Plate 1: The ruined St George Greek metropolitan Church, Gümüşhane 2022 (Source)

Sam Topalidis (2025)

Pontic Historian and Ethnologist

Introduction

The Benaki Museum in Athens is one of the institutions in Greece which received precious ecclesiastic artefacts that the Anatolian Greek refugees saved after the Exchange of Populations in the early 1920s (Note 1). These church items, many made with silver, are examples of artistic creativity between the 16th and 19th centuries (Delivorrias 2011:10).

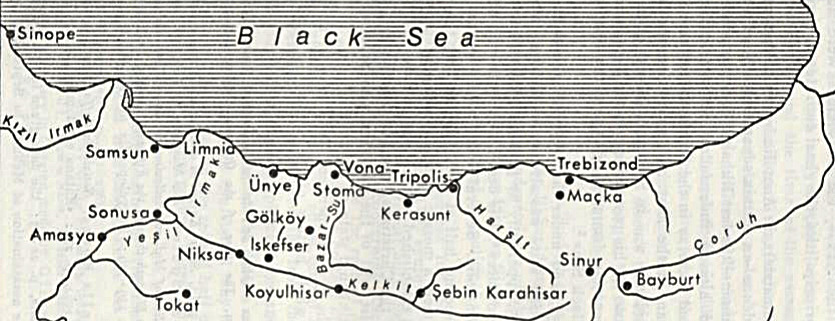

This study focuses on some of the silver artefacts that Pontic Greek refugees (Fig. 1) salvaged from the St George Greek Orthodox Church in Gümüşhane, Pontos (Plate 1) which are now in the Benaki Museum.

Fig. 1: North-east Anatolia (Pontos) (Amasya to Trebizond = 330 km, Zachariadou 1979:335)

Gümüşhane

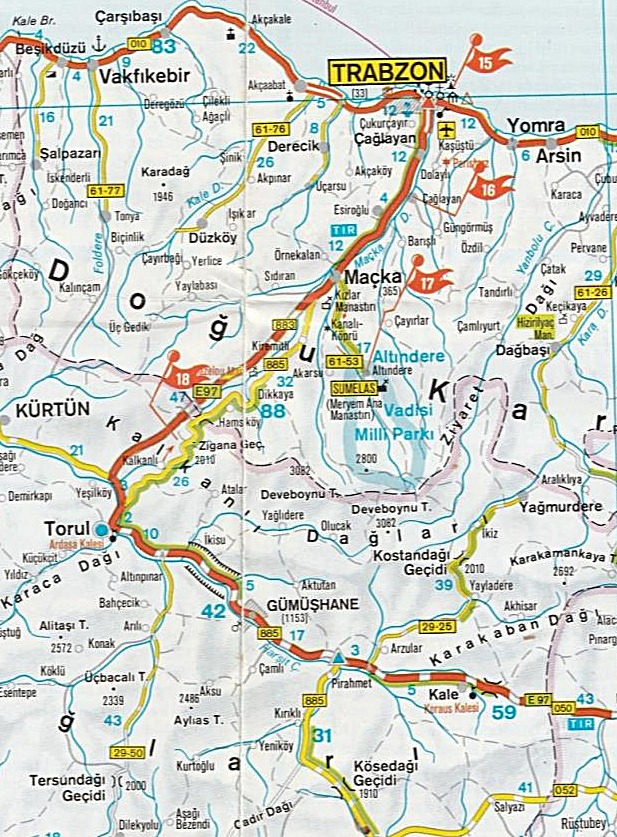

From 1204 to 1461, Chaldia [a region over the Pontic Mountains south of Trabzon, from Torul around Gümüşhane and Kromni (35 km by road north-east of Gümüşhane) and Fig. 2] became part of the small Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Komnenoi empire of Trebizond. From 1479, it was incorporated into the Ottoman empire (Bryer 2009:520).

The rapid growth in the late 16th century Christian population in Chaldia was due to the increased growth in mining activities. The powerful local superintendents of silver mines among the Greek population seem to have contributed greatly to the Christian ecclesiastical autonomy of the area (www.ehw.gr/asiaminor/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=10204). The important silver mining town of Gümüşhane (Turkish for silver city) about 94 km by road south of Trabzon was established in the 1590s. The town lies along the Harşit River at an elevation of 1,500 m (Fig. 2). (Its Greek name of Argyropolis was concocted by 1846.) The silver mines also produced much lead and a little gold (Note 2) (Bryer (1991); Bryer and Winfield (1985)). At its height, the Gümüşhane area was like a state within a state which, as long as it produced precious metal for the Ottoman sultan, functioned with the blessing of both sultan and Orthodox patriarch (Ballian 1995:212).

