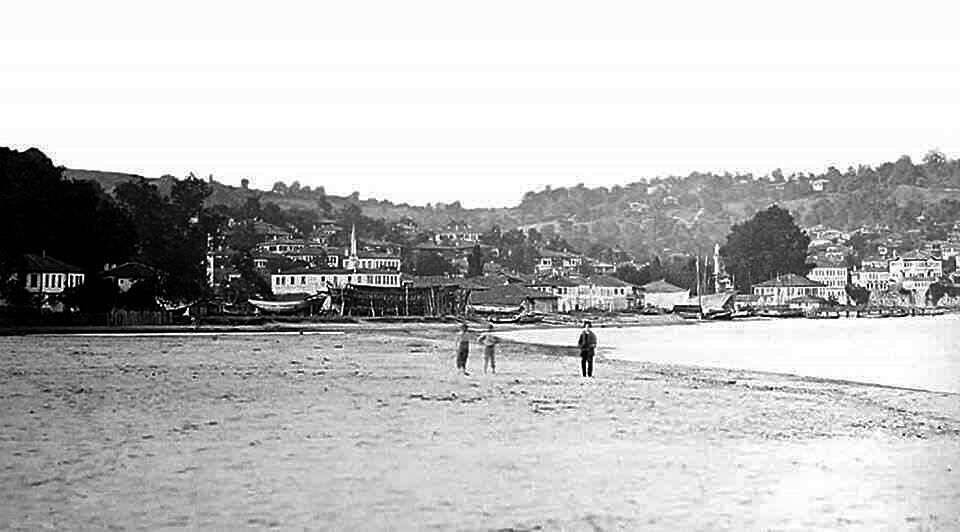

Plate 1: Unye, 1875. Photo: Dmitri Ivanovich Yermakov

The History of Unye (Oinaion), Pontos

Sam Topalidis 2025

(Pontic Historian and Ethnologist)

