By George Topalidis | The displacement of Syrian refugees to European shores over the past five years has led US public opinion to revisit themes from the academic discourse about immigration. Isolationism, nativism, and restrictionism permeate modern public opinion and in the process transport its audience through a time warp to the early-twentieth century.

By George Topalidis | The displacement of Syrian refugees to European shores over the past five years has led US public opinion to revisit themes from the academic discourse about immigration. Isolationism, nativism, and restrictionism permeate modern public opinion and in the process transport its audience through a time warp to the early-twentieth century.

These themes reverberate in the rhetoric of contemporary US public figures. They dehumanize refugees and thereby facilitate future immigration restrictions against them.

A hundred years ago, this type of public rhetoric resulted in the drafting of the most restrictive immigration legislation in US history: the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921. The act’s main provision established quotas based on a three percent immigrant admission rate per annum, itself derived from the 1910 US Census figures of each US resident’s country of origin. When exhausted in a given year, the quotas restricted immigration and enacted the contemporaneous deportation procedure. This provision expanded immigrant categories of the 1917 Immigration Restriction Act.

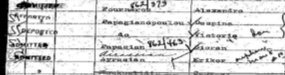

The aim of this essay is to raise public awareness about effects that such legislation had on some of the weakest targets of the time, ninety refugees from Smyrna. Port agencies and their staff were the first forms of officialdom that the refugees encountered. The state’s vetting system generated ship manifests, which recorded their arrival, screening, admission, quarantine, or in this case deportation procedures. Border agents labeled cases of deportation on ship manifests by applying a “Deported” stamp next to the names of the deportees.

"Deported"

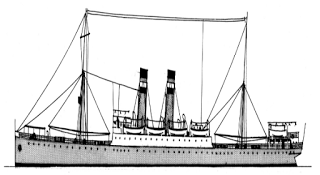

The ship manifest of the S.S. Acropolis problematized the Smyrna refugees’ story as conveyed by contemporary press reports. The first issue contested was the actual number of refugees from Smyrna. Here, the newspaper articles provided nebulous and contradictory information. The first report by the New York Times cited ninety refugees with transitory immigration status.A month later, follow-up reports decreased that initial number to seventy, comprising fifty-one Armenian and nineteen Greeks. The Greek-American press contradicted that figure by noting ninety “primarily” Armenian refugees; without enumerating the Greeks.

The SS Acropolis

The Ellis Island manifests provide an even lower number: a total of forty-four passengers from the S.S. Acropolis were deported. Of those, eleven were returned to Greece aboard of the S.S. Madonna, which departed on February 9, 1923. None of the eleven deportees were from Smyrna; four were Greeks from Tenedos, modern Bozcaada, and one from Kaisareia, modern Kayseri. There were also fifteen Armenians: nine were from Nikomēdeia, modern Ismid, and five from Aintob, modern Gaziantep, Turkey. The remaining thirty-three were deported on various dates and with various ships. Therefore, the seventy Smyrna refugees were not former passengers of the Acropolis. This is an important fact for the reader to keep in mind as the refugees’ story unfolds.