Sam Topalidis 2022

Introduction

This paper describes the American Protestant missionary movement1 in Anatolia within the Ottoman empire, with a focus on its mission at Merzifon (Marsovan) (1863–1921) south-west of Samsun (Figure 1) in Pontos.2 (Note 1.)

These missionaries performed selfless work to benefit the lives of local people, initially through education and later to include medical care. They did not wish to challenge the existing social order. Their goal was to bolster their particular form of Christian faith, but over time their approach shifted to include a more secular curriculum which focused on the fundamentals of Western secondary schooling and vocational training. Bible studies continued to be included as part of their teaching. These missionaries in Anatolia relied on financial contributions from overseas to help maintain their work.3

Figure 1: Settlements from Sinope to Trabzon in north-eastern Anatolia (scale: 85 km from Samsun to Merzifon).

Merzifon was a substantial American mission station in Anatolia, with its Anatolia Boys’ College, other schools, including an orphanage, a hospital and other buildings which collectively looked more impressive than the town of Merzifon. The mission station was forced to close by the Ottoman Turks in 1921. The Anatolia College re-opened in 1924 in Thessaloniki in Greece and is still operating there today.

Tanzimat Reforms

The Tanzimat period of legislation and reform by the Ottoman sultans (1839–1871) included educational, economic and other law reforms. In 1844, the death penalty for renouncing Islam was abolished.4 Then in 1856, a new reform charter, Hatt-i Hümayun, proclaimed the principle of freedom of religion in the Ottoman empire5 and this contributed in the dissemination of Protestantism in the empire. However, in 1874, the Ottoman government outlawed the conversion of Muslims to Christianity.6

American Missionaries in Anatolia

In the early 19th century, missionary societies were established in the United States to spread their evangelical mission to the world. This had much to do with the revised approach of the so-called religious revival, the ‘Second Great Awakening’, to an individual’s role in his or her own salvation and destiny and a new sense of social responsibility.7 Imbued with a social purpose, some men and women were inspired to travel to spread the Gospel around the world. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) developed into the most active missionary organisation in Anatolia.8

In 1819, American missionaries began working in the Ottoman empire. In order to convert people to Protestantism, they used education to infiltrate Ottoman society.9 Turkish officials prevented them from trying to convert Muslims, so the missionaries then focussed on converting Armenians and Greeks to Protestantism. The first Greek Evangelical community was established in 1867 in north-west Anatolia.10

The Greek Orthodox church and the Gregorian Armenian church [sometimes called the Armenian Orthodox church or the Armenian Apostolic church], respectively, fiercely resisted Protestant attempts to convert their Greek and Armenian congregations.11

The relations between the members of Orthodox and Protestant denominations were not always bitter. One of the places where Orthodox and Gregorian churches had positive attitudes toward Protestants was Merzifon where the good work of the American schools on the campus and the American hospital created a relatively peaceful atmosphere.12

During the reign of Ottoman sultan Abdulhamid II (1876–1909) the first Ottoman attempts to limit Christian missionary activities began. However, the Ottoman administration had difficulty in closing missionary schools and most opened without a licence.13 Interference by foreign powers also inhibited Ottoman efforts to limit missionary activities. These American institutions provided a modern education and, to their credit, prepared students for life after school.14

The missionaries saw the difficult life of women in Anatolia who were basically treated as servants. They were denied education and obliged to marry in early adolescence. Young wives were commonly denied permission to speak to anyone [at least in their household] but their husband until after the birth of a first child. The Eastern family, based upon female submission, appeared to the missionaries as a priority for reform. Educating women was seen as possibly a profound opportunity for shaping the behaviour of mothers and home life. However, given the Ottoman social segregation, this meant that access to the female population was possible only for women missionaries.15

Merzifon

Merzifon is located in the central Black Sea region in the Amasya province, in Anatolia, 46 kilometres north-west of Amasya (Figure 1). Located between Erzurum and Istanbul, it had an important geographical location to connect to the Black Sea coast and inner Anatolia.16