Introduction

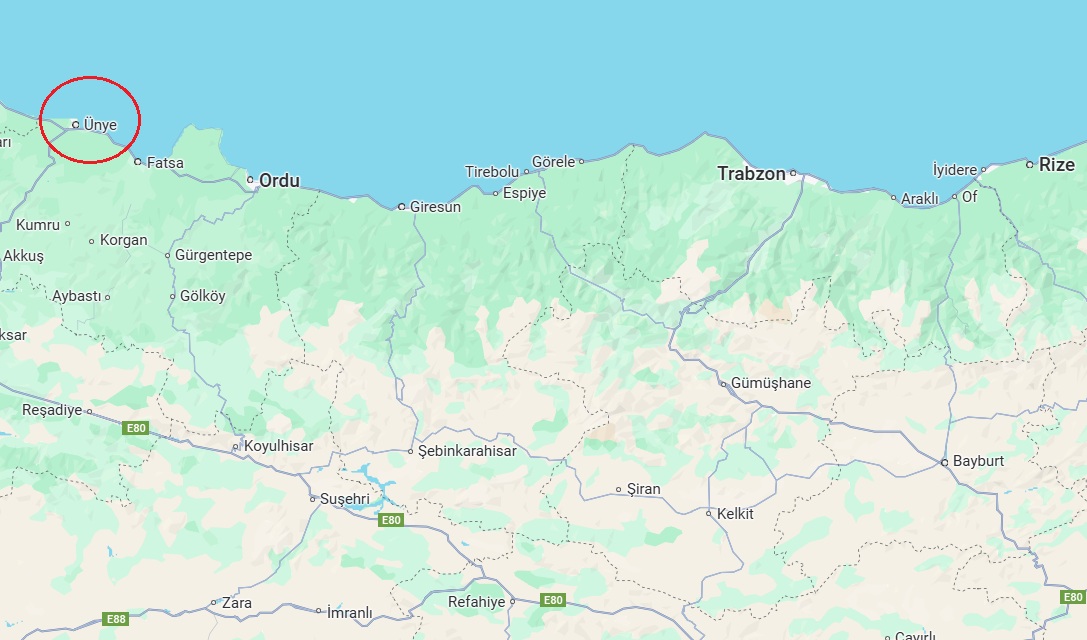

Unye (classical and medieval Oinaion) is a coastal town located on the southern Black Sea coast (Fig. 1; Plates 1–2) of north-east Türkiye (Pontos). The town is around 92 km east of Samsun and 240 km west of Trabzon. There is no definitive explanation for how the town acquired its name. The town has a rich history and is known for its stunning coastline with beautiful beaches surrounded by lush green forests (trackstick.com/unye-turkey/).

Fig. 1: Map of northern Türkiye (Sinop to Trabzon = 400 km, Source

Plate 2: Unye 2018 Source

History

At Tozkoparan, 4 km east of the Unye town centre, a settlement has been discovered dating to the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic periods (40,000–12/10,000 BC). It is the only settlement with finds for the Palaeolithic period on the north-east coast of Türkiye. Then the settlement was re-established in Late Chalcolithic [4300–2950 BC]1 and Early Bronze Age (Oy (2018); Yiğitpaşa and Yağci (2024)). Unye was colonised by Greeks in 5th–4th century BC (at the earliest), but there would have been indigenous Anatolians already living at the site.

When the army of Alexander the Great (336–323 BC) defeated the Persians in Anatolia, the Greeks did not march north to conquer the Black Sea coast although these areas eventually accepted his authority (Şerifoğlu and Bakan 2015). In 302 BC, Mithradates I of Persian descent, established the kingdom of Pontos (Roller 2020). Mithradates and kings from the same family ruled over the area from Heraclea (west of Sinope) east to Trabzon on the Black Sea coast until the reign of Mithradates VI who was defeated by the Romans in 64 BC (Erciyas 2001). The kingdom of Mithradates VI, which encompassed Pontos and other areas around the Black Sea and parts of Anatolia, was eventually absorbed within the Roman empire in the 60s AD (Roller 2020). It then became part of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire.

In 1157, Medieval Oinaion (modern Unye) may have been in Danişmendid2 hands, but the Byzantines recaptured it in 1175. In 1204, it was ruled by Alexios and David Komnenos at the foundation of the small independent Byzantine Komnenos kingdom of Trebizond (1204–1461). In 1347, Unye was lost to the Turkmen emir. In 1358, Unye was restored (if not earlier) to the Trebizond kingdom. In 1404, Clavijo (Castilian traveller and writer) noted that except for 300 Turks, the population of Unye was mostly Pontic Greek. It may have passed into [Ottoman] Turk hands between 1404 and 1445 (Bryer and Winfield 1985:101).

Unye flourished as the port of Niksar (Fig. 1), particularly in the early 19th century. However, a fire in 1839 nearly destroyed Unye and it then lapsed into something of a backwater. At that time, Pontic Greeks formed most of the population but seven years later, the town was two-thirds Turkish. Perhaps some of the Unye’s Pontic Greek traders relocated to Samsun after the 1839 fire (Bryer and Winfield 1985:102). There were quarries3 and iron, silver lead and manganese mines in the district (unyekent.com/haber/1864-68-yillarinda-unye-vilayet-olmustu-17449.html).

Kourkouletza was one of the six wealthy Greek neighbourhoods in Unye and within the Greek neighbourhoods, the Greek church dedicated to the Dormition of Our Lady was still standing in 1930 (Ioannidou 2016:29, 49).