Plate 1: The ruined St George Greek metropolitan Church, Gümüşhane 2022 (Source)

In 1644, Evliya Çelebi noted that the Ottoman treasury was enriched each year by 7,000 kg of silver from Gümüşhane alone (see Topalidis 2024). From at least the mid-17th century, Greeks from the Gümüşhane area worked in silver mining, smelting or in the related charcoal burning [/tree-felling] industries. For their work, Christian villagers were excused the payment made by non-muslims in lieu of military service. From 1718, parts of the silver-producing areas of Ottoman Serbia were ceded to Austria. As a result, the Chaldian mines became the most important source of metals in the Ottoman empire (Ballian (1995:83); (2002:341)).

Gümüşhane drew its charcoal from an area later to be closely identified with crypto-Christianity (people who had openly converted from Christianity to Islam, but retained their Christian beliefs and practices in secret). When the mines were at their peak, the town of Gümüşhane consisted of 2,250 Greek families [around 11,250 Greeks or 86% of all families], 180 Armenian families and 200 Turk families. The mines were in decline before the Russian army reached Gümüşhane in 1829 (Ballian (2002); Bryer and Winfield (1970)).

In 1857, Gümüşhane had around 7,500 people of which 53% were Muslims, 27% Greeks and 20% crypto-Christians (Bryer 1983). The end of silver mining coincided with the building of the Trabzon to Erzurum highway which bypassed (old) Gümüşhane by 4 km to the location of a new town. By at least 1869, new Gümüşhane became a centre of a soft fruit industry (Bryer and Winfield 1970:330, 333).

Fig. 2: Map of Trabzon to Gümüşhane area (Euro-Holiday map, Turkey: Black Sea, East Coast; Trabzon to Gümüşhane = 64 km)

In February 1918, when the Russian army left north-east Anatolia, thousands of Christians migrated to Russia and the Caucasus. The remaining Greeks (who had survived the deportations after World War I, were forced to leave Anatolia for Greece from September 1922, after the defeat of the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish War. The forced expulsion was finalised from January 1923 under the Exchange of Populations.

Church Silverware

Many of the preserved Pontic Greek ecclesiastical artefacts at the Benaki Museum, Athens mention the donor’s name, but sometime they include the motivation for the donation, the place, the date and the manufacturer’s name. Some of these artefacts, mostly from the St George Greek metropolitan Church in Gümüşhane, are now described.

1726–1727 chalice and lid

In Orthodox Christian usage the chalice is a goblet used to offer Communion during the liturgy. The 50 cm tall chalice with lid was made by George the Goldsmith in 1726 (lid 1727) in silver, parcel gilt (partially gilded), niello [a black metal alloy] and semi-precious stones (Plate 2). It was donated to the Church of St George in Gümüşhane for the salvation of the soul of Stephanos Phytianos and his wife and parents (Ballian 2011:93). In 1723, Ignatios Phytianos founded the St George Greek metropolitan Church in Gümüşhane (Bryer and Winfield 1970). Today, the church is in ruins (Plate 1). The donor, Stephanos Phytianos, was master miner in the Torul district. He contributed to the repair of the Choutoura Monastery near Gümüşhane, to the founding of a church in his village of Phytiana in Torul and the creation of the Greek school in Gümüşhane. According to tradition, a patriarch, eight metropolitans and five abbots came from Phytiana (Bryer et al. 1972–1973:219–227).

Plate 2: Chalice, Gümüşhane, 1726–1727 (author’s photo 2024, Benaki Museum, Athens)

1736 Pectoral of Michael Sarasites

The 7 cm high priestly pectoral was donated by Michael Sarasites in 1736, from Gümüşhane to the Church of St George, Gümüşhane. It is made of silver gilt, filigree enamel, coral with a carved wooden core (Plate 3). The pectoral is in the form of a small book and hangs on a long chain decorated with a crucifix, a rosette medallion and coral beads. For around 200 years the Sarasites family held the post of master miner general and were effectively the political and ecclesiastical authority in Gümüşhane. (Ballian 2011:90).

Plate 3: Pectoral, 1736, St George Church Gümüşhane (author’s photo 2024, Benaki Museum, Athens)

1739 Mitre of the archbishop of Amida

A mitre is a crown used by an archbishop in the Orthodox religion. This mitre is 25 cm high and 20 cm in diameter, made in 1739 of silver, parcel gilt, semi-precious stones and pearls (Plate 4). In 1762, the mitre was purchased by the chief of the refinery of the mines, Lambrianos and dedicated to the Church of St George, Gümüşhane. The mitre was originally given to Agathangelos, archbishop of Amida (Diyarbakır) (Ballian 2011:96).