Merzifon had seen Protestant missionaries as early as 1852. Three out-stations were occupied in 1862 (Amasya, Samsun, Avkat (near Chorum)) and two more in 1863 (Hadjikeuy (near Amasya) and Vizir Keopreu (around 40 kilometres north of Merzifon)). The other out-stations were occupied in the following order: Charshambah (east of Samsun) in 1865, Unye (on the Black Sea coast) in 1866, Chorum in 1867, the Kapoo Kaya villages in 1869, Herek in 1873, Zile (south of Amasya) in 1876, Gumush and Azabaghin in 1878, Bafra and Kastamoni (200 kilometres north-west from Merzifon) in 1880, Dere Keuy (up to 45 kilometres north-west from Merzifon) in 1884, Ooloo Puar in 1885 and Alacham (north of Merzifon near the Black Sea) and Fatsa in 1886 (Figure 1). Of these locations, 14 were towns and the rest were villages.17

In 1867, Merzifon was a Turkish and Armenian settlement.18 The Turkish and Armenian communities occupied separate neighbourhoods living in sun-dried brick dwellings. The area around Merzifon produced an economy based upon the production of grains, supplemented by fruits, nuts and vegetables and a small yarn industry. The main access to Merzifon was through the Black Sea port of Samsun (Figure 1). From there, a three-day ride by horseback took travellers [105 kilometres south-west] to Merzifon, situated to the east of the Kizilirmak River. The trip from Istanbul via Samsun required at least a week (depending on the weather). The alternative overland route by horseback from Merzifon to Istanbul of rugged terrain was far slower and more dangerous due to the prevalence of bandits. Merzifon’s physical environment was comparatively healthy, owing to its almost 800 metres elevation with a flat topography on the southern foothills of the Pontic Mountains and its dry climate.19

The Merzifon American campus comprised 16 hectares on the northern edge of the town, just outside the town’s walls.20 The American Protestant mission was enclosed by a mud brick wall about 3 metres high with three gates.21 It attracted primarily Armenian and Greek Christian girls and boys (including those who had ‘small means’) whose parents were eager to improve their children’s fortunes through education and practical training. Because the conversion of Muslims to Protestantism was forbidden, most Turks kept their distance from the campus.22

In the mid-19th century, there was practically no Greek community in Merzifon. Gradually, a few Greeks came to Merzifon for business and constructed a humble Greek Orthodox church. Later they began to maintain Greek schools and the community grew.23

In 1881, the Preparatory School became the Merzifon Boys’ High School on the American campus with a course of four years in addition to a preparatory course of one year. The Theological Seminary was separate, its course extending to three years and confined to theological studies. In 1886, the Boys’ High School had its course of study extended and its name changed to Anatolia Boys’ College.24

Boys entered the high school (at the minimum age of 12 years) following exams in their native language, Turkish, geography and arithmetic. Most did not know English, so emphasis was placed on preparing them for the English curriculum. By their fourth year, graduates received a certificate valid for entry to the Anatolia Boys’ College.25

In 1887, the Protestant church on the American campus at Merzifon accommodated 1,000 people who met weekly for public worship.26 In 1894, the new Girls’ School building was erected.27

1895 Armenian massacre

The last decades of the 19th century saw the emergence of an Armenian national movement. This development alarmed Ottoman sultan Abdulhamid II, who suppressed separatist sentiments. The Hamidian massacres were a series of atrocities carried out by Ottoman forces and Kurdish irregulars against the Armenians in the Ottoman empire between 1894 and 1896. A wave of killing occurred in September 1895, when the Ottoman authorities’ repression of an Armenian protest in Istanbul turned into a massacre. The incident was followed by a series of massacres in towns with Armenian communities that culminated in December 1895.28

On 15 November 1895, in the town of Merzifon, Dr Tracy (President of the Anatolia College) reported that, starting at noon and lasting for 4 hours, a Turkish mob had massacred Armenians and looted their property. About 125 men were killed. Luckily, the American Protestant campus outside the town walls was spared. Many frightened people flocked for protection to the campus. At about 4 pm, the Ottoman governor with around 40 soldiers came to protect the campus.29 Dr Tracy added that he saw 90 dead bodies the next morning outside the American campus walls. From that day, most of the Armenians remained in their houses and business came to an end and the government distributed bread rations to the needy. Day scholars had been stopped from attending classes at the American campus, although there were still nearly 130 boarders in College.30

