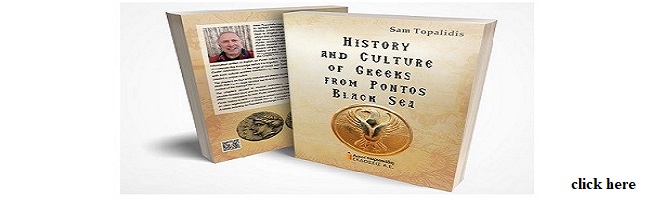

Figure 1 Tsabouna (tulum) bagpipe2

by Sam Topalidis (2014)

‘… ethnomusicologists should not only collect, safeguard or interpret music that was once performed, but they also need to advocate, to become active and responsible, in the sense of ensuring the preservation and future development of this musical practice …’ 8

1. Introduction

A bagpipe is sounded by reeds to which wind is fed by arm pressure on a flexible bag. This bag is kept filled with air from the mouth or from small bellows strapped on the waist and to the other arm. A bagpipe with only one pipe (e.g. the tsabouna (tulum) see Figure 1, played in Greece and Turkey) is rare, virtually all having at least two pipes. Of these, one pipe is the ‘chanter’ with fingerholes for playing melodies, and any others are usually ‘drones’ sustaining single notes.3 Chanters are either conical like an oboe and fitted with a double reed, or cylindrical, like a clarinet, often with a horn or horn-like extension fitted with a single beating reed. Drones are cylindrical and have beating reeds.15 Some are not as powerful in sound as the Scottish bagpipe: and are best heard in a small parlour.3

Bagpipes have been indigenous from the Atlantic coast of Europe to the Caucasus and from Tunisia in Africa to India. Of the over 130 different types of bagpipes played in the world (www.bagpipesociety.org.uk/international-bagpipe-day/), two kinds of bagpipe exist in Greece; the tsabouna (tulum), with a double chanter and no drone pipe, the main focus of this article and the gaida, with a single chanter and a drone.

After a brief history of the bagpipes, the primary focus of this article turns to a description of how the tsabouna bagpipe (called in the Greek context and tulum in the Turkish context) is constructed, how the tsabouna is played, its distribution in Turkey and Greece and its resurgence in contemporary communities. Reference is also made to the tsabouna in Pontic music from the Black Sea area of northeastern Turkey and the Pontic Greek refugees from this area who settled in Greece (note 1).

2. A brief history of the bagpipe

a) First recorded history

Little is known with certainty about the origins of the bagpipe. It is unknown how the instrument spread to so many countries. It probably originated on the Sumerian Plain, though sounding a reedpipe through an inflated skin may have occurred independently in Greece as inferred by Aristophanes in his play The Acharnians [425 BC]. Later in Rome, ‘utricularius’ (a bagpiper) is mentioned in Suetonius’s life of Emperor Nero [54–68 AD]. Greek historian, Dio Chrysostom [ca. 40– ca. 115 AD] notes the playing in Rome of an aulos (musical pipes sounded by a reed) with a bag under the arm.15 The early Roman bagpipe was probably an adaption of the bag principle used in Egypt for at least 100 years earlier as a bag-blown drone (without a chanter).6

b) Scotland

By the 14th and 15th century the bagpipe with chanter and a single drone must have been a familiar sight in England, Ireland and Scotland.6 Four types of bagpipe are associated with Scotland; the Highland pipe, the Lowland pipe, the ‘hybrid union pipe’, and the small-pipe. The Highland pipe has been a martial instrument from at least the 16th century. It has a sheepskin bag with three drones, (two tenor and one bass), a chanter and a blowpipe. The chanter has eight holes and a double vent-hole which is never stopped. The tone is exceedingly loud. Only the Highland pipe remains in regular use and has spread around the world.15