Plate 4: Mitre, Gümüşhane, 1739 (author’s photo 2024, Benaki Museum, Athens)

Benediction cross with silver gilt mount

This 17th century[?] cross from Gümüşhane is made of silver gilt and enamel, has a carved wooden core and is 37.5 cm high and 19.3 cm wide (Plate 5, note that the museum labels the cross as 18th century). Carved wooden crosses of this type were used for blessing and consecration. The polygonal handle may have been made later (Ballian 2011:104).

1802 Silver dish, Greek Church of the Annunciation

This 1802 silver dish from the Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation in Trabzon was used for the consecrated bread, for the memorial offering of boiled wheat, or the collection of contributions (Plate 6) (Benaki Museum display description). It is expected that the dish was made from Chaldian silver.

The Greek Church of Annunciation is believed to be the Theotokos Evangelistria Church in Trabzon (Talbot Rice 1929–30). The church was demolished sometime between 1929 and 1958.

Plate 5: Benediction cross, Gümüşhane 18th century (author’s photo 2017, Benaki Museum, Athens)

1729 liturgical fans and processional cross, St George Church

Liturgical fans, usually in pairs, are large metal disks that can be mounted on poles. They are used in processions [carried by altar servers] and used inside churches symbolising the invisible presence of angels during the liturgy (www.oramaworld.com/en/c/3000_3052/Ecclesiastical_Fans_(Exapterigo)). The liturgical fans and processional cross are from the Church of St George, Gümüşhane (Plate 7). The fans were donated in 1729 by master miner Konstantinos Zilfis (Benaki Museum Athens display).

1827 Parcel-gilt silver ciborium, St George Church

A ciborium is a vessel for holding Eucharist bread to be delivered during a church service. The parcel-gilt silver ciborium dated 1827 was donated by Silvestros, metropolitan of Chaldia to the Church of St George, Gümüşhane (bottom left in Plate 7; Plate 8) (www.benaki.org/index.php?option=com_collectionitems&view=collectionitem&Itemid=&id=143003&lang=en).

Plate 6: Silver dish, Church of the Annunciation, Trabzon, 1802 (author’s photo 2024, Benaki Museum, Athens)

Plate 7: Liturgical fans (1729) and processional cross, St George Church Gümüşhane (author’s photo 2017, Benaki Museum, Athens)

Plate 8: Ciborium, St George Church Gümüşhane, 1827 (Benaki Museum, Athens (Source)

1700 Benedictory Cross, Choutoura Monastery

The foremost monastery in Chaldia was Choutoura. It was probably founded before 1461. The benedictory cross of carved wood mounted in silver-gilt and enamelled frame is dated to 1700 (Plate 9). The mount has polychrome enamels, pearls and semiprecious or paste gems. The inscription on the body reads, ‘Akakios, hieromonk of Choutoura Monastery, 1700’ (Ballian 2002:347).

1745 Pair of liturgical fans

This pair of liturgical fans from Gümüşhane, 50 cm high and 32.5 cm in diameter were made by Ioannis, son of Georgios Konstatas. They are made of parcel-gilt silver, niello and glass paste (Plates 10–11). The fans were donated in 1745 to the Church of the All Holy Theotokos Kaniotissa by the archbishop of Chaldia, Ignatios Kouthouris, for the salvation of his parents. The Virgin Kaniotissa is the Church of the Dormition of the Virgin in Gümüşhane (Ballian 2011:94).

Plate 9: Benedictory cross, Choutoura Monastery, Chaldia 1700 (Benaki Museum, Athens, Ballian (2002: 347))

Plate 10: Liturgical fan, Church Holy Theotokos Kaniotissa, Gümüşhane (Benaki Museum, Athens, Ballian 2011:95)

Plate 11: Liturgical fan, Church Holy Theotokos Kaniotissa, Gümüşhane (Benaki Museum Athens, Ballian 2011:95)

1712 Cover for New Testament

This rare edition of the New Testament was printed in 1563 with a cover measuring 15.8 cm by 10.6 cm made in 1712 of silver gilt with wooden end-boards (Plate 12). Its gilded cover was the work of the goldsmith in Transylvania, Sebastian Hann. This New Testament was [believed to have been] donated to the St George Church in Gümüşhane by Soumelites Zamanos in 1726 (Ballian 2011:222)

Plate 12: Cover for New Testament, 1712, silver guilt (Benaki Museum Athens, Ballian 2011:223)

Conclusion

It is clear the devotion to Christianity by the Orthodox Pontic Greeks in Chaldia by the large collection of churches and monasteries that they built. Unfortunately, the churches are now in ruins and some should be renovated in order to foster tourism. The photographs in this paper give a glimpse into the number of church silverware that has been preserved. While many church artefacts were preserved, many artefacts were unable to be removed from Anatolia and were buried or burnt near their churches.