Prior to World War I

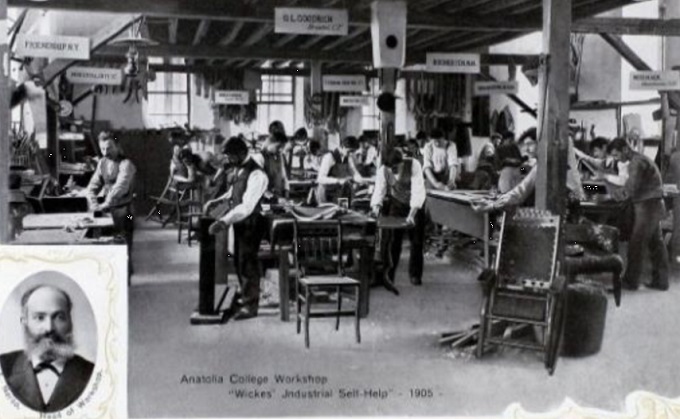

In 1898–1899, there were 246 (191 Armenian and 55 Greek) students in the Anatolia Boys’ College and the Boys’ High School. Nearly one third of all the students met their expenses (to some extent) by their labour in the Self-Help Industrial Department (Plate 1).31

The Self-Help Industrial Department offered the youth at the campus the opportunity to work their way through their education. Departments such as a joiner’s house, bindery, shoemaker, tailor and trial farm were established in order to allow poor students to earn money. These departments also provided the students a professional job. Each student acquired a trade and the products of their labour were sold.32 Girls in the high school and the orphanage were involved in weaving, e.g. the manufacture of narrow gingham cloth.33

At the beginning of the 1900s, many American mission stations in Anatolia had mission hospitals. These medical missionaries frequently organised medical tours to areas without hospitals to meet the needs of the missionary personnel. These mission hospitals also engaged with a large non-Muslim as well as Muslim clientele.34

The Merzifon campus was a place of high activity, developing services as it expanded during the pre-war years. Indeed, many people from the surrounding villages came to the Merzifon campus for medical help.

Plate 1: Self-Help Shops for boys,1905 (Özerol and Akalin 2019:38).

Reports indicated that they were very grateful and did not leave without hearing a good deal of the Bible.35

In 1913, the Anatolia Boys’ College on the Merzifon campus listed 32 staff: 11 Armenians, 10 Americans, nine Greeks, one Swiss and one Russian. During the year, 425 students were enrolled in the four College and four Boys’ High School classes, which included 200 Greeks, 160 Armenians, 40 Russians and 25 Turks. There were 275 pupils in the Girls’ School and about 100 patients at any one time in the hospital. Missionary families, teachers and their households, employees, students and others, brought the number of people on the entire campus to around 1,000 souls.36

The Girls’ School was a finishing school [including teaching young girls social graces] at approximately high school level. In between the Girls’ and Boys’ schools was the highly regarded School for the Deaf. Near the Anatolia Boys’ College a large new hospital was being completed. In addition, was one of the few nurses’ training schools in Anatolia. At the lower end of the campus was the Theological Seminary, for preparing young men to become pastors in the Protestant churches throughout Anatolia. For students, attending the American-sponsored schools was a great privilege.37

The Girls’ School was originally designed to prepare future pastors’ wives, but its goals broadened to include education which had been formerly restricted to males. The prevalence of marriage in the mid-teens for females and the rarity of employment outside of the home led most girls to leave before graduating. From 1910, the preparatory years were increased to four years to accommodate girls who would not continue to the four-year high school. At the same time, the Department of Domestic Science was introduced to teach cooking, sewing, and dressmaking.38

On the campus, promising young graduates were employed as teachers. They were also assisted to take advanced courses in Europe or America to prepare for permanent service. In this way men became masters in their respective departments of instruction, leaders of their people, authors, lecturers and preachers of renown.39

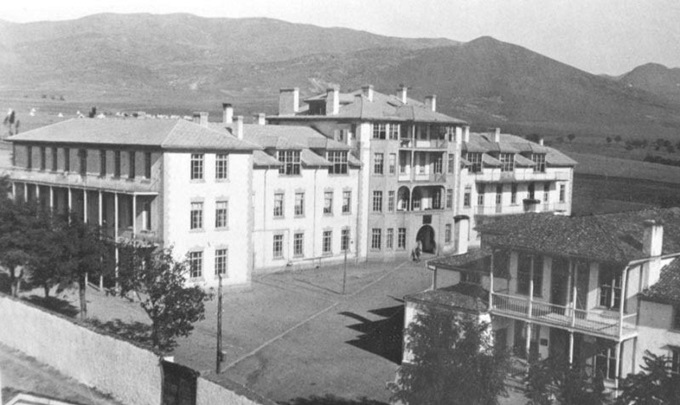

In Anatolia, the American missionaries were vulnerable to unfamiliar diseases and poor sanitary conditions. In response, the missionaries made health concerns an extension of their calling.40 The new American campus hospital buildings at Merzifon were completed in 1914 (Plate 2).41 By 1914, the town of Merzifon had an assumed Armenian population of 10,400.42

Plate 2: American campus hospital at Merzifon, (completed in 1914) (Özerol and Akalin 2019:37).

