridou I and Sağlam E (2020) ‘Romeyka heritage in contemporary Turkey: socio-linguistic explorations of endangerment and preservation’, Heritage Turkey, British Institute at Ankara, 10:20–21.