The Lowland pipe is bellows-blown with three drones. By the end of the 19th century, this type of bagpipe was no longer played. The hybrid union bagpipe was played in the 18th century and was best suited to playing indoors. The small pipe, rarely seen, is no louder than a violin.15

c) Ireland

The Irish bagpipe has taken two distinct forms: the mouth-blown war-pipe with two drones and the bellows-blown union pipe [often called Uillean pipes], suited only to indoor playing. The war-pipe in Ireland goes back to 1544 and in the 18th century it fell into disuse. The Scottish bagpipe began to be used in Ireland in the 19th century and in time the custom began of using a variant form with a single tenor drone instead of a pair.15 The Irish union pipe, which is played sitting, has existed from the end of the 17th century.4

d) England15

It appears that Northumberland is the main English county cultivating the bagpipe which formerly possessed three types (all inflated by bellows). They included the half-long pipe (now revived, may be identified with the Scottish Lowland pipe), the shuttle-pipe (which has died out) and the small pipe.

The Northumbrian small-pipe with three drones is an indoor instrument with the earliest known small pipe probably dates from the late 17th century. Around the middle of the 18th century, the end of the chanter was closed. It is the only closed chanter found on any bagpipe.

From 1928, the Northumbrian Pipers’ Society led a considerable revival of interest in playing the small-pipe. It also supports the playing of the half-long pipe. Long may the society continue.

e) France15

French bagpipes are of two types: bellows-blown and mouth-blown. The bellows-blown musette is a highly developed bagpipe which became fashionable during the 17th and the 18th centuries. Although the mouth-blown bagpipes have survived until modern times, the musette became extinct during the late 18th century. The origin of the musette, which appears to have been the prototype of the bellows bagpipe, was probably 16th century.

The cornemuse with blowpipe and chanter carrying a single treble drone, is now principally played by peasants. It has a conical chanter with eight open holes and an unstopped bell-hole. The biniou is the mouth-blown bagpipe of the Breton peasant with one drone. There are seven fingerholes and a double unstopped hole in the bell.

f) Spain and Portugal

In the northwestern provinces, Galicia and Asturias in Spain and northern Portugal the gaita continues to flourish.4 It resembles the Scottish Highland pipe though it usually has only one drone. The chanter has seven holes and a thumb hole, three vent-holes lower down and a double reed. The Catalan cornamusa has been extinct for a century, but the shepherds’ zampona of the Balearic Islands is still played.15

g) Northern Europe15

The German Bock, with a deep-sounding chanter and drone, was of the western Slav type and is played in the Böhmerwald.

A simple bagpipe [sackpipa] survives in the Swedish district of Dalarna. It has a cylindrical chanter with six holes and a thumb hole and two short drones. In certain islands and coastal districts of Estonia the bagpipe consists of a bag from a seal’s stomach, a cylindrical chanter with six holes and two drones. There are similar instruments in Latvia.

h) Belarus5

The duda bagpipe with a single drone was well known and widespread in the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century in what is now called Belarus. It all but disappeared after World War II, however, from the 1980s, it has enjoyed a revival. There is now a bagpiping club, a dozen music bands and about 100 pipers who play Belarussian bagpipes in Belarus and neighbouring countries like Lithuania, Latvia and western parts of Russia.

i) Italy

The zampogna bagpipe is native to central and southern Italy and Sicily. The two conical chanters, one for each hand, and two cylindrical drones are held in one large stock.4

j) Poland and the former Czechoslovakia

The Polish dudy and koziol are bellows-blown. The drone is either straight, or right-angled to hang down behind the player’s back. Both chanter and drone have large upturned bells. The dudy has six fingerholes and a thumb hole. The koziol includes a seventh hole. They can be traced in pictures back to the 14th century. The Bohemian dudy is similar to the Polish. Slovakia has bagpipes of this kind and are called gajdy and may be mouth-blown.15 The intervention of ethnomusicologists in Slovakia has had a tremendously positive effect on the revival of the bagpipe tradition today.8

k) Hungary and Romania

The Hungarian duda is generally bellows-blown. The chanter contains two parallel cylindrical bores. One is the chanter proper with six holes and a thumb hole, the other bore, the kontra, has one hole controlled by the little finger. The instrument has a normal bass drone. Traditional playing was revived in the 1980s. Romania has a similar instrument, the cimpoi15 but it is unknown if it is still played today.