A new library-museum building on the campus was occupied in 1914. The museum had over 6,000 objects and was usually visited by 200 people each week. The library contained 6,000 volumes. The reading room was also patronised by Orthodox Greeks, Armenians and Turks. The Anatolia College’s influence was felt in the Protestant, Orthodox Greek, Armenian and Turkish Schools in the town.43

The Girls’ School reached capacity by this time and had also received its first Mohammedan girls as boarders.44 By 1915, some of the buildings in the Merzifon American campus included:45

- a Boys’ College Boarding School

- a Girls’ Boarding School (Plate 3)

- the three storey North College (Plate 4), of the Anatolia Boys’ College

- a library-museum (three-storey high)

- the Kennedy Home (for boys), the Boys’ High School and the Superintendent’s house

- Union Hall

- Self-Help Shops

- White Hall

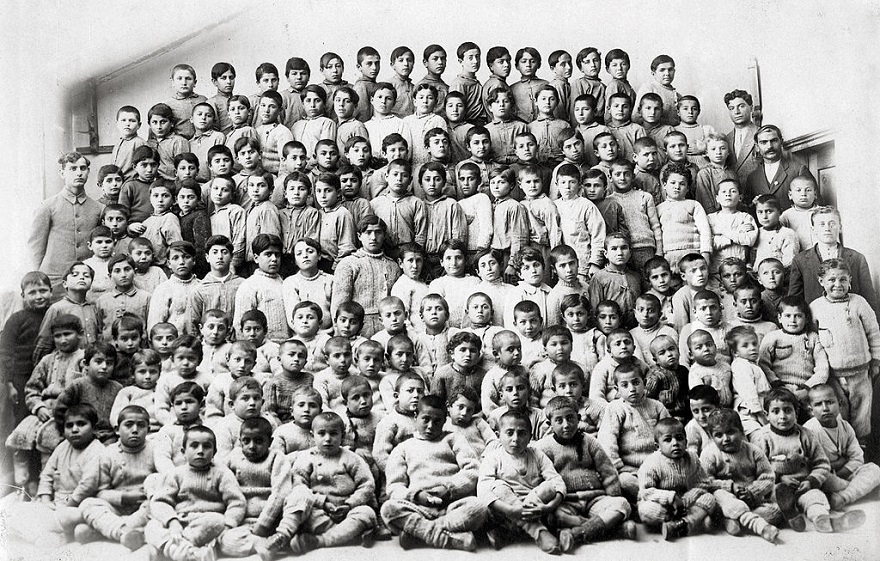

- a boys’ orphanage (Plate 5)

- a new hospital (Plate 2)

- 11 Armenian houses

- the school for the deaf.

Plate 3: The opening of the Merzifon campus Girls’ Boarding School, 1894 (https://ozhanozturk.com/2018/01/07/merzifon-amerikan-koleji-pontusculuk/).

Plate 4: The North College [part of the Anatolia College], 1890s (Özerol and Akalin 2019:29).

1915 Armenian genocide

In March 1915, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP),46 the real arbiter of Ottoman politics, decided to annihilate the Armenians in the Ottoman empire in what is called a genocide.47

Shortly after the schools closed in June 1915 for the summer vacation on the Merzifon campus, the Ottoman government announced that all Armenians were to be deported to remote places in the interior of Anatolia.48

Plate 5: Armenian boys at the Merzifon campus orphanage, 1918 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Armenian_Orphans,_Merzifon,_1918.jpg).