Population

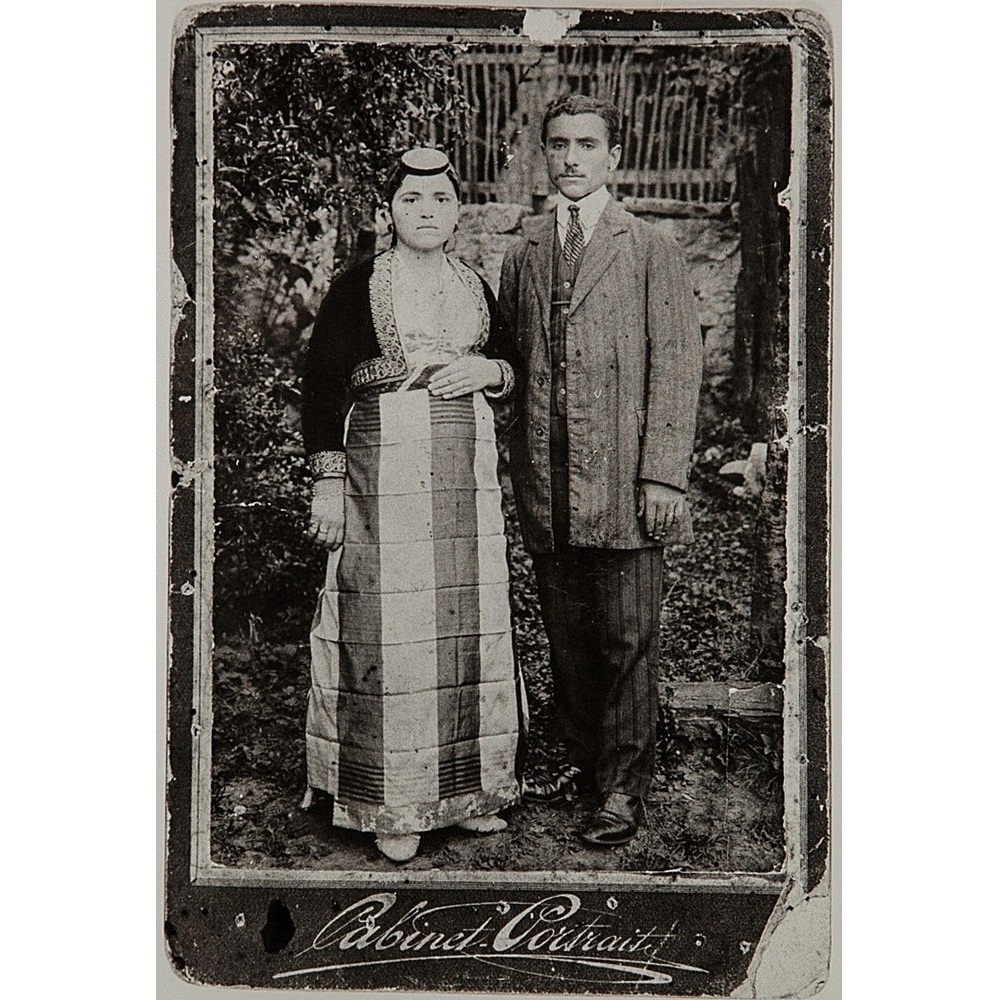

Towards the end of the 19th century, Unye’s population was around 10,000 [and comprised mostly Muslims] (www.unye-gov-tr.translate.goog/unyenin-tarihi?_x_tr_sch=http&_x_tr_sl=tr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc). In 1902, there were about 4,000 Pontic Greeks (Plate 3). In 1910–1912, there were 6,200 Greeks in Unye county. In 1914, the Pontic Greek population of the town dropped, apparently due to migration, to around 2,500 Greeks (Alexandris 1999; Lazaridis 1988). The Greeks of the settlement spoke Greek and the Romeyka Greek dialect.4 In 1914, 700 Armenians also lived in Unye with [apparently] 7,700 Armenians living in the Unye county (Kévorkian 2011:492). Until 1914 the relations between Muslims and Christians of Unye were very good (www.ehw.gr/asiaminor/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=9352).