l) The former Yugoslavia and Bulgaria

The bellows-blown gajde of the northeastern plains and parts of Serbia has a double-bore chanter with a large upturned bell. It has five holes, but the kontra bore also has a hole for the little finger. It also has a bass drone. The diple sa mjesinom or mih of Dalmatia and Bosnia is a simple mouth-blown instrument with double-bore chanter and no drone pipe. There are six holes to each bore.15 Although traditional gajde music in Serbia is disappearing, the intervention of ethnomusicologists gives hope for its survival.8

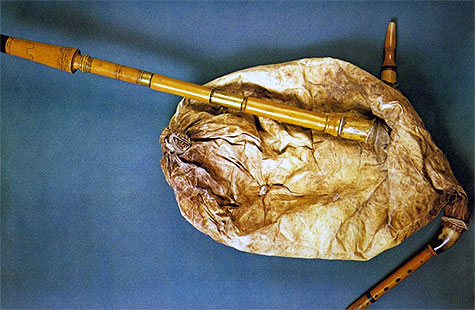

The Macedonian gajde has a single boxwood chanter with horn. There are seven holes and a thumb hole. The drone is also horn-mounted. The bagpipe is also very popular in Bulgaria, as are other types of gajde. Throughout these countries the gadje remains essential to wedding festivities and dances.15 The gaida (gajde) (Figure 2) is also played in northern Greece, Thrace and Albania.2

m) Bag-hornpipes

Bag-hornpipes do not have a drone pipe and possess a chanter composed of two parallel canes fixed together. Examples occur in the Greek islands (tsabouna see Figure 1), in northern Greece (played by Pontic Greeks), in northeastern Turkey (tulum), Armenia (parkapzuk), Georgia (gudastviri) and neighbouring regions of the Caucasus (chiboni).15 The tsabouna has recently gained a revival (note 2).14

Figure 2. Gaida bagpipe2

A reference to the tulum duduki by Evliya Chelebi [17th century] maybe the earliest reference to the instrument in a Turkish text.11 Bagpipes of the tsabouna type are found from a Greek manuscript of the 11th century and in wall-paintings in St Nicholas, near Kakopetria Cyprus as early as the14th century.2

3. The tsabouna (tulum) bagpipe

a) How the tsabouna is constructed2

The tsabouna (a bag-hornpipe) consists of a bag, a mouthpiece and a sound producing device, the double chanter (Figure 1) (note 3). The bag can be made from goatskin, kidskin or sheepskin and must be sound. So the throat of the animal cannot be cut or any other place as is usually the case when the animal has been slaughtered for meat. Initially, the skin is given a cursory cleaning with water after which the inner side of the skin is rubbed with salt. The skin is then rolled up and left for up to 15 days. Many add alum to the salt, which tightens the skin in addition to bleaching it and preserves its softness. Many Pontic Greeks from the Black Sea region treat the skins first with water and ashes and then with alum.

The hair of the skin is cut with scissors, allowing up to 1.5 cm of the hair to remain. The short bristles help stop the pores of the skin from stretching during playing and to hold moisture and saliva, which accumulates inside the bag from the player’s blowing. Thus, the moisture is prevented from damaging the reeds. Pipers who prefer to remove all the hair from the skin place the skin in slaked lime.

After the skin has dried with the hair-covered side folded inwards–the skin is then soaked in sea-water or kneaded on a round, smooth piece of wood, in order to be softened. The skin is rearranged so that the hairy side is outermost and the remaining legs, buttocks and tail are cut off and discarded. The nether region is closed, tightly bound with waxed string or a leather strap. Finally, the skin is turned completely inside out, so that the hair-covered side is on the inside. The neck is then pulled through one of the leg-holes and is firmly tied in the same manner as the nether part of the skin; it is then pulled inside once again.

The mouthpiece ranges from 6–18 cm in length and is made of cane, wood or bone. To the end of the tube, inside the bag, a round piece of leather can be bound which functions as a valve and prevents the escape of air from the bag.