On 9 August 1915, the deportation of the Armenians from the town of Merzifon was in full swing. On 10 August, the local Ottoman governor announced that the Armenians swarming into the American Merzifon campus also were to be deported. The next day the Merzifon campus was surrounded by armed soldiers and all Armenians were removed from the buildings. (There were 72 people taken from the campus, including the hospital.49) The women and little children were loaded onto carts clutching bundles of food and clothing. The few men and older children trudged along beside them on the journey. On the second day, the men were shot and buried in a mass grave. The soldiers had not entered the Girls’ School on the campus where the Armenian students, with some of their teachers, had taken refuge. Two days later, wagons accompanied by armed soldiers loaded these [63] girls into carriages and they were taken away. Subsequently, the governor permitted teachers Miss Willard and Miss Gage from the girls’ school [true heroines] to follow after the girls. Due to the intervention of Henry Morgenthau, the American Ambassador at Istanbul, (Willard, Gage and others), [most of] the girls and the two teachers were able to eventually return safely to Merzifon.50

When the killing of the Armenians was over, only a few hundred of over 10,000 Merzifon’s Armenians were left alive.51 From the Protestant community in the town, 900 of the 950 souls had been swept away.52

1916 closure of the American campus

In early 1916, the north-east region of Anatolia near the Black Sea was occupied by the Russian army. The Black Sea coast from just east of Tirebolu, past Trabzon (Figure 1) to the Georgian border was in Russian hands.

In May 1916, the American campus of Merzifon was surrounded by police and gendarmes [soldiers acting as armed police]. The Ottoman town leader announced that America had declared war against Germany [actually, America declared war against Germany in 1917] and would soon do the same against the Ottoman empire. He then declared the schools closed and all Americans (10 adults and four children) were to leave for Istanbul. [He had taken possession of the campus which was to be used as a military hospital.] About two months later, permission was granted for five of the Americans (Dana Getchell and his wife of the Anatolia College, Charlotte Willard, principal of the Girls’ School, Frances Gage of the International Young Women’s Christian Association and Miss Zbinden, the Swiss lady in charge of the orphanage) to return to the Merzifon campus. On the campus there were thousands of Ottoman soldiers suffering from typhus, smallpox and other illnesses.53

The five missionaries were not allowed out of the campus so they may not have witnessed any Greek deportations from the town of Merzifon from late 1916 to early 1917—a process which had occurred elsewhere near the Russian army front.

1919 Reopening of the College

During World War I, the Merzifon campus Girls’ School remained open. In March until late September 1919, the town of Merzifon was occupied by British troops.54

For nearly three years, up to 1919, the American campus was used as a military hospital. In March 1919, the campus hospital was handed over to the American charity organisation, Near East Relief to be used as a centre for relief work.55 The campus reopened on 1 October 1919. Only four teachers and two employees remained to rejoin the staff.56 At this time, church services on Sunday usually received a congregation of at least 600 people in the Protestant church on the campus.57 When the campus reopened there were 166 boys in the high school and approximately the same number of girls in the girls’ school. In addition, the campus also housed some 600 Greek and Armenian war orphans (Plate 5). There was also a ‘Baby House’, where about 30 Armenian girls who had been rescued from their Turkish abductors were living with their babies.58

1921 Christian genocide

In September 1920, the schools opened on the campus with more pupils than had been enrolled in the previous year. Up to February 1921, there were about 200 students in each of the schools and nearly 500 orphans on the campus. In February 1921, the Turkish teacher from the campus was murdered on his way home.59 The Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) was still waging in western Anatolia.

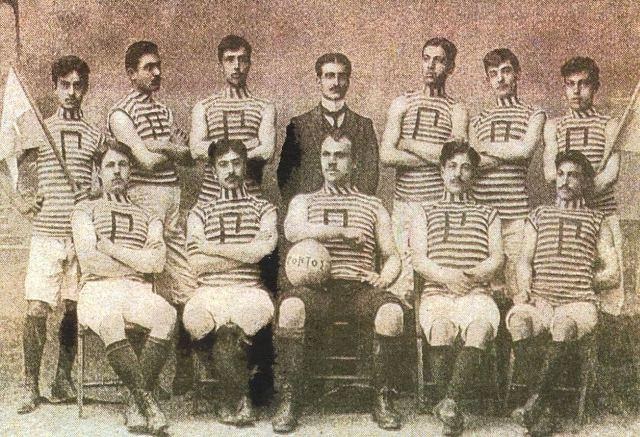

On 18 March 1921, General Jemil Jahid came with Ottoman soldiers to the American Merzifon campus and announced that evidence had been found of a Greek revolutionary plot centred on the American campus and as a consequence, the buildings were to be searched. They wanted to find arms, ammunition and incriminating papers. In fact, they only found the following three items which they considered (falsely) to be evidence of subversive activities:

- A historic map of St Paul’s missionary journeys where an area of Anatolia was labelled Pontos. They claimed that this was evidence that the Greeks were planning to reclaim this area.