Churches

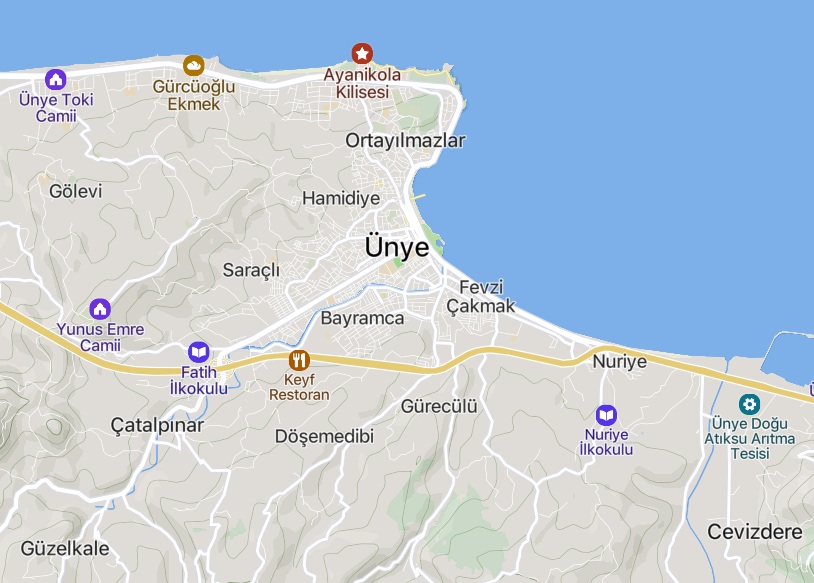

In 1813–1814, there were many mosques, two Greek and one Armenian church. The medieval Greek chapel of St Nicholas was located 3 km west of the town centre (at Ayanikola, Fig. 2). It was a single apsed chapel about 2.5 m by 3.4 m. Sadly, any remains were destroyed by 1970 by Turkish treasure hunters (Bryer and Winfield 1985:103).

In 1914, there were two Greek parish churches in the town: St Nicholas and the Holy Trinity Church (https://virtual-genocide-memorial.de/region/page/36/). St Nicholas was in ruins by 1930 (Plate 4) and today, only its foundations remain (Plate 5).

The Armenian quarter was next to the Pontic Greek quarters on the north-west side of the town. The Armenians concentrated around the Aramian school and Surb Minas church (built in 1831 and rebuilt in 1840) (Kertmenjian 2009:208).

Plate 3: Elftheriadis couple, Unye 1892 Source

Today, the only former Greek Orthodox church in Unye is located in the Central Ortayılmazlar neighbourhood (Plate 6). Its original name is unknown [but it could be the Holy Trinity church] with three apses and was built in the second half of the 19th century. After the Exchange of Populations in 1923, it fell into disrepair. In 1937–1950, it was used as a power plant to generate electricity. In the 1960s, it was used for weddings, theatre and other performances. In the 1980s, it was mostly used as a warehouse and in 2015, it was used as a wedding hall and it now serves as a Culture and Art Centre (www.unye.bel.tr/sehir-rehberi/yali-kilisesi/ www.sekizgenacademy.com/journals/index.php/inda/article/view/50/30).

Fig. 2 Unye, northern Türkiye Source

Plate 4: St Nicholas church west of Unye town centre (1930, Öztürk 2011:508

Plate 5: The St Nicholas church site in Unye today Source

Plate 6: Former Greek church (possibly the Holy Trinity) Unye, 2023 Source

Greek Schools

In 1866, a small American Protestant mission was established at Unye.5 In 1900, its little congregation was led by a Greek physician, while the school students were being taught by his Armenian wife (The Missionary Herald April 1900:157).

In 1870, there was one Greek Orthodox school with 330 students. By 1896, Unye had two Greek Orthodox schools with 270 students and six teachers (Lazaridis 1988:53, 59).

Philanthropic Clubs

There were several clubs established by the Pontic Greek Orthodox community. In 1890, the Reading Room of Unye ‘Philadelphia’ was founded. It supported the Greek Orthodox schools of Unye and the surrounding villages, to find work for the poor and to educate Greek Orthodox residents. An association called ‘Patris’ was founded in 1909 to support the schools and educate the Orthodox residents. A third club, ‘O Evaggelismos’ was formed to assist the community schools (www.ehw.gr/asiaminor/Forms/fLemmaBody.aspx?lemmaid=9352).