The chanter consists of a grooved base into which are placed two cane pipes; these have single-beating reeds like a clarinet, and are positioned parallel to one another. This base terminates in a funnel-shaped bell. The grooved base is open on top and is closed at the rear, except the uppermost section containing the two reeds. The latter section is inside the bag; when the bag is squeezed, the resultant wind-pressure causes the reeds to vibrate. The overall length of the grooved base ranges from 20 to 30 cm.

Each pipe is made of two separate, interlocking sections of cane. The longer of the two sections – open at both ends – has the fingerholes. The second section, smaller in diameter, is open at one end only; the reed is located at the closed end. The two cylindrical tubes with the fingerholes are made first and have the same diameter bore.2 In the Aegean there are three types of tsabouna. The 5:5 type, with five fingerholes on both pipes; the 5:1 type, with five holes on the first pipe and one on the second and the 5:3 type, with five holes on the first pipe and three on the second.13 Once the cane pipes have been affixed to the grooved base, any spaces are sealed with wax.2 The small sections of the pipes, the reed-bearers range from 4 to 6 cm in length; their bores range from 0.7 to 1 cm in diameter.

The instrument depends on the proper functioning of these reeds. The reed is either up-cut, i.e. with the base of the reed adjacent to the knot of the cane or down-cut. The reed-bearers are fried in a small quantity of oil until they assume a slightly reddish tint. It is claimed this enhances their tone. As a result they are thoroughly dried out and are less affected by humidity or by the accumulation of the piper’s saliva in the bag. In addition, this process mitigates against natural decay. On some Greek Islands, the reed-bearers are treated with vinegar (rather that oil) when they are placed over fire in order to strengthen the cane. Pontic Greeks first boil the reeds in milk, which softens them before cutting.

Bagpipe makers use different methods to give the same note to the two reeds. The most common method is to wind a piece of thread around the root of the reed; this is then tied in a knot. Whenever the piper wishes to give the reed a higher-pitched voice, they push the thread closer towards its opening (the mouth); should they wish to produce a lower-pitched voice, they push the thread in the opposite direction. Pontic Greeks push the wax–which has been spread on the upper part of the grooved base to prevent the escape of wind from the instrument. This is done to cover either one of the roots of the two reeds of the bagpipe.

Once the two reeds have been matched in pitch, the reed-bearers are fitted to the long sections of the pipes with the fingerholes. Further adjustments may be made by changing the size of the fingerholes or by pushing broom-straw through the open end of the pipe until it reaches the particular fingerhole.2

Today in northeastern Turkey players usually buy their instruments from a specialist maker.12

b) Playing the tsabouna

Firstly, breathing correctly is an important part of playing. Pipers who breathe from the diaphragm rather than the chest are able to play for hours without tiring. The piper blows through the mouthpiece of the instrument while at the same time squeezing the bag thus forcing the air over the reeds of the two pipes. The playing of the bagpipe derives its character from the embellishments with which the piper continually adorns the melody. As for the piper, such ornamentation usually consists of grace notes–where one note of the melody is repeated rapidly after the next highest or lowest note has been played first.2

The tsabouna can be played under the right or left arm or on the chest, and the position of hands on the chanter can vary. While playing, the piper may sit, stand or even dance. Dancing is inseparably connected with playing the instrument.

Like all bagpipes, the tsabouna produces a continuous sound due to the constant flow of air through the reeds. The player cannot articulate the melody, because she/he does not have physical contact with the reeds, nor can the player easily play pauses or rests, staccato, or the same note twice in succession. In addition, the bagpipes do not have a range of dynamics [variation and contrast in force or intensity in music] (note 4).13

Traditional tunes are short and are made up of one or two bars and the range of the tulum is just six notes. The rhythms are complicated, fingered on one of the pipes that is played as an effective drone – even though each finger lies across both pipes, over a hole in each – by the way the player works the first and second joints of each finger. The music pours out a busy, intricate, two-parted polyphony, with gracings and drone effects that sound puzzling to a Western ear. The technique it calls for is subtle and complicated to master.12 Although it is possible to play many tunes with just a few notes on the tsabouna, modern tunes use notes outside the tsabouna’s range.10 This detracts from it being used in more ‘popular’ music.