- The list of officers in the Anatolia College Greek Literary Society.

- A black and white picture of a football team whose players wore striped shirts (Plate 6). The investigators claimed that the shirts were blue and white, the Greek national colours. [It is believed that the real shirts were blue and white.]

As a result, late in March 1921, the institutions on the campus were closed and the Americans were told to leave Anatolia. However, the around 600 orphans on the campus could remain with the local staff. The missionaries, Don Hosford, Carl Compton and his wife Ruth were permitted to stay to look after the orphans and the campus property. They were not permitted to conduct regular schooling and their chief activities for the orphans were both recreation and training in trades. The Near East Relief organisation had brought in quantities of raw materials for use in relief industries. The boys’ industries were carpentry, metal work, tailoring, and shoe making; the girls’ industries were weaving, sewing, knitting, embroidery, and pattern making.60

Apparently, the three Americans were selected to stay in Merzifon because they could not speak Turkish. Compton allowed the young Couzinos (a Greek) to stay and act as a Turkish interpreter and Couzinos’ sister became the head of the orphanage clinic.61

Retributions continued to be served. The Pontos Club, the College Greek literary and athletic club had meetings on Saturday nights.62 Its leaders, four teachers and two students, were charged with subversion and sent to Amasya and hanged.63 Mr Pavlides, pastor of the Greek Protestant Church in Merzifon town, suffered the same fate.64

When the Greeks of Merzifon were made aware that Topal Osman [a notorious Turk from Giresun who with his followers were responsible for many atrocities in Pontos] was coming to their town many fled to the safety of the mountains.65 A massacre of Christians in Merzifon began on 23–24 July 1921 when Topal Osman and his brigands rode into town. They spent four days pillaging and killing. This carnage was followed by several days of murder at the hands of local Turks, assisted by gendarmes and troops. Hundreds of Greeks and Armenians from the town fled for protection to the Merzifon campus.66

Plate 6: Merzifon, football team of the Hellenic Athletic Club – Pontos 1906 (Fotiadis 2019:657) (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/72/Pontus_Greek_Soccer_Team.JPG).

Subsequently, the governor of the province arrived in Merzifon and put a stop to Topal Osman’s killings. Topal Osman’s actions were reported to Ankara, whereupon he was ordered to proceed to Ankara.67 After nearly a week of terror, Topal Osman came to the Merzifon campus and requested to be driven to the next town. Don Hosford drove him and that same evening Hosford and the truck returned safely.68 Mr Hosford summarised the massacres at Merzifon as follows:

… there was no distinction in the treatment between Greeks and Armenians. From a Christian population of 2,000 to 2,500, almost all the men were killed. Women and children were also killed, in all upwards of 700. All [the remaining] Greeks were deported. About 700 Armenians were left in the town … Every Christian house was looted and 400 houses were burned. ... Repeated tales of the utmost cruelty were borne to us, such as the burning of churches with Greeks inside.69

Opening of the Anatolia College in Thessaloniki

Late in July 1922, the charitable Near East Relief organisation [which took over the operation of the hospital in 1919] sent new workers to the Merzifon campus. Compton and his wife, Ruth, then left for Istanbul where Compton called on Admiral Bristol,70 acting US High Commissioner, to inform him about events in Merzifon. To Compton’s surprise, Bristol was very sceptical about his reports of a massacre.71

Following the forced closure of the schools on the Merzifon campus [the orphanage on the campus was still operating] by the Turkish government in March 1921, the Anatolia College relocated to Thessaloniki, Greece in 1924. The Greek Prime Minister, Venizelos, had encouraged the President of the Anatolia College to re-open the College there in order to serve Thessaloniki’s burgeoning educational needs which resulted from the massive influx of Anatolian refugees.72

A large number of Greek and Armenian refugees from the Merzifon area had resettled in Greek Macedonia [after the end of the Greco-Turkish War in 1922 and the 1923 Exchange of Populations between Greece and Turkey]. Public schools were overcrowded. In March 1925, Compton and his wife Ruth returned to Thessaloniki, Greece to resume work at the Anatolia College. They were not overly troubled by the rather crude buildings and the inadequate equipment. In early 1926, it was decided that the Anatolia College should make its permanent home in Greece. It was then necessary to dispose of the equipment left behind in Merzifon. That summer, Compton and his wife went to Merzifon to ship the items wanted in Thessaloniki and to sell off the rest. Sometime later, the Merzifon buildings and grounds were sold to the Turkish government, which used them for a military school.73

Today, the Merzifon site is used as a high school.