Genocide

On the eve of the 1915 Armenian deportation, 25 Armenian notables from Unye county were imprisoned and shot. Then in 1915, the Armenian population was forcibly deported in four caravans although approximately 150 Armenians fled to the mountains where they survived for several years. Later, under the Kemalist regime, they were forced to leave for Georgia (Kévorkian 2011:492–493).

After the Russians invaded north-eastern Anatolia in 1916, during World War I, the Ottoman Turks responded by forcibly moving Pontic Greeks around the Anatolian Black Sea without adequate provisions or shelter into the interior of Anatolia where many perished. The Russian invasion also created a mass-movement of at least tens of thousands of Muslims away from the military fronts.

In 1916, Ottoman Turk forces took 500 Pontic Greeks hostage [from the Unye area] and attacked Greek guerrillas at the village of Keris. After the guerrillas escaped, Ottoman forces killed the hostages and burnt their villages (virtual-genocide-memorial.de/region/page/36/).

According to the Trabzon Greek newspaper, Epohi [Time], a deportation from Unye took place in January 1917. They included approximately 60 Greek men who were among the most influential in the town. They were forced to walk to Amasya (Fig. 1) where half died in the first 10 days (Ioannidou 2016). In late May, Russians ships shelled Unye sinking 20 sailing ships (Greger 1972). According to the Greek Patriarchate (1919), there was another Pontic Greek deportation in July 1917.6 Many Christians took shelter in the woods, with 300 of them escaping to Trabzon [occupied by the Russian army].

According to a 1919 report by British Lieutenant Perring, the Christians who returned to Unye after World War I were not given back their property. This resulted in 300 Christians needing to be fed daily by the relief fund (Fotiadis 2019).

In early June 1921, (during the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) in western Anatolia) a kingdom of Greece warship bombed Inebolu (west of Sinope) after which Pontic Greek males aged between 15 and 50 years located further east on the Black Sea were deported to the interior (Mango 2002). On 16 June, 101 Greek men from Unye were marched south-west to Tokat (Hionides 1996). In September 1921 the bands of Mustafa Kemal massacred most of the Christian males of Unye. Some men escaped and took refuge in the mountains. The Turks ordered the deportation of the remaining boys and women (Central Council of Pontus 1922).

In September 1922, after the Turks had recaptured Smyrna from the occupying kingdom of Greece forces, Anatolian Greeks were being forced to leave for Greece. As a result of the Lausanne Convention, signed by Greece and Turkey in January 1923, those Christian Greeks who had not already left Turkey were forced to leave.

In April 1923, all the remaining Christian Greeks in Unye had to leave for Greece. One ship took 362 passengers from Unye (Ioannidou 2016).

Unye Today

Unye’s estimated population is 97,600 people (2022) (worldpopulationreview.com/cities/turkey/unye). Today, the main industries in Ünye include: agriculture, fishing, tourism, manufacturing of textiles and food processing. Hazelnut production is a significant agricultural activity in the region. The town’s port also supports the transportation of goods for trade purposes (trackstick.com/unye-turkey/).

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Michael Bennett and Russell McCaskie and for their comments to an earlier draft.

References

1. Words within square brackets ‘[ ]’ are the author’s words.

2. Danişmendids were Turkmen who arrived in Anatolia with the Seljuk Turks.

3. Unye limestone was used in the construction of the Byzantine St Sophia church in Trabzon (Bryer et al. 1972–1973).

4. See the author’s article on Romeyka at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/892-romeyka-an-endangered-greek-dialect

5. See the author’s article on the American Protestant Missions in Pontos at: www.pontosworld.com/index.php/history/sam-topalidis/823-american-protestant-missions-in-pontos

6. See ‘Pontic Greek family histories: Sophie Kiriakidis’ in Topalidis (2019:119–126). Book available at: www.afoikyriakidi.gr/en/books/pontus-history/history-and-culture-of-greeks-from-pontos-black-sea/

Sources

Alexandris A (1999) ‘The Greek census of Anatolia and Thrace (1910–1912): a contribution to Ottoman historical demography’ in Gondicas D and Issawi C (eds) (1999):45–76 Ottoman Greeks in the age of nationalism: politics, economy, and society in the nineteenth century, The Darwin Press Inc, New Jersey, USA.