The performance of the tsabouna is greatly affected by atmospheric humidity as well as the amount of the player’s saliva and air inside the bag. The same problem arises when the bagpipe has been played continuously for several hours; the reeds become saturated and heavy, and the tone of the instrument is lowered.2

Although the tsabouna is primarily a solo instrument it is also played in conjunction with the toubaki (small drum), daouli (drum) (note 5), the lyra (fiddle) and the lute.2

c) Where is the tsabouna (tulum) played?

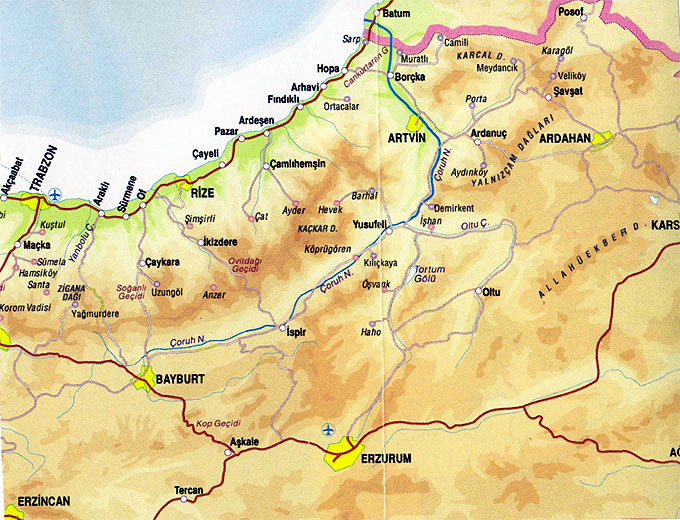

In Turkey, the tulum is found in the northeastern provinces adjacent to the Black Sea (Figure 3). In the past, tulums were recorded from Turkish provinces of Choruh (Artvin), Erzurum, Gumushane (Bayburt), Mush, Rize and at high altitudes in Trabzon. The tulum was found in Rize at an altitude above that of Hemshin (1,000–1,500 metres). It was known as the instrument of the semi-migrant, stock-raising population of the northeastern provinces of Anatolia (Figure 3). In the Artvin area, the general term for the commonest type of dance is horon. The dances are performed as closed or half-circles, with the piper in the centre calling the movements.11

In Turkey today, the tulum tradition survives in the hills surrounding Rize, in the villages of the Tatos range (the watershed between the provinces of Rize and Erzurum) and in the Artvin region to the east, among the Laz and the Hemshin peoples in particular. Today, it is estimated that there are fewer than 300 active tulum players in the Rize region. However in Turkey, interest in playing and listening to the tulum and dancing to it (horon) is increasing. In the Black Sea region, the tulum is an integral part of the culture and manifest in wedding celebrations (as the instrument which leads the dancing), folk festivals and concerts. It clearly has a future.12

Figure 3. Northeast corner of Turkey’s Black Sea region (scale 1cm = 20 km)9

The revival in interest in tulum playing commenced with the Karadeniz (Black Sea) rock recordings of Zuğashi Berepe and the rock band Grup Yorum and the pre-eminent tulum recording artist in Turkey, Mahmut Turan (who is ethnically Hemshin), among many others (personal communication, Dr Eliot Bates, July 2014). The musical traditions of the east Black Sea region are also being preserved through the efforts of kemenche and tulum player and Laz vocalist Birol Topaloglu.