Note 1

Major dates in the American campus at Merzifon (based on McGrew 2015:405–406).

1863 ABCFM establishes a missionary station at Merzifon.

1865 Theological Seminary and Girls’ School move to Merzifon.

1881 Opening of the Boys’ High School at Merzifon.

1886 Opening of the Anatolia Boys’ College.

1894 The new Girls’ School building erected.

1895 Massacres of Armenians at Merzifon.

1897 Hospital established at Merzifon campus.

1910 School for the Deaf established.

1914 New Anatolia College Hospital building completed.

1915 Genocide of Armenians.

1916 American campus at Merzifon closed by Ottoman government.

1919 The Near East Relief charitable organisation reaches Merzifon. Re-opening of the American campus.

1921 Merzifon campus closed by the Turkish government.

1921 Deportations and executions of Armenians and Greeks from Merzifon.

1922 (August) Greek army is defeated in the Greco-Turkish war in western Anatolia. Greeks begin to be forced out of Turkish territory for Greece.

1923 (January) Lausanne Convention – Exchange of Populations between Greece and Turkey.

1924 Anatolia College reopens in Thessaloniki, Greece.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Russell McCaskie and Michael Bennett for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

1. The Protestant doctrine believes in direct communication with God, basing its faith upon the authority of the Scriptures alone. Protestants object to the adoration of saints, the use of icons and other images, excessive rites and ceremonies, toleration of alcohol and a casual attitude towards respecting the Sabbath as a day of rest (McGrew 2015:17).

2. Pontos is the north-east corner of Anatolia adjacent to the Black Sea coast. Protestant missionaries were present in Merzifon in 1852.

3. McGrew (2015:xv).

4. Zürcher (2017).

5. Konstantinou (2020).

6. Shaw and Shaw (2002).

7. The Evangelical church is any of the classical Protestant churches or their offshoots but especially, since the late 20th century, churches that stress the preaching of the gospel of Jesus Christ, personal conversion experiences and active evangelism (the winning of personal commitments to Christ) (www.britannica.com/topic/Evangelical-church-Protestantism).

8. Erol (2018:337–338).

9. McGrew (2015).

10. Göktϋrk (2015).

11. McGrew (2015:17). By the end of the 19th century, 10 Greek Evangelical churches were founded in Pontos and 11 in the rest of Anatolia (Konstantinou 2020).

12. Göktϋrk (2015:229).

13. An imperial license was finally granted to the American College in Merzifon in April 1895 (Sahin 2011:110).

14. Avaroğullari and Yildiz (2015:59).

15. McGrew (2015:63).

16. Özerol and Akalın (2019).

17. The Missionary Herald (October 1891:403). It is important to remember that the American Civil War was raging from 1861 to 1865 and in 1877 (April)–1878 (March) the Russo-Turkish War was fought in the Balkans.

18. White (1918).

19. McGrew (2015:33–34).

20. Özerol and Akalin (2019).

21. Compton (2008:64).

22. McGrew (2015:xv–xvi).

23. In addition, the St Basil’s Club was founded by the community in the town to further the education and enlightenment among the Greek Orthodox population, of which there were about 500 in the town [1912] (The Missionary Herald, March 1912:131). In 1870, Merzifon had 150 Greek families (Ioannidis (1870) in Lazaridis (1988:53)).

24. The Missionary Herald (May 1899:185).

25. McGrew (2015:112).

26. The Missionary Herald (January 1888:20). According to The Missionary Herald (October 1891:405), at the Merzifon American campus there were 767 Protestants in 1870 and 3,025 in 1890.

27. The Missionary Herald (May 1899:186). In February 1893, the three storey girls’ school which was being built was set on fire. Corrupt Turkish authorities were implicated in the fire. The Ottoman government paid 500 Turkish liras (US$2,200) compensation for the fire (The Missionary Herald, June 1893:225).