Bryer A and Winfield D (1985) The Byzantine monuments and topography of the Pontos, I, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, Harvard University, Washington DC.

Bryer AAMB, Isaac J and Winfield DC (1972–1973) ‘Nineteenth-century monuments in the city and vilayet of Trebizond: architectural and historical notes Part 4’, Archeion Pontou (Archives of Pontos) 29:128–310.

Central Council of Pontus (1992) Black book: the tragedy of Pontus 1914–1922, Central Council of Pontus, Athens.

Erciyas DBA (2001) ‘Studies in the archaeology of Hellenistic Pontus: the settlements, monuments, and coinage of Mithradates VI and his predecessors’, PhD thesis, University of Cincinnati, USA.

Fotiadis KE (2019) The genocide of the Pontian Greeks, (unknown translator from Greek into English), KE Fotiadis, (unknown place of publication).

Greek Patriarchate (1919) Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey 1914-1918, (Greek Patriarchate in Constantinople), Hesperia Press, London.

Greger R (1972) Russian fleet, 1914–1917, (trans into English by Gearing J) Alan, London.

Hionides C (1996) The Greek Pontians of the Black Sea, C Hionides, Boston.

Ioannidou T (2016) The holocaust of the Pontian Greeks: still an open wound, Theodora Ioannidou, Place of Publication not stated.

Kertmenjian D (2009) ‘Armenian city quarters and architectural legacy of the Pontus’,:189–215, in Hovannisian RG (ed) (2009) Armenian Pontus: the Trebizond-Black Sea communities, Mazda Publishers Inc, Costa Mesa, California.

Kévorkian R (2011) The Armenian genocide: a complete history, IB Taurus, London.

Lazaridis D (1988) Στατιστικοι πινακες της εκπαιδεύσεως των Eλληνων στον Ποντο 1821–1922 (in Greek), [Statistical list of Greek schools in the Pontos 1821–1922], Archeion Pontou [Archives of Pontos] 16, Epitropi Pontiakon Meleton, [The Committee for Pontic Studies] Athens.

Mango A (2002) Atatürk: The biography of the founder of modern Turkey, The Overlook Press, New York.

Oy H (2018) ‘The prehistoric settlement at Tozkoparan (Unye-Ordu-Turkey)’, Karadeniz Araştirmalari Merkezi, 57:33–42.

Öztürk O (2011) Pontus: Antikçağ’dan Günümüze Karadeniz’in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi (in Turkish), [Pontos: the ethnic and political history of the Black Sea from antiquity to the present], Genesis Kitap, Ankara.

Roller DW (2020) Empire of the Black Sea: the rise and fall of the Mithridatic world, Oxford University Press, New York.

Şerifoğlu TE and Bakan C (2015) ‘The Cide-Şenpazar region during the Hellenistic period (325/300–1 BC)’, in Düring BS and Glatz C (eds) (2015), Kinetic landscapes: the Cide archaeological project: surveying the Turkish western Black Sea region,:246–259, De Gruyter Open, Warsaw, Poland.

The Missionary Herald (April 1900) XCVI(4), American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Boston.

Topalidis S (2019) History and culture of Greeks from Pontos Black Sea, Kyriakidis Bros, Thessaloniki.

Yiğitpaşa D and Yağci A (2024) ‘Life activities in the region in the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Bronze ages in the light of the stone tools found in the Ordu and Sinop museum’, Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology, 11(1):41–57.