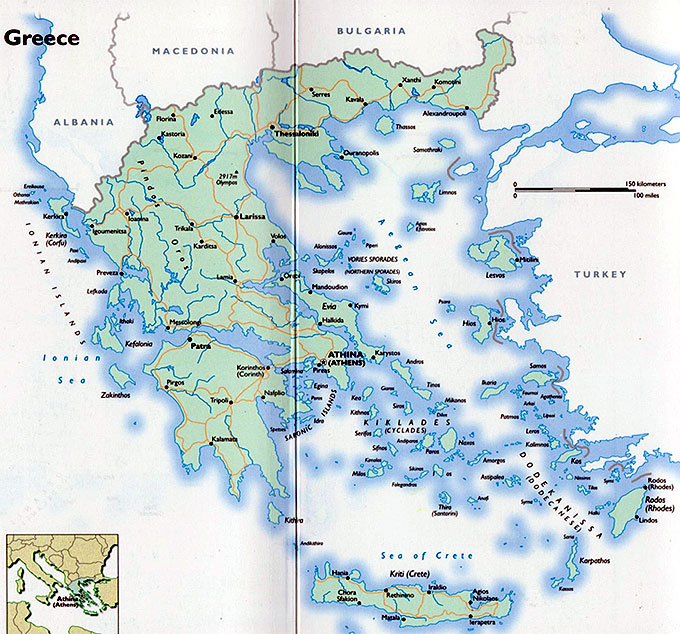

In Greece, the tsabouna belongs to local folk music culture of about 20 Greek Islands14 such as Andros, Chios, Crete, Euboea, Kalymnos, Karpathos, Kephalonia, Mykonos, Naxos, Patmos, Samos, Sifnos, Symi, Syros, Tinos and in northern Greece and Athens where Pontic Greeks from the Black Sea have settled (note 6) (Figure 4). In the Greek Islands it has long been played to accompany dancing and singing at weddings, baptisms and village festivities.2

Figure 4. Map of Greece7

In the 1970s, among the Pontic Greeks in northern Greece, the kemenche (Pontic lyra) made up approximately 70% of the entire musical practice. The tsabouna made up to 15% (previously this figure was higher). There were few individual recordings of the tsabouna (note 7).1 A recent resurgence in the playing and listening to the tsabouna has occurred epitomised by Yannis Pantazis on the island of Santorini (note 2). The tsabouna is played at festivals and dances by the Pontic Greeks in northern Greece and in Athens.

4. Resurgence and concluding remarks

What should we do with past musical traditions? Do we need to keep them in their original form and place them in the musical museum? Or should we develop and change them, or should we just abandon them?8

In Turkey, the tulum is a very popular musical instrument for the Laz and Hemshin people of the northeastern corner of Turkey. The performances and recordings of Karadeniz rock performers, Mahmut Turan and Birol Topaloglu are (amongst others) responsible for assisting in the resurgence in tulum playing.

In Greece, since around 2000, while the tsabouna tradition seemed close to its end, a revival movement has appeared. One of these revivalists is Ioannis Pantazis who makes, plays and teaches the instrument on the Greek Island of Santorini.

Many young people, in both Greece and Turkey, are interested in learning the tsabouna and this is likely to promote the revival. But the way that the music is conceptualised has changed. The younger generation tends to follow music through recordings, with compositions which have a fixed beginning, end and duration. This perception is contrary to the traditional playing of the instrument, where tunes are ‘regenerated’ whenever they are played. The older generation of tsabouna players still think this way and this comprises the ‘backbone’ of Aegean Island instrumental music.13

The tsabouna (tulum)is a much loved musical instrument played in Greece and parts of Turkey and many other countries where the Greek and Turkish Black Sea diaspora now reside. We must not abandon it! We need more studies on the status of playing the bagpipes and other folk instruments in Greece and Turkey and what the future may hold.

May we encourage the playing, listening and dancing to folk music using such traditional instruments as the tsabouna, kemenche and daouli. Such a commitment is a means of expressing joy, a reflection of our society, history and a means for building an understanding and appreciation of our cultures.

5. Notes

Note 1: The music of the Black Sea coastal area of northeastern Turkey (the Pontos), from at least the Trabzon area to the Georgian border, is dominated by the kemenche fiddle and the tulum bagpipe which are not commonly found in other parts of Anatolia. (See the author’s article on the kemenche (Pontic lyra) at:

www.pontosworld.com/index.php/music/iistruments/326-the-kemenche-2). The instruments are closely connected to the Laz and Hemshin people who live there. This music was also played by the Pontic Greeks who lived there. For simplicity in this article I have assumed that the tsabouna (tulum) played by Pontic Greeks and the tsabouna played in the Greek Islands (as they have a double chanter and no drone pipe) are the same instrument. This is not strictly true as they have some small differences which affect how they are played (personal communication, Dr Haris Sarris, August 2014).