28. www.britannica.com/topic/Hamidian-massacres

29. White (1918:35).

30. The Missionary Herald (March 1896:106).

31. The Missionary Herald (May 1899:187).

32. Özerol and Akalin (2019:38).

33. Maksudyan (2010).

34. Yücel (2015:61, 64).

35. The Missionary Herald (December 1900:530).

26. White (1918:67).

37. Compton (2008:65).

38. McGrew (2015:117–118).

39. White (1918:23–24).

40. McGrew (2015:92–93).

41. Özerol and Akalin (2019:36). In 1897, the hospital on the campus began its career (White 1918:50). In 2005, the hospital building, which was transferred to the Turkish Ministry of National Education, [and then repaired] has been functioning as Merzifon Science High School since 2010 (http://informadik.blogspot.com/2014/06/).

42. Armenian Patriarch census (Kévorkian 2011). It is unknown how many Turks lived in the town.

43. The Missionary Herald (October 1914:455).

44. The Missionary Herald (April 1914:180).

45. Özerol and Akalin (2019:26).

46. The Young Turks led a revolutionary movement against the Ottoman sultan and they established a constitutional government. They promoted the modernisation of the Ottoman empire and a new spirit of Turkish nationalism. The influential Young Turk organisation known as the CUP advocated a program of reform. The actual impetus for the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 came particularly from discontented members of the Ottoman 3rd Army Corps in Macedonia. This revolutionary group merged with the CUP in 1907. In 1908, the 3rd Army Corps led a revolt against the provincial authorities throughout the Ottoman empire. The Young Turks took effective control of the government in 1913 when the CUP under the triumvirate of Talat Pasha, Cemal Pasha, and Enver Pasha, set themselves up as the real arbiter of Ottoman politics (www.britannica.com/topic/Young-Turks-Turkish-nationalist-movement).

47. By March 1915, most Armenian soldiers in the Ottoman army had been disarmed and moved into [the dreaded] labour battalions (Morris and Ze’evi 2019).

48. Compton (2008:67).

49. Şahin (2018:57).

50. Compton (2008:69–70). Within two days the two teachers were able to catch up with most of the girls (22 girls had been detached from the original group and sent with exiles from other places—they perished). They brought back 41 of the original 63 girls who were taken away. This involved Miss Willard bribing Turkish officials (The Missionary Herald, December 1915:581).

51. Morris and Ze’evi (2019:189). Although it is believed that most Armenians were murdered, there may have been only a few hundred left alive in the town.

52. White (1918:71–72). An accurate number of all the people in Merzifon is unknown.

53. The Missionary Herald (March 1920:116–120).

54. In June 1919, there were 80 British troops at Merzifon (Özerol and Akalin 2019:42). By late September 1919, the British forces had withdrawn from Samsun and Merzifon (Mango 2002).

55. Compton (2008:88). The Near East Relief was the American charity formed in 1915 as a result of USA Ambassador at Istanbul, Henry Morgenthau’s request for aid for the Armenians who had been massacred and deported in Anatolia (https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/near_east_relief).

56. The campus was evacuated by the Ottoman army in early April 1919 (The Missionary Herald, September 1920:405). In May 1919, the Greek army landed at Smyrna on the west coast of Anatolia.

57. The Missionary Herald (October 1919).

58. Compton (2008:88).

59. The Missionary Herald (June 1921:216).

60. Compton (2008:89–90).

61. Couzinos (2010:107).

62. Couzinos (2010). Athletics for students became an important part of school life (McGrew 2015).

63. McGrew (2015:xvi).

64. Compton (2008:94).

65. Fotiadis (2019:400).

66. Morris and Ze’evi (2019:412).

67. Shenk and Koktzoglou (2020:229).

68. Compton (2008:94).

69. Meichanetsidis (2015:133).

70. Admiral Mark Bristol was the top American representative in Turkey during August 1919–1927. Bristol, wishing to aid American business interests in Turkey was more sympathetic to the Turks than to Turkey’s Christian peoples, despite the terrible sufferings of these groups during World War I and then by the Turkish Nationalist forces (Shenk and Koktzoglou 2020). Admiral Bristol has been severely criticised for his lack of assistance to the suffering Christians.

72. Compton (2008:97–98).

73. Compton (2008:8).

74. Compton (2008:115–116).