Notes

Note 1

The Exchange of Orthodox and Muslim Populations between Greece and Turkey was under the Lausanne Convention (January 1923). Most of the Greeks in Istanbul (i.e. those who were established before 30 October 1918) were exempt from this exchange and an equivalent number of Muslims in western Thrace. The Orthodox Christians on the islands of Imbros and Tenedos in the north-eastern Aegean Sea were also exempt as specified in the wider Treaty of Lausanne signed in July 1923 (Hirschon 2003:8).

Note 2

In 1854, Humphry Sandwith arrived in the neighbourhood of Gümüşhane. He was told that there were 36 mines of which 10 to 14 extracted copper, while the rest extracted lead (which also contained silver). Sadly, these mines had failed to take advantage of modern inventions. The smelters produced 300 kg of lead which also yielded 0.6 kg of silver (and every 710 gm of silver would also produce 28 gm of gold). The furnace produced about 227 kg of lead every 10 days (Sandwith 1856:35–36).

Bryer (1982:138) interpreted Hamilton’s (1842) calculations in 1836 of an operating silver-lead mine, near Gümüşhane. It took very roughly, 260 tons of timber to produce 65 tons of charcoal to roast about 1.8 tons of lead ore which yielded 15.4 kg of silver and 0.45 kg of gold.

Acknowledgements

I warmly thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

Ballian AR (1995) Patronage in central Asia Minor and the Pontos during the Ottoman period: the case of church silver, 17th – 19th centuries, PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, England.

Ballian A (2002) ‘Argyroupolis—Gümüşhane: mining capital of Pontos’,:339–349 in Koromila M (ed) (2002) The Greeks and the Black Sea: from the Bronze Age to the early 20th century, The Panorama Cultural Society, Athens.

Ballian A (2011) ‘Relics of the past: treasures of the Greek Orthodox church and the Population Exchange’, in Ballian A (ed) (2011):37–57, 82–115.

Ballian A (ed) (2011) Relics of the past: treasures of the Greek Orthodox church and the Population Exchange, the Benaki Museum collections, (in English and French), Benaki Museum, Athens.

Bryer AAM (1982) ‘The question of Byzantine mines in the Pontos: Chalybian iron, Chaldian silver, Koloneian alum and the mummy of Cheriana’, Anatolian Studies, 32:133–150.

Bryer A (1983) ‘The crypto-Christians of the Pontos and consul William Gifford Palgrave of Trebizond’, Theltio Kentrou Mikrasiatikon Spoudon [Bulletin Centre for Asia Minor Studies] Athens, 4:13–68, 363–65.

Bryer A (1991) ‘The Pontic Greeks before the diaspora’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 4(4):315–334.

Bryer A (2009) ‘Last judgements in the empire of Trebizond: painted churches in inner Chaldia’,:519–551 in Shukurov R (ed) Mare et litora, (Essays presented to Sergei Karpov for his 60th birthday, Indrik, Moscow.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1970) ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes, part 3’, Archeion Pontou, [Archives of Pontos], 30:228–375.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Bryer A, Isaac, J and Winfield D (1972–1973) ‘Nineteenth – century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes, part 4’, Archeion Pontou, [Archives of Pontos], 32:128–310.

Delivorrias A (2011) ‘Foreword’,:10, in Ballian A (ed) (2011).

Hamilton WJ (1842) Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia: with some account of their antiquities and geology, 1, (originally published by John Murray, London), reprinted 2009.

Hirschon R (2003), “Unmixing peoples’ in the Aegean region’,:3–12 in Hirschon R (ed) (2003) Crossing the Aegean: an appraisal of the 1923 compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey, Berghahn Books, New York.

Sandwith H (1856) A narrative of the siege of Kars, (3rd ed), John Murray, London.

Talbot Rice D (1929–30) ‘Notice on some religious buildings in the city and vilayet of Trebizond’, Byzantion, 5(1):47–81.

Topalidis S (2024) ‘A survey of churches in inner Chaldia, Pontos’, at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/860-a-survey-of-churches-in-inner-chaldia

Zachariadou EA (1979) ‘Trebizond and the Turks (1352–1402)’, Twelfth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies: The Byzantine Black Sea, Birmingham England, 18–20 March 1978, Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos], 35:333–358.