Note 2: Ioannis Pantazis learnt to play and make tsabounas from the shepherds from the Greek Island of Naxos. Ioannis lives on Santorini where he makes and teaches the tsabouna and performs regular concerts.

The tsabouna's traditional repertoire consists of the folk dances particular to each island, local songs, and music for religious festivals and weddings. It used to have a central role in every musical event of the islands – but in the last decades its traditional use was confined to small gatherings and informal celebrations far from the central public areas. However, interest in the tsabouna is growing, with new musicians, a new audience, a new repertoire along with an old one allowing the tsabouna to remain alive (www.laponta.gr).

Note 3: In 1976 the lavishly illustrated landmark book, Greek popular musical instruments by Mr Fivos Anoyanakis was published in Greek. It was published in English in 1979 and reprinted without updates, in 1991. Thus his excellent research is accurate up to 1976.

Note 4: Refer to the excellent work of Sarris (2007) for more detailed description and on how the tsabouna player deals with these limitations.

Note 5: The daouli is a double sided drum (see the author’s article at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/music/iistruments/327-the-daouli-drum-2).

Note 6: The tsabouna was once the most important instrument in the Aegean region. It is still played in most of the Cyclades and Dodecanese Islands. But in 2007 it was reported to have disappeared from Kassos, Rhodes, Symi, Kastellorizo, Halki and Tilos.10 It has made a recent comeback on Santorini.

Note 7: As ‘an’ example of how common the tsabouna is played on Pontic CDs – on the Greek Dora Stratou Dance Theatre and Dance Company 199? produced music CD, Twenty Pontic dances and songs, a tsabouna is played on five of the 20 songs. In contrast, the kemenche is played on 17 songs.

6. Acknowledgements

The author warmly thanks Dr Eliot Bates and Dr Haris Sarris (whose works are recommended to the reader) and my ever-inquisitive friend Russell McCaskie for their invaluable corrections and comments to a draft of this article. All short-comings in the current article remain with the author.

7. References

1. Ahrens, C 1973, ‘Polyphony in touloum playing by the Pontic Greeks’, Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council, vol. 5, pp. 122–31.

2. Anoyanakis, F 1991, Greek popular musical instruments, 2nd edition, Melissa Publishing House, Athens.

3. Baines, A 1992, ‘Bagpipe’, The Oxford Companion to Musical Instruments, pp. 13–17, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

4. Baines, A 1995, Bagpipe (3rd edition), Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, Occasional Papers on Technology No. 9, Oxford.

5. Baryshnikau, E 2014, ‘Bagpipes of Belarus: history, revival, perspectives’, abstract, second International Bagpipe Conference, 8 March 2014, London, organised by the International Bagpipe Organisation.

6. Collinson, F 1975, The bagpipe: the history of a musical instrument, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

7. Gerrard, M 2007, National Geographic Traveller: Greece, (2nd edition) National Geographic, Washington, D.C.

8. Jakovljević RS 2012, Marginality and cultural identities: locating the bagpipe music of Serbia, PhD thesis, Department of Music, University of Durham, England.

9. Nişanyan, S & Nişanyan, M 2001, Black Sea: A traveller’s handbook for northern Turkey, Infognomon Publishing, Athens.

10. Paterson, M 2007, ‘Naxos’ pipes face uncertain future: the tsambouna of the Cyclades’, Piping Today, no. 27, pp. 30–36.

11. Picken, L 1975, Folk musical instruments of Turkey, Oxford University Press, London.

12. Piping Today, 2013, ‘Tulum lives on in its Black Sea heartland: the bagpipe of Anatolia’, Piping Today, no. 62(?), pp. 26–29.

13 Sarris, H 2007, ‘The influence of the tsaboúna bagpipe on the lira and violin’, The Galpin Society Journal, vol. 60, pp. 167–80, 116–17.

14. Schinas, GP 2014, ‘Tsambouna tradition and revival in Greece’, (abstract), second International Bagpipe Conference, 8 March 2014, London, organised by the International Bagpipe Organisation.

15. The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, 1984, vol. 1, ‘Bagpipe’, Stanley Sadie (ed), pp. 99–111.